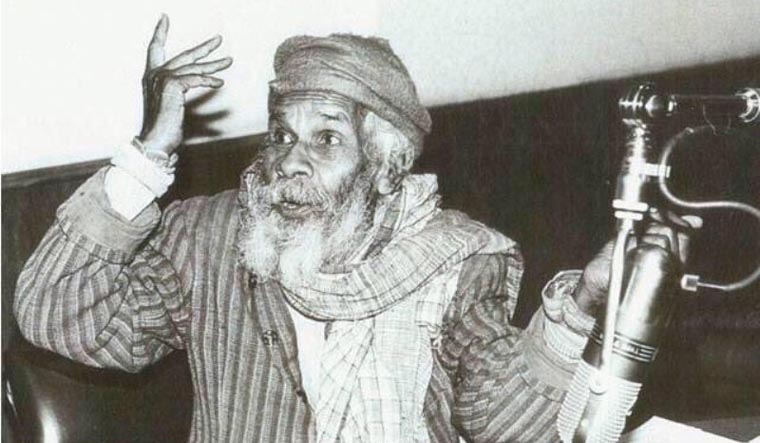

Baba Nagarjun was one of the most versatile poets that Hindi has ever had. He is often placed on the same pedestal as Kabir, for the level of intimacy that his poems are infused with. If seen broadly, the entire Hindi poetry tradition comes alive in Nagarjun’s works. From romance and politics to mythology and revolution, the people’s poet has touched it all.

His poet-personality has the qualities of classical poets like Kalidas and Vidyapati. His practical pursuit was laced with multi-faceted philosophy of awareness, Buddhism, Marxism, and above all, the problems of his time. A poet with such a wide approach, he has also established a folk identity for himself by his direct engagement with the concerns and struggles of rural class and a deepened understanding of Indian culture.

Nagarjun used his inner ‘traveller’ to understand the Indian psyche and his subject in a holistic and true form. In addition to Maithili, Hindi and Sanskrit, his knowledge of various languages such as Pali, Prakrit, Bangla, Sinhalese and Tibetan has also been helpful for this purpose. His dynamic, active, and committed life reflects in his poetic endeavours.

Nagarjun has always kept the sense of his poems real and simple. His use of urgency in his works has drawn a fair share of criticism. His critics might have overlooked the fact that he used urgency as the biggest weapon of democracy in his poems. The impact made by many of his famous poems such as 'Indu ji, Indu ji kya hua apko' and 'Aao Rani, hum dhoenge palki', are testimonies to this fact.

His poems of love and nature connect with the Indian consciousness in the same way as his political ones. Baba Nagarjun, in many ways, was both a simple and an aggressive poet.

One among many of Nagarjun’s poems that needs special mention is Kalidas. Empathy, a quality of a great poet, stands out in this piece.

Kalidas sach sach batlana

Shiv ji ki teesri ankh se

Nikli hui mahajwala se

Ghrit mishrit sukhi samidha sam

Kamdev jab bhasm ho gaya

Rati ka krindan sun ansu se

Tumne hi to drig dhoye the

Kalidas sach sach batlana

Rati royi ya tum roye the

Nagarjun poses a question to Kalidas, referring to his monumental work Kumarasambhava. When Kamdeva was reduced to ashes by Shiva, and Rati, the wife of Kamdeva, wept inconsolably, Kalidas was the one to wipe off her tears, says Nagarjun. “O Kalidas, was it Rati who wept or was it you?” asks Nagarjun.

His The Famine and After remains one of the greatest poem on the pangs of hunger and tragedy. He has described a situation familiar to the marginalised, precisely with lines such as:

Kai dinon tak chulha roya, chakki rahi udaas

Kai dinon tak kani kutiya soyi uske paas

Nagarjun’s singularity and aggressiveness is much more relevant today. He has reached a place where other poets dare to set foot. The sad part, however, is that he has not received his due share like many others.