Chilean Poet, a delightful literary novel by Alejandro Zambra, brings out the prominent and unique place poetry occupies in Chilean society. One of the characters in the novel says, “Being a Chilean poet is like being a Peruvian chef or a Brazilian soccer player or a Venezuelan model. We’re two-time world champions of poetry, having won two world cups of Nobel Prizes by Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral.”

Pablo Neruda became a rockstar poet across Latin America. Known as the ‘people’s poet’, he recited poems to large audiences of workers and common people besides the literati. He was invited by president Salvador Allende to read his poems at the National Stadium to an audience of 70,000 people.

Neruda lived and travelled around the world during his diplomatic postings. Unlike many poets who end up in poverty, addiction, alcoholism, sickness and premature death, Neruda became a millionaire and lived a healthy life of luxury and fame. He was elected as a senator. His iconic houses with large personal art collections in Santiago, Valparaiso and Isla Negra have become centres of pilgrimage for poets and tourist attractions.

There is even a 'Coast of Poets' in the Valparaíso, named for the four world-renowned Chilean poets—Pablo Neruda, Vicente Huidobro, Nicanor Parra and Violeta Parra. Visiting Nicanor Parra’s house is like a rite of passage for Chilean poets. Parra, who lived for 103 years till 2018, is famous for the 'anti-poetry' movement, a literary expression that breaks with the traditional canons of poetic lyricism. One of his most recognised works is Poemas y Antipoemas (poems and anti-poems), considered as one of the most influential Spanish poetry collections of the twentieth century,

Chilean Poet is the story of Gonzalo, a poet, and his step-son, Vicente, an aspiring poet. Since the novel is about poets, the prose of the novel is itself poetic, obviously. The book is filled with the names and stories of the famous Chilean poets and the less-well-known besides imaginary ones. The author takes the readers to the cafes, bars, bookshops, plazas and streets frequented by Chilean poets.

Gonzalo is an avid reader of poems of Chileans and from the rest of the world. Although he manages to publish his first and only book of poems, he gives up poetry after realising that his mediocre work could not get wider recognition and appreciation. During his schooldays, he falls in love with Carla. But she loses interest in him after some time. He tries unsuccessfully to impress her with poems. She marries Leon, gets a son, Vicente, and later separates from the husband.

After a few years, Gonzalo reconnects with Carla and moves in with her. But when he gets a scholarship for higher studies in literature in New York, he moves on. When he comes back to become a professor in a Chilean university, he finds that his ex-stepson Vicente is also preparing to become a poet. The book ends with a long conversation between Gonzalo and Vicente on poetry and they read out their poems to each other.

Here is a playful poem by Vicente about the genders in Spanish words, which is difficult for English speakers to understand and master:

In my language the words for winter, summer and fall are all male

Only spring is a female season

The wind is a he

But the snow is a she

A fingernail (she) and nail clipper (he)

A bottle (she) and its opener (he)

Night and midnight, hers and hers

Day and midday, his and his

Vicente falls in love with Pru, a New Yorker, who comes to Chile on a journalistic assignment. He comes to her rescue when she is lost in a Santiago street with a hangover. They have a one night stand when Vicente tells her that he is planning to become a poet. He introduces her to Pato, his friend and a poet, who tells Pru that she should write about the poets of Chile. She attends a literary party in which she witnesses the poets exhibiting their eccentricities and bonding like a family. She interviews lot of poets including Niconar Parra. These interviews and encounters are used by the author to bring out the different dimensions and personal traits of poets with a sense of humour.

He notes, “Poets are more awkward and more genuine. They work with words, but they don’t even know how to talk. Take them away from poetry and they start stuttering. That’s why they write poems, because they don’t know how to talk.”

