It has been six decades since communities in the Malenadu region were uprooted in the name of progress and development. They are still fighting for basic amenities in the villages where they have been resettled.

Sharavathi river basin houses three major reservoirs apart from several small check dams and balancing weirs | via Commons

Sharavathi river basin houses three major reservoirs apart from several small check dams and balancing weirs | via Commons

It was in 1905 when renowned engineer Sir M. Vishveshwaraya saw the roaring torrents of Jog, the second highest plunge waterfalls in India, and exclaimed: “What a waste!” It was his visionary imagination which first seeded the idea of harnessing hydel power from River Sharavathi, considered a lifeline by many in the Malenadu region of Karnataka.

Today, the Sharavathi river basin houses three major reservoirs apart from several small check dams and balancing weirs. “From the earliest dated alteration of the Hirebhaskara (Madenur) Dam in 1932 to Linganmakki in 1964 and to the latest Sharavathi Tail Race Project in 2001, Sharavathi has been one of the most stressed and overused rivers in Karnataka,” says Na D’Souza, a Kannada novelist who has written extensively about the social regression that the displaced village communities had to face.

Owing to the series of dam obstructions, many agriculturally dependent communities of the Western Ghats were uprooted and evicted in the name of progress and development. Even after six decades, many of these displaced sufferers are fighting for basic amenities and appropriate land records in villages where they have resettled. I spoke to several farmers from Shetihalli and Purdaal, two rehabilitated villages that fall under the limits of the Shettihalli Wildlife Sanctuary, to understand their issues first-hand.

Displaced or banished? The case of Shettihalli

The kind of social regression (of the displaced communities) that Na D’Souza talks about in his fiction is not too hard to imagine if one is just travelling to the neglected hamlet of Shettihalli. The road to this settlement is a muddied track that cuts right through the lush greens of the sanctuary, tucked deep in the semi-evergreen forests. Among freely roaming herds of deer, one can also spot distant electric poles without connected cables.

Located 18 kilometres from Shivamogga, a district that gave Karnataka four chief ministers since independence, Shettihalli lacks elementary conveniences such as pucca roads, electrification, drinking water facilities, a government high school and a primary health centre (PHC). The village is home to over 80 families (almost all of them belonging to communities displaced due to the Linganmakki Dam) living in scattered houses located on plots growing paddy and areca nut palms.

Even as I sit down to talk to Manjappa Naik and his son Ganpathy in their damp house, the early monsoon rain pours outside without respite. Ninety-five-year-old Manjappa was forty when he was bundled out, among other bonded labourers from Salgalale village in Korur Hobli, into lorries and then dropped off at Shettihalli.

Constructed in 1964, the 1819 feet tall Linganmakki Reservoir is the main feeder for the Mahatma Gandhi Hydro Electric Power Unit. The dam submerged over 300 sqkm of land and displaced 22,698 families who were then rehabilitated on 13,067 acres of forest land. The backwaters of this ambitious hydel power plant have also submerged roads leading to several villages in the Sharavathi valley, cutting them off from the mainland.

“As the backwaters of the Linganmakki Dam started rising, the government showed us other fertile lands irrigated by the Bhadra (Lakavalli) Dam for resettlement. But we chose Shettihalli over them due to its proximity to the forests,” says Manjappa with a strange sense of guilt.

Ninety-five-year-old Manjappa was forty when he was bundled out, among other bonded labourers from Salgalale village in Korur Hobli, into lorries and then dropped off at Shettihalli.

Ninety-five-year-old Manjappa was forty when he was bundled out, among other bonded labourers from Salgalale village in Korur Hobli, into lorries and then dropped off at Shettihalli.

“These people never lived in Bayaluseeme (semi-arid lands), madam. They have always been heavily dependent on the forests for fodder, firewood and even medicines,” explains Ganapathy, justifying his father’s choice, which according to him, “made all the difference’’.

