Under the provisions of TRIPS, countries are offered the escape route of compulsory licensing to enable production of essential drugs under patent, that may be scarce or expensive, setting aside patent rights on humanitarian grounds, to tide over a desperate situation of medical emergency.

While this may seem like the thing to do, a country must look hard to see that this provision, if invoked, can help alleviate matters and solve the current problem. If not, then, this 'Brahma Asthra' should be kept in abeyance for better use.

The main concern around compulsory licensing of international vaccines is that even if enforced, does India have the capacity to produce the vaccines, and if so, the timeline in which this can be done? Compulsory licences can only be invoked for limited periods of time. Would the pandemic wait for us or be over by the time we execute to a plan? Our problem is immediate as we are currently in the eye of a storm. Only real vaccines available today can help tide over the exigency. These can come from an immediate ramp up of in-country capability to the extent possible, supplemented by imports and donations from vaccine-producing companies such as Pfizer, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, Gennova, Sputnik, and others who agree to donate large number of doses to India for immediate use.

As a country that is now substantially entrenched in creating its own IP, our vision should be to rapidly scale this up and get fully compliant with what is considered global practice. Pharmaceuticals are only one piece of the puzzle, but there are other significant areas of IT, advanced research, design, and others where a large potential for IP creation exists. This goldmine needs to be explored fully and can be fired up so that innovation and discovery in the country can be spurred on. We would want to make sure that we don’t kill the goose that will lay the golden egg. Therefore, uphold patents.

Revisiting the arena of pharmaceuticals and vaccines, there are other halfway solutions to turn to such as voluntary licensing, a mechanism still overtly respectful of patents. Here, a company licenses its innovative products to others for free, a royalty or for distribution to restricted geographies. The recent licensing of the Russian Sputnik-V vaccine to six Indian companies is a case in point. Similarly, it may be easier to request our home-grown company Bharat Biotech to share its IP with others through similar licensing pacts; so capacity can be mobilised quickly and ramped up exponentially, where possible, in the shortest possible time.

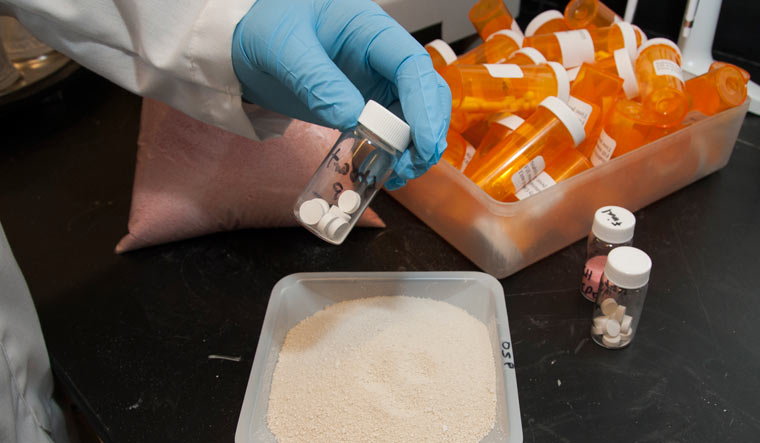

Another point of constriction could be the easy and abundant availability of raw materials that go towards vaccine production? These aspects as also the availability and quick deployment/redeployment of bio-reactors in the country may prove to be hurdles when it comes to execution. This aspect needs accelerated examination so real capacity can be switched on immediately and we are not left with a no-good mirage.

As background, patent protection gives market exclusivity to inventors. Such a monopolistic position usually translates into higher prices as compared to those that would prevail under competitive market settings. Consequently, the patented commodity becomes unaffordable to more consumers.

Moreover, when the product in question is essential to human health, such as medicines, the issue of patenting itself becomes contentious on humanitarian grounds.

It has been universally acknowledged that TRIPS conformity tends to hike up prices of patented medicines. There is no evidence, however, on its likely final impact on access. This is because TRIPS also includes multiple instruments to promote access, such as the issue of compulsory licenses, parallel imports, and incentivisation of technology transfer. Voluntary licensing is part of this larger set of available amelioratory measures.

also read

- Japanese Biopharmaceutical major Takeda sets up its first Global Innovation Capability Center in Asia in Bengaluru

- Here are the two medicines declared as ‘spurious drugs’ by Indian pharma watchdog CDSCO

- E-pharmacies to witness steady revenue growth

- Cipla calls Rs 53 lakh GST fine ‘arbitrary and unjustified’, plans to appeal

India issued its first compulsory license in February 2021, allowing Hyderabad-based Natco Pharma Ltd to make Bayer AG’s lung and kidney cancer drug Nexavar at one-tenth the price.

It was recently reported that the DIPP, which marshals policy decisions for intellectual property rights, is discussing a proposal to issue compulsory licences for three patented cancer drugs—dasatinib, ixabepilone, and trastuzumab.

Although innovators and patent holders abhor any such interventions that upset the rules of the market, they prefer to sign exclusive product licensing deals with local partners where possible to preempt sterner government compulsory licensing action, which discourages investments in long term exploratory scientific endeavour. Voluntary licensing under mutually agreed terms does help drug makers to expand their market and also avoid compulsory licensing, considered a death knell by innovators that leads to a drastic reduction in price. Voluntary licensing, on the other hand, still ensures the companies make a profit, albeit at a lower price and is a bit more palatable.

Given this scenario, and the paucity of readily available manufacturing capacity, compulsory licensing may not yield the results that the government is seeking. To overcome the pandemic, its first line of action should be sprucing up local manufacturing where easily and swiftly possible, seeking and deploying vaccines mobilised through aid and imports, perhaps also encourage voluntary licensing before stepping in to wield the threat of compulsory licensing that lowers India’s longer-term image and position of respecting intellectual property rights.

The author is President Council for Healthcare & Pharma.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of THE WEEK.