It was a Buddha Poornima without the smile. Rather, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, hardly 54 days into ruling third world's India with a rag-tag coalition, cocked a nuke at the superpowers with their mega-death bombs. Five earth-shaking tests in the sandy wastes of Rajasthan, and a sixth nuclear power has been born for the third millennium.

With a tremor that recorded around four on the Richter scale, the world has woken up to a sixth horseman, another claimant to the exclusive round table of nuclear white knights. Like the mythical Sir Galahad, the Indian knight has marched in to claim his seat with an empty scabbard. He would claim his thermonuclear sword when destiny decides.

Overnight, the world order, shaped in the post-Hiroshima 1950s and altered in the post-Cold War 1990s, has changed once again, causing confusion, chaos and panic across the irradiated planet. And cheers—some pronounced and some hidden behind routine condemnations.

As the US, stocking enough megatons to bomb out the earth, quoted from the scriptures of peace and disarmament and threatened trade sanctions as wages of nuclear sin, closer home, Pakistan threatened to test its own kilotons. But to a nation suddenly discovering its inherent strength, these were nothing more than fulminations of the insulted and the weak.

Unlike that first test, there is no apologetic suffix of 'peaceful' to the Buddha Purnima of May 11, 1998. There is a deliberate attempt to flaunt the yet-to-be-acquired weaponry. "These tests have established that India has a proven capability for a weaponised nuclear programme," the government declared in an official statement.

If the mantra of 1974 was 'peaceful', the unabashed hint in 1998 is 'weapon'. That is no boast, coming from a nation that has built some of the world's most accurate ballistic missiles. And now, the missiles are being promised of atomic crowns to take on not only Pakistan but also deter the Chinese dragon.

With all its intrinsic hawkishness, the BJP-led government has made it clear that India's strategic concerns are no longer confined to running a race with Pakistan. The Indian political and security establishment is suddenly thinking big and dreaming even bigger.

Incidentally, the new government is learnt to have already cleared the second-stage development of Agni as an intermediate-range ballistic missile. With a range of 1,500km to 2,500km, Agni can deliver a fission or thermonuclear warhead weighing up to one tonne.

The development of Agni, coupled with the recently proven thermonuclear capability, is bound to effect a major strategic shift, which Defence Minister George Fernandes has been talking about. For no Pakistani target is beyond a few hundred kilometres from Indian bases and Agni with its probable thermonuclear warhead will be useless against Pakistan. Agni naturally will be seen as a threat to China. The fact is that Agni, if launched from one of the forward bases, would have most of mainland China within its range.

Of course, no one believes that India can engage itself in an arms race with China, but the effort is most likely to be for building a minimum deterrence or the capability to inflict minimum unacceptable damage on China.

According to a study by Brig. Vijay Nair of the Forum for Strategic and Security Studies, a pro-nuclear think-tank, the desired weapon capability to achieve proportional deterrence against China would not be more than eight.

The desired capability, he says, would be "to pull out five to six major industrial centres plus two ports designed to service China's SSBN fleet. This makes a total of eight nuclear strikes." Of course, China would be able to inflict much heavier damage on India, but a minimal capability of eight strikes, he believes, would persuade China against military adventurism against India.

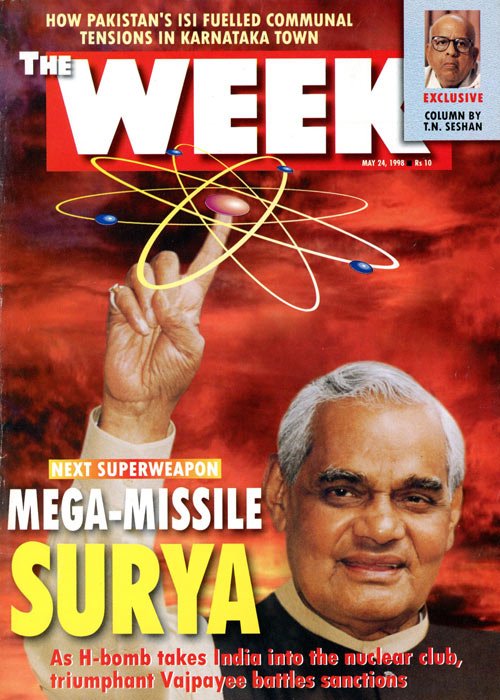

But what apparently is of further concern to the United States and the rest of the western world is India's hardly reported project to build an intercontinental ballistic missile. The project is learnt to have been christened Surya and the idea is to develop a missile, weighing 40,000 kilograms, which can deliver a megaton-yielding nuclear warhead across a range of 12,000km.

