With the scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status on August 5, 2019 came unprecedented security measures and limits on communication that continue to this day. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and measures taken to contain it have led to the people of J&K being placed under a double lockdown.

As India and Pakistan continue their proxy war, the people of J&K yearn for peace and the restoration of democratic rights enjoyed across the rest of the country. At the same time, their sense of alienation grows.

Today, Kashmiris are treated with suspicion, penalised under draconian laws like the Public Safety Act (PSA), Armed Forces Special Power Act (AFSPA) and Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA)—the likes of which do not exist in major democracies. Journalists who report on inhuman conditions seen during lockdown are put behind bars without justifiable reasons.

The degree of human suffering has increased so much that a significant proportion of Kashmir’s people suffer from various mental illnesses including depression, constraining their ability to take sound decisions on matters both personal and electoral. The lack of gainful employment and business opportunities throughout the year only adds to their frustration.

The Supreme Court, too, has not acted fast enough to provide legal relief to the petitioners from Kashmir, as the Centre has pleaded that J&K be treated like a war zone.

Had there been an acceptable policy to treat all citizens equally in all matters—including access to digital platforms—as the Constitution of India mandates, the sense of alienation among the youth and the general feeling of victimhood could have been contained.

An assessment of political developments in J&K since independence indicates that there has not been a consistent and well-thought-out Kashmir policy to ensure sustainable peace and development and to promote the democratic participation of people in the decision-making process.

For instance, unlike any other federal state under the Indian Union, J&K has been under the direct control of the Centre. The three-tiered Panchayati Raj system, which guarantees good governance at the grass roots levels, has never been operationalised.

Likewise, even though several political leaders were placed under house arrest without assigning any reason for their confinement, the Supreme Court has yet to assign sufficient priority to the matter; a constitutional one that adversely affects the democratic rights of people.

The Central government has not pursued the policy pronouncements it makes made from time to time with any consistency. While the support of the people of Kashmir has been elicited for maintaining law and order, they have never been democratically engaged to resolve contentious issues such as, for example, the extent of political autonomy for the governance of J&K.

In a broadcast to the nation on November 3, 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru promised that the fate of Kashmir would be decided by the people. “That pledge we have given not only to the people of Kashmir and to the world. We will not and cannot back out of it,” he said.

What his successors subsequently said and did, however, is discussed below.

“Na Goli Se, Na Gali Se, Kashmir ki Samasya Suljhayge, Gale Lagane Se”

File photo of Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressing the nation from Lal Qila

File photo of Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressing the nation from Lal Qila

In Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Independence Day speech delivered at the ramparts of Lal Qila on August 15, 2015, he said that “Kashmir’s problems can be solved only by embracing the people of Kashmir, not with bullets or abuses.”

The government subsequently, after August 5, 2019, enacted unprecedented security measures in Jammu and Kashmir after its decision to abrogate Article 370 and reorganise the state of J&K into two Union Territories. Article 370 guaranteed nominal autonomy to J&K, which was rescinded to suppress and contain militancy through the Centre’s direct control of the region.

PM Modi said that to strip the special status of the state, these steps were taken in a “completely democratic, open, transparent and constitutional manner”. Regarding its constitutionality, however, the government’s decision was challenged in the Supreme Court of India—which is yet to deliver its judgement.

Contrary to what PM Modi said on Independence Day in 2015, his government’s action on August 5, 2019 was unexpected and unbelievable. All this does not constitute an acceptable policy on Kashmir.

Insaniyat, Jamhuriat and Kashmiriyat

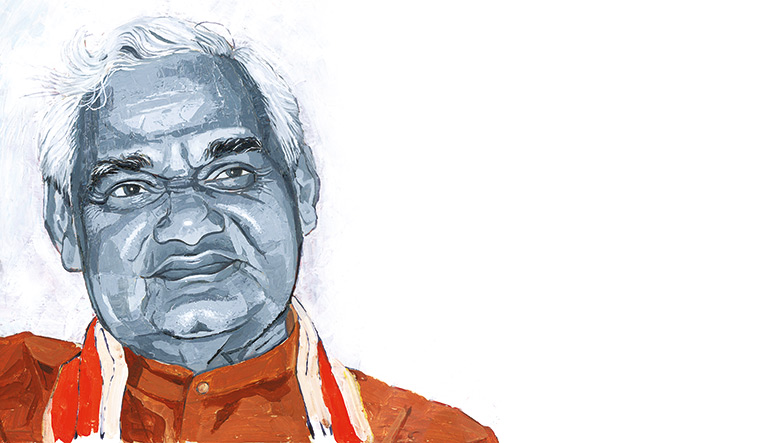

During his Prime Ministership, Atal Bihari Vajpayee made sincere and concerted efforts to reach out to all the stakeholders in J&K as well as in Pakistan. Eventually, India and Pakistan came closer towards signing a peace accord at Agra. They did this by accommodating the wishes and aspirations of people through a doctrine outlined by Vajpayee: Insaniyat, Jamhuriat and Kashmiriyat (Humanity, Democracy and Secularism).

The President of Pakistan, Pervez Musharraf was on board, but the proposed accord could not be signed for reasons known to both the parties.

Dr Manmohan Singh not only tried to pick up the thread that the Vajpayee government had left but also took additional steps to address the problems faced by the people of J&K. For instance, Dr Singh constituted various Experts Groups to perform objective studies of issues facing the state. These groups looked at improving centre-state relations to ensure maximum functional autonomy, facilitating trade across the Line of Control (LoC) to promote business and employment across the region, improving the quality of governance over J&K as well as its economic development and building a grievance redressal mechanism to deal with human rights violations including resettling the displaced Kashmiri Pandits.

