“Timbuktu is not a place!” A know-it-all friend or cousin back in school must have yelled at least once while playing one of those innocuous name-place-animal-thing word games. In the Oxford English Dictionary, as well as in popular imagination, Timbuktu is a "remote or an extremely distant place". English writer and poet D.H. Lawrence once wrote in 1930: And the world it didn't give a hoot/ If his blood was British or Timbuctoot.

Back in 2012, when the historic city of Timbuktu in northern Mali fell to jihadists, who set ablaze two important libraries holding thousands of ancient manuscripts on Islamic culture, people reacted on Twitter: "Omg! Just found out Timbuktu is a real place!" Some of those manuscripts, promptly rescued, have now reached New Delhi's National Museum, for an exhibition titled "Taj Mahal Meets Timbuktu".

India is synonymous with Taj Mahal, a monument to eternal love; in the same way, Mali is inseparable from Timbuktu, an important centre of scholarship and trans-Saharan gold and salt trade from the 13th to 17th century. However, it now lies battered and desolate. Timbuktu seamlessly converged West African and Arab influences with Islam as the binding agent, and even to this day the city is peopled with an eclectic mix of Tuaregs, Songhay, Soninke, Dioula, Fulani and Arabs.

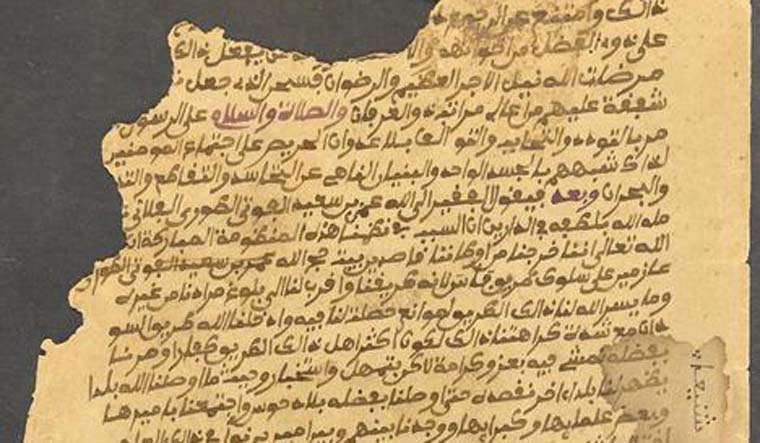

At the exhibition, 25 sets of fragile parchments are inked with exquisite calligraphy in black, red and green. Their themes are wide-ranging: from Quranic science and matters of jurisprudence to agriculture, astronomy and social life. Be it a 19th century treatise in Saharan calligraphy on good social behaviour and moral values to descriptive illustrations of the solar system, a 14th century manuscript on the virtues of work to a 17th century travel account of Egypt, Iraq and Europe in Sudanese calligraphy, an Arabic manuscript on sexology and intimate life to a scientific treatise on mathematical operations, the exhibition delicately encapsulates the golden age of Timbuktu in a series of small, rectangular glass vitrines. Situated in one corner of the Ajanta Hall at the National Museum, the sparse, no-frills display quietly dazzles with an element of mystery.

In 2012, when Islamist rebels seized control of Timbuktu, the manuscripts rescue operation undertaken by Dr Abdel Kader Haidara, who owns a private library in the city, is a story by itself. The precious documents were hidden in metal boxes and secretly evacuated in "cars, carts and canoes", over thousands of kilometers through Mali. "Some 95 percent of all the manuscripts are now in Bamako, the capital of Mali. Timbuktu is a very unsafe place now. There is no security for these documents there," says Traore Banzoumana from a Bamako-based non-profit which has undertaken the preservation and restoration of the manuscripts by signing an agreement with the government of the Republic of Mali.

The exhibition, which is on display till June 6, will travel to Canada and Turkey next.