Very little is known about this project, except that as in the case of Agni, it would use both solid and liquid propulsion.

When shaped out of the blueprints where it is now sleeping, Surya, blazing with the fury comparable to the sun's heat, would be capable of hitting at any target on a good half of the earth. With Surya, India will no more be a regional nuclear power, but a global one because it can strike targets five times farther than Agni's range.

Scientific sources confirm that computer configuration is being done at a laboratory of the Integrated Guided Missile Programme of the Defence Research and Development Organisation. There is a heavy cloak of secrecy over the project, which is however disarmingly described as one of "the many dreams" of India.

Some years ago, even the thermonuclear bomb, the Agni missile and the Light Combat Aircraft were in the "dream" category before becoming realities. Among other current "dreams" of the DRDO is the MCA (Medium Combat Aircraft). Surya too can have a spectacular "rise" given the political will because the scientists, who have been buoyed by the continued run of successes in missile technology, are sure of getting Surya off the ground.

The immediate fallout of the nuclear test is a resurgence of nuclear weapon activity from across the western border. Pakistani leaders have already indicated that they can explode a device within three weeks, which might trigger a nuclear arms race in the subcontinent.

The problem facing both countries, particularly Pakistan, is in the availability of delivery systems. Theoretically, any of the conventional bombers can deliver a nuclear bomb. But in the event of known nuclear capabilities, the alerts would be higher and given the very high air defence capabilities available to both countries, bomb-carrying planes are unlikely to cross into each other's territory.

Naturally, both countries are preferring the missile route. If India has already developed, built and inducted the Prithvis with a range of 150 to 250km, Pakistan has recently tested Ghauri with three times the range. But India can develop its counter in the Agni, but like the Ghauri, it is yet to be developed as a full-fledged missile system.

The immediate attention thus has to fall on the Prithvis on the Indian side and the M-ll missiles on the other side. India is reported to have sufficient plutonium to build scores of bombs, but Pakistan's stockpile of weapons-grade uranium is believed to be enough for hardly 15 to 20 bombs.

In fact, India has certain inherent strengths drawn from the technologies it has preferred. India has chosen the plutonium route for the power reactor programme and that can now come in handy for making weapons. Far less plutonium is needed for making bombs than the amount of uranium needed. That makes plutonium better suited for making compact warheads. Once Pakistan starts operating its Khusab plant, it is expected to yield 10 to 14 kilograms of plutonium a year, which would be enough to make two to three bombs.

Pakistan's problem is that it is too heavily dependent on China. The Chinese have preferred the uranium route, which Pakistan can weaponise for its own use without even a test explosion. However, if Pakistan wants a warhead-based plutonium design, it has to conduct a test.

There are other inherent strategic advantages too for India. In the event of a conflict, Pakistan will be forced to disperse its M-11 missile arsenal to protect them from being destroyed by an Indian strike. In other words, the missile batteries will have to be moved rearward. This will reduce their ability to penetrate Indian airspace. On the other hand, India with its greater strategic depth can deploy its missiles deeper inside and still strike Pakistani targets.

Pakistan will overcome this problem as it develops its Ghauris and Ghaznvis, which can strike at targets deep inside India. India's answer would be Prithvi and Agni, but Vajpayee and his colleagues want to be ready for the threat from China and maybe other sources in the Asian region, for which they would need the deterrent of a nuclear-tipped Surya. But the immediate concern would be of acquiring air defence systems capable of detecting and destroying ballistic missiles. That is a tall order, given the fact that there is still no credible technology to counter ballistic missiles.

This article is part of a series from THE WEEK on the 20th anniversary of the Pokhran-2 nuclear tests undertaken by the government of Atal Behari Vajpayee. The Pokhran-2 tests—which saw India test 5 nuclear weapons at Pokhran, Rajasthan on May 11 and 13, 1988—led to India declaring itself as a nuclear weapons state. This series covers archival materials on how THE WEEK covered the Pokhran tests in 1998, the preparedness of India's military in a nuclear age and the threat of terrorists getting their hands on 'dirty bombs'.