But, the confidence building measures (CBMs) that were then recommended could not be satisfactorily implemented.

Further, on the recommendation of an ‘all-party delegation’ that had visited J&K to find out the causes of turmoil in 2010, the Centre appointed a three-member Group of Interlocutors to suggest ways and measures to promote peace and development in J&K. The Interlocutors’ report, submitted in 2011, was titled ‘A New Compact with the People of J&K’, and was based on consultations with a massive representation of stakeholders from across 22 districts.

Sadly, the Central government kept the report under the carpet and chose not to proceed with the interlocutors’ recommendations. This shows the lackadaisical attitude of the Central government towards the problems and issues faced by the people of J&K.

The manner in which the Centre has dealt with J&K—including the lack of an effective democratic process to form governments at different levels and the use of brutal force to suppress the voices of youth—has widened the sense of alienation and disillusionment among the people of J&K as well as among the Kashmiri Pandits.

Successive governments have promised resettlement of the Pandits but it has remained a hollow promise. They must also be taken on board for resolution of all the contentious issues, especially their rights to live with dignity in their home state.

The Shimla Agreement

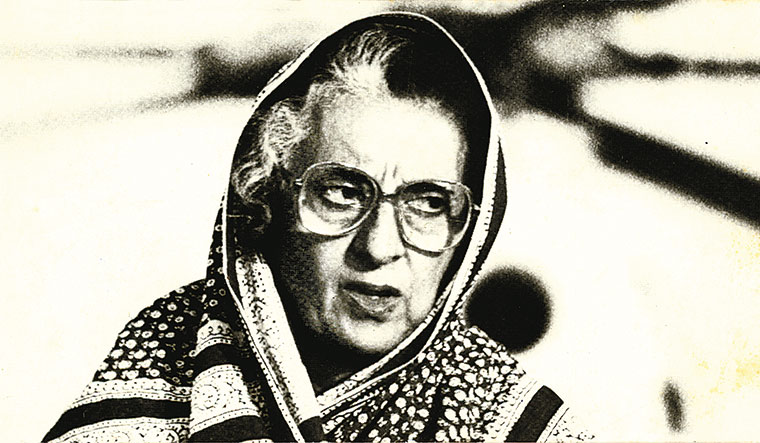

Under the Indira Gandhi government, India and Pakistan agreed to the following points under the Shimla Agreement 1972:

1. That the principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations shall govern the relations between the two countries.

2. That the two countries are resolved to settle their differences by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations or by any other peaceful means mutually agreed upon between them.

Further, under the Shimla Agreement, the two countries agreed, inter alia, that “Pending the final settlement of any of the problems between the two countries, neither side shall unilaterally alter the situation and both shall prevent the organisations, assistance or encroachment of any acts detrimental to the maintenance of peaceful and harmonious relations.”

Yet, ignoring all these commitments, the decision to abrogate Article 370 and reorganise the state was unilaterally taken by the Centre. Without assigning a clear reason, political leaders of all hues were put under house arrest.

Inconsistent policy

An Indian security force personnel keeps guard alongside a road during restrictions after the government scrapped the special constitutional status for Kashmir, in Srinagar | Reuters

An Indian security force personnel keeps guard alongside a road during restrictions after the government scrapped the special constitutional status for Kashmir, in Srinagar | Reuters

It emerges from the foregoing that India has neither evolved a consistent Kashmir policy nor has it followed what was promised and agreed with the stakeholders, mainly Kashmiris. This also indicates that we do not have a well-thought-out strategic and diplomatic approach to deal with Pakistan’s sponsoring of cross-border terror activities, nor a plan to promote economic trade and people-to-people contacts.

India cannot solve the Kashmir problem without a sound Pakistan policy.

Given the emotional attachment between the familes divided by the border and the cultural affinity among people of both sides, there is a need to improve people-to-people contacts. Countries that support cultural exchange programs across their regions and that promote economic and business trade, do not engage themselves in war-like activities or maintain adversarial relations.

The lack of cordial relations with Pakistan—often seen in the war of words between leaders of both countries—is perpetuating the security-related crisis and adding to the problems of insurgency and militancy in the J&K state. Scarce resources are drained that could otherwise be utilised for the welfare of the people.

India-Pakistan tensions not only affect the prospect of peace, they also also harm the economic atmosphere required to make India an attractive destination for domestic as well as foreign investors.

When India has managed to finalise border issues with Bangladesh by exchanging enclaves as per the people’s wishes, the Kashmir imbroglio that haunts Indo-Pak relations must also be settled.

But, instead of diplomatic efforts, India is engaged in a prolonged proxy war with Pakistan and this fight is without the help and support of the people of Kashmir. A strong committment to continuing dialogue between the two sides is necessary.

It does not help that Islamophobic comments and tweets by some members of the ruling party, made often for electoral gains, spoil the chances of winning the hearts of minorities—who constitute a majority in J&K. For a few among the youth, angered by maltreatment mainly from officials and security forces, they move closer to the separatists ideology. The use of brutal force only alienates them further.

Therefore, without evolving an acceptable Kashmir policy in consultation with all the stakeholders, particularly the youth who dream of a shining India, the restoration of sustainable peace would be an elusive goal. The fallout of COVID-19 requires a renewed approach to promoting economic trade and business in the region.

M.M. Ansari is a former member of the UGC, CIC and interlocutor on Jammu and Kashmir

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of THE WEEK