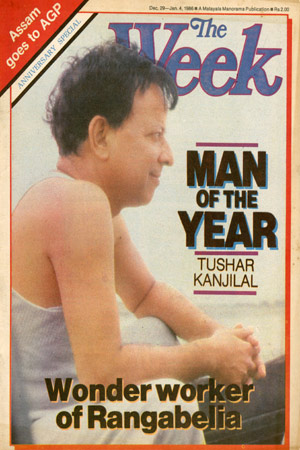

Eighteen years ago, Rangabelia island in the Sunderbans had a guest from Calcutta. The high school on the island was going to have a new headmaster. The children were excited, the misery-marooned elders were just curious; in their kind of life they had little time for teachers.

As the boat cut across the waters of the Vidya river, the 32-year-old headmaster looked at Rangabelia. The island had not changed much since his last visit 11 years ago. But he had changed. Tushar Kanjilal was no longer a fiery revolutionary and had severed all his connections with the Revolutionary Socialist Party, perceiving that "revolution would ever remain a dream".

Kanjilal settled down in the quiet village with his wife and children and went about teaching the village lads about the world outside, its people and its sciences, things which had no relevance to them. Some time later his wife Bina also obtained a teaching job in the school and Kanjilal, the one-time revolutionary, was losing himself in the passivity of existence in Rangabelia.

For eight years, Kanjilal lived the passive, eventless life, although aware of the poverty and deprivation of the people of the island, but not disturbed by the knowledge. Then one day in 1975 he encountered a situation that most teachers in India have faced. It was so ordinary but it shook the innards of Kanjilal.

Kanjilal recalls it vividly: "It was the fourth period when a boy stood up and prayed for half a day's leave. He was feeling dizzy: He had not eaten anything for two days." Kanjilal gave him leave but the boy's plea had broken the stillness of the former revolutionary's mind. He issued a notice and by evening he learned that 47 of the 300 children had come to school without food. "I convened a meeting of all teachers in my room and we decided that the situation should change." The 'revolution' of Rangabelia had begun.

Kanjilal set out on his new revolution in the most scientific manner, as all true revolutionaries do. The first task, he knew, was identification of the enemy—his enemy was poverty and deprivation.

First he sent his students on a door-to-door survey of three villages—Rangabelia, Jatirampur and Pakhirala—to find out the magnitude of the problem. The survey revealed that the land-holding pattern on the island, as it always is in a feudal structure, was pyramidical: a few people owned most land and most people owned little land. While there were only 15 families that held more than 10 acres of land each, the number of families that held less than one acre was 248. However, there were only 15 families with no land.

The survey also revealed that only 25 per cent of the villagers were physically fit to work and the total debt burden of the 671 families in the three villages was Rs 1,56,053 of which Rs 1,07,900 was owed by 163 families. And the rate of interest charged by the usurers, in most cases, was more than 100 per cent.

Three hundred families were found to be starving for an average of 37 days a year. About 150 families starved for 78 days in the same period. Those engaged in daily labour got work only for 63 days a year and the rate of earning was Rs 4 a day. Fifty-seven per cent of the villagers suffered from malnutrition, 61 per cent from intestinal disorders and there was only one doctor in an area of 20 square miles.

That was the condition of these villages, just 130km from the then prosperous Calcutta, 28 years after Independence, 20 years after the launching of block development projects and 11 years after the establishment of panchayat raj in West Bengal. What could an ordinary schoolmaster do where the resourceful machinery of the government had failed?

Kanjilal realised that his revolution lay not outside the existing socio-political system, but within it. As a political worker he had seen visionaries attempting at economic solutions outside the system and how they had failed. The system had the potential to project solutions, it only had to be identified and exploited. Moreover, any attempt outside the system, however viable it be, would collapse against the coercive power of the state machinery. Therefore, his modus operandi had to be complementary with the state rather than competitive.

At that time the state agricultural directorate was headed by A.K. Dutta, "who was known as a madcap among his colleagues for his zeal and passion for work," says Kanjilal. Dutta was convinced that any solution to the economic problem of the Sunderbans lay in the agriculture option.

Dutta realised that the Sunderbans, though surrounded by rivers, depended on the monsoon for its monocrop agriculture. The land and the water in the region were highly saline. Dutta wanted to introduce cultivation of groundnut and cotton as a second crop during the winter months to supplement the farmers' income. He despatched Sushil Chatterji, joint director of agriculture, to the Sunderbans, where he met Kanjilal. Perhaps it was that meeting that changed the destiny of Rangabelia.