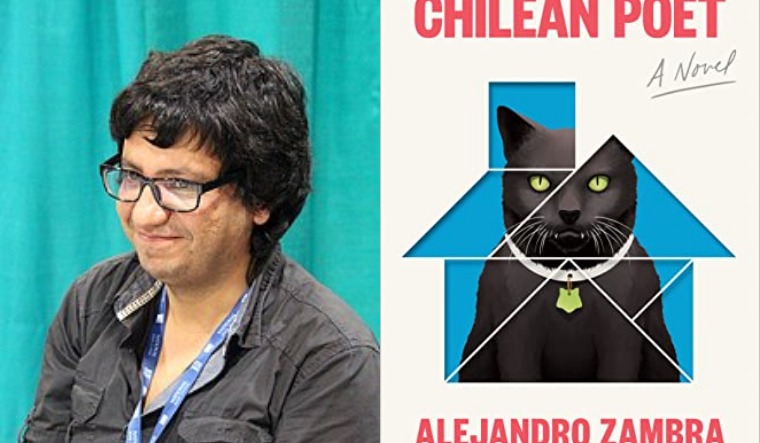

The author Alejandro Zambra is a poet himself and started his writing career with poetry first before becoming famous as a novelist.

In an interview, he says, “I am a poet by formation and most of what I have read in my life is Chilean poetry. My community was always poetry, and it still is—most of my friends today are poets who aren’t interested in writing novels. I think my move to prose had something to do with the defeat of poetry; not in the sense that I failed, but in the sense that I was unable to express the things that I wanted in poetry.” Like many other contemporary Chilean poets, he also tries to come out of the shadow of Neruda, saying,“A big part of Neruda’s work is to me utterly unreadable, but you have to understand me, I am Chilean.”

One of the reasons for Gonzalo to give up poetry is because he suspects his poems don’t really fulfil the requirements of truly new Chilean poetry, which has a duty to be political and must fight against the “capitalism, classism, centralism and sexism” of Chilean society. Though he subscribes to those struggles in principle, he is not sure that his poems express a social dimension in a clear enough way.

The author has brought in the ongoing socio-political issues of Chile, which has seen in the last decade student and public protests against inequality and marginalisation of masses. Vicente participates in the student protests demanding educational, political and social reforms. The following conversation between Vicente and his father Leon highlights the issue:

Leon says, “If you don’t get into a public university, I can pay for a private one. They’re almost all equally expensive in this damned country.”

Vicente replies, “There’s no point in you going into debt to pay for my college. I’ll go to college when it’s free.”

Leon: “You can’t be that naïve, Vicente. Do you really think education in Chile will ever be free?”

“That’s what they promised,” says Vicente with conviction.

Leon: “You believe politicians?”

Vicente: “No, but I believe in the people’s movement. And in the young representatives, the new ones.”

Vicente’s hope and optimism has the best chance of being fulfilled by the real-life recent political developments in Chile. Through protests in recent years, the people’s movement had forced the centre-right government of President Pinera to agree to change the constitution imposed by the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship. The new Constituent Assembly has gender parity, a first in world history. It has 78 men and 77 women. The first president of the assembly was a woman Elisa Loncon, member of the indigenous Mapuche community. She has now been succeeded by another woman Maria Elisa Quinteros. The assembly, which is currently debating and preparing a new constitution, is filled mostly with civil society activists who have beaten the traditional politicians and establishment parties of both the left and the right in the elections of May 2021.

In December 2021, the Chileans elected a young millennial leftist student activist, Gabriel Boric (age 35), who is taking over as the new president of the country on March 11. Boric’s cabinet has a majority of women, 14 out of the total 24. He has chosen a young, inclusive and progressive team. The average age of the cabinet is 49. Boric’s inclusive development agenda gives priority to social justice, empowerment of indigenous people and gender parity among other paradigm-shifting promises.

During the campaign he said, “If Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its grave.” Boric is an avid reader of poetry. According to a report, Boric has read the novel Chilean Poet and considers it one of his favourites. In an article in December 2021, Zambra wrote, “The generation of Gabriel Boric, that of our younger brothers, formed their own parties and refused to accept our traumas. They deserve our admiration, our affection and our gratitude.” Zambra called Boric also a ‘Chilean Poet’.

The author is an expert in Latin American affairs.