It was in 1974 that the government declared the forests surrounding Shettihalli as a wildlife sanctuary. Locals like Ganapathy say over 60 villages come within the limits of the sanctuary, 75 per cent of which are populated by resettled communities from the backwaters. “The table sketch for the sanctuary was prepared without considering the needs of the displaced who have cultivated revenue plots within the sanctuary for years,” shares an anguished Ganapathy. Guidelines under Forest Acts prohibit electrification and tarring of roads leading to Shettihalli.

“The city bus stand and the government hospital of Shivamogga also come under the limits of the wildlife sanctuary. But we have been the worst victims of such a short-sighted decision since the Sanctuary is named after our village,” he adds.

“We lost our lands, we lost everything”

Unlike zamindaars (odeyas), who were compensated with cultivable lands and cash as per the now-redundant Land Acquisition Act 1894, tenants like Manjappa who leased and tilled their ‘odeya’s land’, received nothing except paani (mutation extracts as proof of cultivating a portion of their land) on the basis of which they were allotted a few acres of bulldozed forest land in Shettihalli.

According to Ganapathy, most of the 25 early resettled families were just asked to cultivate the lands surrounding their dwelling place without receiving proper title deeds. “Hence, they failed to get Khata extracts (Form 8A) for the lands they cultivated. Since most of them were uneducated and vulnerable in their new settlement, they did not care to acquire proper land records. Till today, many farmers here do not have phodi patra (document of bifurcation of land with old and new survey number). Several plots are merged in a single survey number,” he adds.

Na D’Souza, who served for over thirty-four years in the accounts wing of the Public Works Department in Sagara, was witness to instances of corruption and harassment by public officials to clear out compensation cheques issued to displaced communities. “Many officers troubled those voiceless and helpless people and failed to show any empathy. The resettlement and rehabilitation procedure could have been done more fairly, had the government machinery worked well,” says the 82-year-old writer.

“In the initial days (late 1960s), we had to walk to Shivamogga for the weekly sante and buy groceries. On our way back, we were most scared of wild elephants,” recalls Manjappa, hitting his forehand with his palms.

“We lost everything,” groans Manjappa in a heavy voice. His eyes well up and his voice dips further as he repeats: “We lost our lands, we lost everything”. The meekly built old man recovers after a long deafening silence before offering to show me the way towards his relative, M.J. Rajappa’s house.

Living within a wildlife sanctuary

Manjappa leads me towards his relative, M.J. Rajappa's house.

Manjappa leads me towards his relative, M.J. Rajappa's house.

Unlike Manjappa’s gloomy house, Rajappa’s place is dimly lit with solar bulbs. In the backdrop, the rain lashes incessantly. I can sense how monsoons mark a particularly difficult period for the people of Shettihalli.

“Heavy rains and slush render the mud road inaccessible. The bus connectivity is only up till Purdaal which is over 10 kilometers away,” says Rajappa as he greets us. The villagers of Shettihalli have to depend on private vehicles like motorbikes to commute to Shivamogga in case of emergencies.

Over servings of by-two coffee, sixty-six-year-old Rajappa also recounts how mulugade (submersion by the backwaters) split up their joint family which tilled over 30 acres of land in their ancestral village of Hiremathur near Sagara.

Rajappa’s father and his younger brother were allotted 10 acres in Shettihalli while the other brothers of the same family were granted land elsewhere. Additionally, they received a compensation of Rs 750 for their house.

“When they first came here, the biggest liability of my father and uncle was to fend for their family and children. If anyone fell sick, the only option was to risk walking to Shivamogga by foot through the forest or die,” recollects Rajappa as he shares with us a painful memory.

“When the first trip of displacement lorries brought us here with all of our cattle and belongings, my mother forgot to carry sacks of salt. So, for almost a week, our cooked meals had no salt,” says Rajappa, who was just eleven when his family was displaced.

In a disheartened tone, Rajappa also shares with me how their repeated requests for facilities such as a PHC, high school and tar road have all fallen on deaf ears. “I have lost count of the number of governments that came and went by. Eminent ministers and politicians who visited Shettihalli have all made promises, but none of them came back to deliver any results”.

