Researchers have built the first ever "living robot", or xenobot, by engineering frog embryos in the lab to behave like "living, programmable organisms," an advance that may lead to computer-designed life forms capable of delivering drugs in the human body.

The xenobots were millimetre-wide robots, designed by stitching together different cell types from a frog embryo in specific ways so that they could move towards a target on their own, and also based on how the cells interacted with each other, the study, published in the journal PNAS, noted.

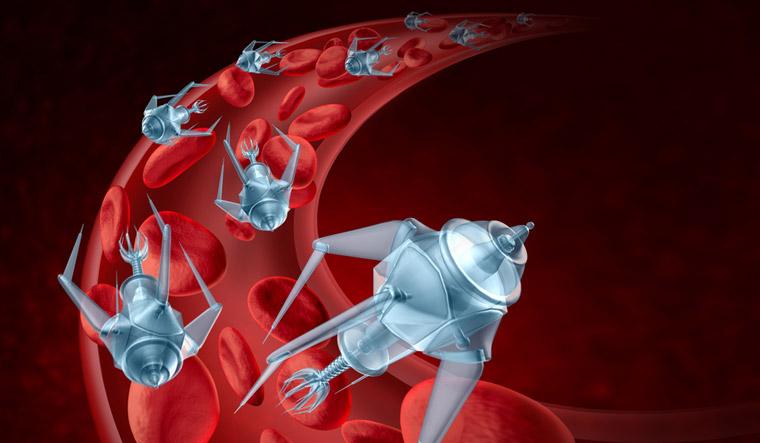

The bots were also engineered to pick up a payload—like a medicine that needs to be carried to a specific place inside a patient—and could heal themselves after being cut, according to the researchers.

"These are novel living machines. They're neither a traditional robot nor a known species of animal. It's a new class of artifact: a living, programmable organism," said study co-author Joshua Bongard, a computer scientist and robotics expert at the University of Vermont in the US.

According to the researchers, the xenobots may lead to novel machines in a wide range of fields like detecting toxic contamination in the environment, gathering microplastic in the oceans, and also scrapping out blocks in blood vessels.

The scientists developed a complex algorithm which could self-learn and evolve to create thousands of candidate designs for the new life-forms.

The algorithm reassembled a few hundred simulated cells into myriad forms and body shapes, over and over, in an attempt to achieve a task assigned by the scientists—like locomotion in one direction.

It ran on basic rules about the physics of what single frog skin, and cardiac cells can do.

The researchers said that the computer, after a hundred independent runs of the algorithm, selected the most promising designs for testing.

They then transferred the computer designs into life.

To achieve this, the research team first gathered stem cells—an unspecialised mass of cells with the potential to develop into any organ—from the embryos of African frogs, the species Xenopus laevis.

The scientists separated these into single cells and left them to incubate.

These cells were then individually cut using tiny forceps, and an even tinier electrode, and joined under a microscope into a close approximation of the designs specified by the computer, the researchers said.

The joined cells, came together into body forms never seen in nature, and began to work in unison, they added.

According to the scientists, the skin cells formed a more passive architecture, while the once-random contractions of heart muscle cells created an ordered forward movement which was guided by the computer's design, and by spontaneous self-organising patterns.

These responses of the different cells allowed the xenobots to move on their own, the study said.

According to the researchers, the bots were able move in a coherent fashion—and explore their watery environment for days or weeks.

They also found that groups of xenobots can move around in circles, pushing pellets into a central location—spontaneously and collectively.

Some of the bots were built with a hole through the centre to reduce air resistance, or drag.

The scientists could also create simulated versions in which this hole was repurposed as a pouch to successfully carry an object.

"It's a step toward using computer-designed organisms for intelligent drug delivery," Bongard said.

The xenobots also fall apart harmlessly, the University of Vermont scientist said.

"These xenobots are fully biodegradable. When they're done with their job after seven days, they're just dead skin cells," he said.

When the scientists sliced the xenobots in half, they stitched back together and kept going.

"And this is something you can't do with typical machines," Bongard added.