Disinviting international authors and artists, producing culturally provocative works, is often employed as a tool of censorship. Last-minute visa cancellation is one such method.

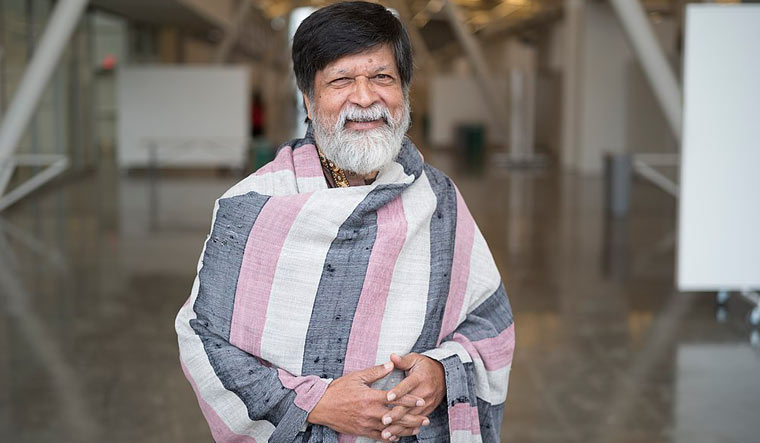

While most invitees to concerts, talks and festivals are forced to backtrack when such measures are taken, a few remain undeterred. So, when renowned Bangladeshi photojournalist and activist Shahidul Alam was allegedly denied an India visa to attend a panel discussion in New Delhi on September 13 , he made his presentation via Skype and even managed to participate in a brief Q&A despite a patchy internet connection.

Alam, who was Time magazine's 'Person of the Year' photographer in 2018, set up Drik Gallery, Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Chobi Mela International Photography Festival and Majority World in Bangladesh. His works have been showcased at Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Centre Georges Pompidou, Royal Albert Hall, Tate Modern and Museum of Contemporary Arts Tehran. During the 2018 student protests in Bangladesh, the award-winning photographer was jailed for more than 100 days for vocalising his concerns against the government on Facebook and Al-Jazeera Television. His arrest had triggered international protests with even Nobel laureates demanding his release. Alam has also been critical of the rise in majoritarian politics in India.

Alam was scheduled to speak in a lead-up event to the Serendipity Arts Festival at British Council in New Delhi. The session, titled 'Political Dimensions of (Arts) Practices', had panelists unpack "positions around how to deploy a political statement through one's own creative practice".

Dissent isn't just distilled from an artist's tangible repertoire inspired from social and political upheavals. It can be gleaned from the simplest of actions, intentions and responses. As the audience waited on September 13 for the session to start in the afternoon, they were informed by the organisers that Alam will be joining via video call as his visa for entry into India was denied for reasons unknown. Through Skype, he discussed his works spanning 30 years through a PowerPoint presentation in the auditorium's screen—from framing jubilant scenes from Bangladesh in the 1990 when opposition groups managed to oust military dictator Hussain Muhammad Ershad to capturing the human tragedy of floods and cyclones that have repeatedly displaced millions in the country.

Alam spoke about his time in jail and how he productively utilised his time there by convincing the warden to allow the prisoners to paint. "The prisoners and I made 33 murals. There is a gallery in that jail now,” Alam said, decidedly in a mood that can best be described as bright and sunny while waiting at London’s Heathrow airport.

It wasn't just a one-way interaction, though. Curator of the festival, Rahaab Allana, sent across audience questions to Alam via WhatsApp after technical glitches on Skype could not accommodate a live Q&A session. Some members in audience whispered at the back, "Can we all send him questions on WhatsApp?", " Voice notes might be quicker". Had time permitted— the session had started late and there were other speakers awaiting their turn—Alam might just have fielded more questions on art and political activism.

If there are ways to circumvent visa denials with common-sense and quiet grace, this deft move by Alam can certainly be an inspiring example.