Manjappa who has been overhearing our conversation, naively adds: “The government has not really troubled us. It is always the Forest Department which does not provide permission for roads, electricity, etc...” Rajappa laughs and questions the 95-year-old if the Forest Department is a separate entity. Though Manjappa believes that it was their mistake to relocate here, one can’t help but wonder who is at fault when people have to live in darkness despite having sacrificed everything for the kind of development that never reached them.

Sixty-six-year-old Rajappa's large joint family was split up due to 'mulugade'.

Sixty-six-year-old Rajappa's large joint family was split up due to 'mulugade'.

Interestingly, Shivamogga is also the land of the Kagodu Chaluvali—an intense uprising against the zamindari system in the early 1960s. Manjappa’s face lights up when I ask about his participation in the infamous agitation. “We did go to Kagodu to participate in the movement, but the Indira Gandhi government called in the military to disperse the protesting tenants. So, we fled away giving some excuse,” he quips.

The protest which pressed for abolishing the tenancy system is believed to have benefited over six lakh landless labourers in the state with the passage of better land reforms that ruled ‘tiller is the owner’.

The issue of encroachment

Upon their arrival in the early 1960s, several large families of landless labourers, who had been compensated with little land, also pushed the boundaries of their allotted forest land and started cultivating crops like areca nut palm, paddy and ginger.

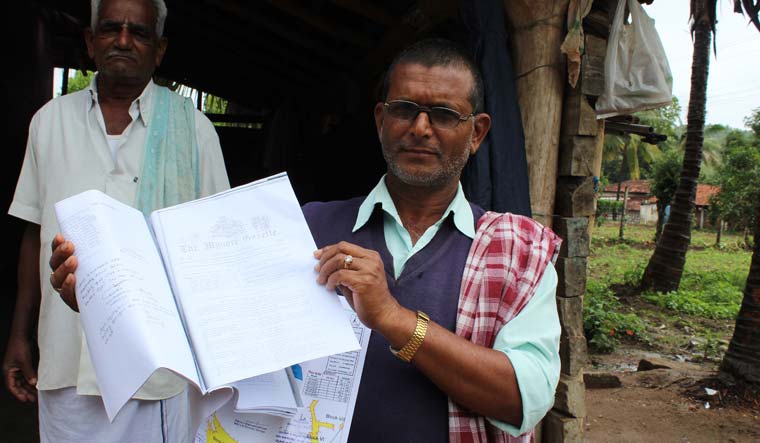

Sitting in his house that stands on a small patch of encroached land, otthuuvari jaaga as they call it, 53-year-old Hebbur Nagaraj in Purdaal village shows me a copy of the government notification dating back to 1963 that orders the “release and surrender of specific forest areas to the Revenue Department, for being given to the expropriated ryots for the purpose of rehabilitation”. However, many believe that this mutual transfer of appropriate forest land to the Revenue Department and vice versa was never done efficiently.

Six decades on, the forest and revenue departments are still engaged in a tussle that has severely affected the displaced communities in acquiring appropriate records for the land they have long cultivated. Nagaraj informs me that both the forest and revenue departments have recently conducted a joint survey to demarcate specific forest and revenue land in rehabilitated villages, which is likely to benefit them in acquiring complete land records.

A victim of double-displacement, Nagaraj’s family was displaced during the constructions of both Hirebhaskar and Linganmakki dams. “There was absolutely no compensation given to people affected by Hirebhaskar Dam. However, my family of 50 members was allotted almost 10 acres in Purdaal village for the 13 acres we lost in Sirigalale village during the construction of the Linganmakki Dam. Unlike in other power projects of Malenadu like Varahi, Chakra and Kaali, the Karnataka Power Corporation (KPC) also did not give any employment opportunities to people from the displaced families in the case of Linganmakki,” he says.

Nagaraj is angered every time the government categorises them as bagair hukum cultivators (farmers with no formal and documented ownership rights to the small plots of government land they occupy and continue to till). “Bagair hukum is when people encroach thick forest lands in plots other than their own and start cultivating. In the case of displaced communities, many farmers slightly pushed the boundaries of their rehabilitated land. This should be evaluated for humanitarian concerns before departments preach us law and mistake us for encroachers.”