But there remained yet another problem. The Indian farmer is not easily understood by the urban mind of the planner. Completely dependent on traditional wisdom, the Indian farmer is not the type to gamble with his far too limited resources. He would rather confront the known evil than the unknown one. But show him results and he would be convinced. Who would do that?

It was then that Kanjilal came across Kushdhwaj Dey, who agreed to experiment with the new crops on one-third of his 2.66 acres of land. However, irrigation was a problem since the porous ground soil in the Sunderbans would not hold water. Kanjilal advised Dey to dig a pond to store water. That worked, with the result that many more farmers came forward to follow Dey's example in the following season.

There was yet another typically Indian problem. Most of the tiny holdings of the farmers had been mortgaged to usurers and landlords. And the loans advanced to the small holders had no chance of being paid back before a couple of generations' bonded toil.

Perhaps this is the point at which most visionaries part ways with the system and confront it. However, such an approach, Kanjilal knew, would be foolhardy. There had to be a solution, again within the system.

Kanjilal had noticed that the moneylenders and landlords were not cultivating the solvent land during the rabi season because of poor irrigation and they lacked the enterprise to experiment. So, he began a mass contact programme, meeting landlords, moneylenders and the debtor farmers, both individually and collectively. He requested the landlords and moneylenders to allow the debtor farmers to cultivate their own land in winter when the creditors were not using it. That, he reasoned, would help the debtors to make money and repay the debts. Undoubtedly, that was a new venture in class cooperation, a micro-level experiment of what the Mahatma himself had meant by trusteeship economy.

Once land had been obtained, other problems arose. Most of the poor farmers had no agricultural implements, as they had not been cultivating their land for some time. Secondly, there was the danger of those farmers who had not earlier mortgaged their land now doing so to raise money for their new venture. And the kind of capital needed for such an experiment was by no means small.

At that time, state planning board members, Pannalal Dasgupta and Ajit Narayan Hose (the former was a terrorist-turned Gandhian freedom fighter), came to the Sunderbans to study the problems of the area. In the Sunderbans at that time, in 1976, agriculture was at its primitive stage; there was no electricity, industry or irrigation facilities despite an abundance of water in the rivers which swelled and ebbed with the Bay of Bengal. The problem of the two planners was to find a meeting point between the demands of human development and environmental conservation in the Sunderbans forests.

Kanjilal met the two planners and discussed his ideas of development with them. He was insistent that the self-reliance of the farmer also meant rescuing him from the clutches not only of the feudal traditions but also of the unreliable market economy. His first suggestion was an ingenious crop mixture. In the kharif season the farmer should produce paddy, the basic cereal which he and his family would need for a year, and the winter crop should be mustard and other oil-seeds, potato, onion, chillies, among others, which could be put on the market enabling the farmer to repay his loans.

The scheme, as envisaged by Kanjilal, appealed to Dasgupta who asked him to submit his plan to the state planning board. However, the government had no money. So, Dasgupta, who was running a voluntary organisation called Tagore Society for Rural Development in Birbhum district, lent Rs 5 lakh from that organisation. With that, Kanjilal and his islander-friends started the Tagore Society for Rural Development at Rangabelia in 1976. Later a West German organisation called Bread for the World lent Rs 20 lakh.

The society which started with 671 families in three villages now encompasses an incredible area of 28 villages and 8,243 families. It covers a land area of 14,407 acres and 51,504 persons. In the last kharif season 7,630 families involved in the project produced paddy worth Rs 1,96,92,000 in 13,128 acres which means an average earning of Rs 2,581 per family, a sum which most of the farmers could not have dreamed of earning a few years ago.

According to Kanjilal, who is affectionately called Master Masai, what has happened in Rangabelia is not a mere 'green' revolution. The revolution, or the change, has happened in the mind of the villager, his outlook towards life and his concept of family and society.

To Kanjilal, rural development did not mean an increase in agricultural production in isolation. When he talked to Dasgupta 10 years ago, he was thinking of an integrated rural development plan, in which education of the villager was also important to sustain the scheme for a long time to come. But he was sceptical of the education that he and his colleagues were doling out to their students, which held no relevance to the recipients. Therefore, he recommended non-formal education in the three R's, agricultural training, and training in rural trades, imparted by the few literate unemployed in the village and the craftsmen. To break the vicious link between the marginal farmer and the moneylender-landlord, he suggested a centralised mutual benefit organisation which would lend tilling machines, fertilisers, pesticides and seeds. The price or rent of these goods and services would be recovered only after harvest. To solve the irrigation problem, he suggested digging ponds in each holding to store rain water.