A victim of double-displacement, Nagaraj’s family was displaced during the constructions of both Hirebhaskar and Linganmakki dams.

A victim of double-displacement, Nagaraj’s family was displaced during the constructions of both Hirebhaskar and Linganmakki dams.

A law graduate who educated himself in Shivamogga, Nagaraj also believes that mulugade was a boon to many landless labourers unlike his Zamindaar father. “Gradually, it freed them from bondage and they ended up owning land. Today, many children of those displaced tenants are holding high paying jobs in the corporate sector and defense,” he says.

They still wait for their chance

Apart from the lands originally allotted to their displaced ancestors, almost everyone in villages like Shettihalli and Purdal have applied for and acquired land rights for the extra lands they have cultivated. Some have even bought it from other rehabilitated families who wanted to sell it off.

Rajappa acquired documents (including title deeds, Records of Rights, Tenancy and Crops and Saaguvali Cheeti or cultivation records) for nine and half acres of darkhast land,” that he cultivated in the early 1990s. Ganapathy got cultivation records for his six and half acres in 1994.

In what was debated as an election gimmick in the run up to assembly elections earlier this year, the Siddaramaiah government in Karnataka also conferred land rights to the first 650 of the 22,698 families displaced by the Sharavati Hydel Power Project in 1963 under Bagair Hukum, Akrama Sakrama, and other Forest Rights Act schemes.

Ganapathy’s son received fresh title deeds for one-and-a-half acres of agricultural land last January under the same scheme. However, many other farmers are still waiting for their chance to benefit from this phase-wise exercise that gives preference to the Sharavathi-displaced communities to claim rights over the lands they have tilled.

Shashi Sampalli is a Shivamogga-based journalist with ancestral roots in the villages submerged in the Linganmakki backwaters. When questioned about the sense of confusion clouding the land rights of these displaced communities, he lists the reasons that caused the logistical delay.

“Within just a 100-km radius around Shivamogga district, there are over five major dams; this has eventually led to the displaced communities tampering with forest land. Since Linganmakki was one of the earliest hydel power projects in Karnataka involving acquisition of land, the resettlement and rehabilitation of displaced farmers were done hastily, especially in the case of landless labourers. Moreover, the declaration of rehabilitated forest land as Shettihalli Wildlife Sanctuary without due consideration of the revenue lands and human settlements present there further complicated things,” explains the 42-year-old.

The dream of a better life

Shashi has also written extensively about the issues of displaced communities in Malenadu. He believes only a one-time settlement that duly considers the problems and challenges of rehabilitated people can be the solution. “Till today, several politicians have not solved the problems of bagair hukum cultivators because it serves as a vote bank issue during elections. In such a context, it is important for both elected representatives and various government departments to work together to confer appropriate land rights to the displaced communities by making some exemptions in law,” he suggests.

Multiple dam constructions and serial displacement have stressed the forest cover in Shivamogga (over 4,100 sqkm) district immensely. “If not for the wildlife sanctuaries, the forest cover would have reduced further from the present 20-21 per cent,” shares a senior forest official from the Shivamogga wildlife division.

“We do not view resettled farmers as thieves. We are just following our duties under the tenets of law; the hatred towards us is unjustified. Empathy cannot work when you are dealing with a complex social evil like encroachment,” he says, reiterating the kind of difficulty his colleagues in the forest department face when they have to differentiate between displaced communities and encroachers.

“It has been fifty-six years since we were resettled in Shettihalli. However, we are all still dreaming of a better life” shares a dejected Rajappa. With a power generation capacity of 55 MW, Linganmakki today provides electricity to big cities and towns. However, many like Rajappa who sacrificed their homes and lands for the same continue to live in darkness.

Shettihalli has now received sanction for power through underground cables running beneath the sanctuary. However, will people like Manjappa Naik live to witness the day when electricity reaches their homes? Only time can tell.

Amoolya Rajappa is a Bengaluru-based journalist