The basic unit of Indian village life is the family and not the individual. Therefore, the Master Masai's approach to rural development is family-oriented, and not individual-oriented, as most government schemes are. Each family has to prepare its own plan twice every year—one for the kharif season and one for the rabi season—which includes services to be taken from the welfare centre for cultivation, the family's probable expenditure for six months including clothes, medicine and household articles.

Each village is divided into eight to 10 paras, each para consisting of 10 to 12 families. The family plans are scrutinised at para meetings and sent to the village committee for endorsement. They are then sent to the governing board of the centre. The board has no authority to alter the plan on its own, but it can request the farmer to make alterations according to the resources available.

Life in Rangabelia today revolves around three centres—the agro-service centre, the Kendriya Mahila Samiti and the education centre. The agro-service centre coordinates the agricultural activities of 28 villages. It not only lends agricultural implements, and sells seeds and fertilisers, but also lends warehousing facilities to the farmers. Loans are recovered in kind, on the basis of the price prevailing at the time of granting the loan. The centre also gives employment to local youth in its poultry farms, dairy and piggery. Said Birendra Nath Mondal, a primary schoolteacher-cum-farmer: "Since the inception of the project, we have forgotten about the role of government agencies or even the panchayat. All our farming needs are met by the society."

Kanjilal realises the important role played by women in the society. The Mahila Samiti, started by his wife Bina, educates the women in various trades like weaving, tailoring, mat-making, poultry, fishery and vegetable gardening. In 1984, the total production of the samiti surpassed Rs 1.6 lakh. Trained girls can buy sewing machines and other implements from the society at subsidised rates. The vagaries of the market economy do not affect them because production is always dictated by the community's needs expressed in the family plans.

Apart from training the village girls in craft, the Mahila Samiti also educates them on the need of family planning. Today, the womenfolk of Rangabelia show an astounding knowledge about birth control measures. Perhaps the island geography might have helped Kanjilal in this matter. On an island, it is easier to show the people that the availability of land is limited. Said Surama Devi, an elderly village lady: "With no scope of expanding the land, how can we expand our families? One more mouth means an increase of at least Rs 50 in the monthly family expenditure. We are trying to minimise the expenditure so that we can invest more in our small holdings to increase our earnings." Yes, the women of Rangabelia have learned to talk the language of the planners, who they are.

Being a teacher, the Master Masai cannot think of development without providing education. There are today 240 non-formal education centres spread over the 28 villages, each with a supervisor-cum-teacher, and about 40 students. There are no fixed classrooms. Classes are held for two hours six days a week and class hours are determined according to the convenience of the students who are also engaged in productive activities like fish and poultry farming. Teachers move with blackboards, chalk, books and attendance registers. from place to place.

Today, Rangabelia in the Vidya river is an island of prosperity, inhabited by a forward-looking population. The success of he project has compelled the government to build brick roads on the mainland to reach Rangabelia. There is no shortage of money in the project. Impressed by the success of Rangabelia, the National Agricultural Development Bank and the People's Action for Development have requested Kanjilal to prepare plans for certain other villages in the area. In spite of his diabetic problems, he is still busy with plans to extend the project to 100 more villages in the next two years.

But isn't the Rangabelia model an attempt in closing the village economy from the mainstream of the nation's economic life, as a nationally renowned economist had $aid during the initial stages of the project? Master Masai does not think so. He agrees that his is a protective economy model, but such a model can be worked out in any Indian village. "I am sure that in asking my fellow-villagers to be self-reliant, to forsake dependence on the market economy and to grow all their necessities by themselves, I have not chosen the wrong path. In 1976 the per capita income of Rangabelia was Rs 502.08. Today, it is Rs 1,038.72." Moreover, Rangabelia today boasts of schools, roads, hospitals, sanitary latrines and piped drinking water, all built by villagers who had not even heard of many of these things a decade ago.

Perhaps as that economist had alleged, Rangabelia is a closed economy, built up on an island, cut off from the national economic life. But then it is not Rangabelia's fault, but the fault of the national economy and its planners. The Rangabelia model has been found working to the complete satisfaction of its members, and that definitely cannot be said of the national economic model. Moreover, Rangabelia is no challenge to the system, it is only a complementary improvement on the system, yet a revolution in its own way. In the Master Masai's way, in the Indian villager's way, in the way he understands, assimilates and reacts to change.