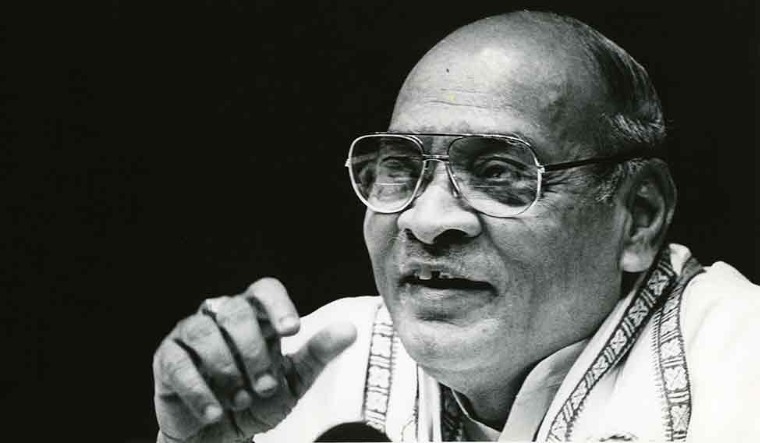

Humiliation and honour alike dogged one of the most successful political leaders of this country, the late P.V. Narasimha Rao. In the run-up to the 100th birth anniversary of the former prime minister, which falls next year, it is time for the latter.

The ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) party in Telangana has declared that it will observe a year-long centenary celebration starting June 28 and has sanctioned Rs 10 crore for this purpose. The party also wants Bharat Ratna conferred on the former PM. Narasimha Rao was not remotely connected to the TRS party. A staunch Congressman, it is safe to say he was an integrationist and never openly voiced his support for a separate state of Telangana. He was not known to be close to Telangana Chief Minister K. Chandrashekar Rao at any point of time. So, why is the TRS party going all out to own this “Telangana Bidda” (son of the soil)?

Narasimha Rao held several key political posts throughout his life; chief minister, Union home minister, external affairs minister, human resource minister and prime minister were some of them. His governance was lauded for introducing revolutionary land reforms in Andhra Pradesh and economic reforms at the Centre. Though his intellectual prowess and visionary ideas were appreciated, the man himself is often perceived to have been ill-treated and left in the lurch.

There is always a lingering feeling of sympathy among Telugu-speakers for Narasimha Rao.

Hailing from the Karimnagar district in north Telangana, a hotbed of revolutionary left activism and the land of heightened Telangana sentiment, Narasimha Rao was well-known as a freedom fighter, a lawyer and, later, as a political leader. After serving consecutive terms as a legislator from Manthani in Karimnagar district, where the Brahmin community (of which he was a part) holds sway, Narasimha Rao became chief minister of Andhra Pradesh in 1971.

During this term, he released the excessive land holdings of individuals and paved the way for the redistribution of smaller lands among the marginalised communities. This is probably one of his bravest decisions as it rubbed the rich and influential sections on the wrong side.

There are different explanations of why Narasimha Rao took this decision. Some say he genuinely wanted to help the poor, others say he was committed to his reforms. There is also the view that he sought to politically weaken feudal groups within the party. According to political analysts, his turbulent phase began almost immediately.

It is believed that both the capitalist peasants of coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema and the feudal lords of Telangana, mostly from the upper castes and within the party, conspired to pull him down. After stepping down as the CM, Narasimha Rao was relegated to being a low-key leader in the state as he did not have a powerful lobby or an influential community backing him.

As a senior Congress leader recollected of this phase, “The Congress high command also could not step in and back him and Congress once again went into the hands of the powerful leaders from [a] feudal background,” he said.

He felt the impact of this for two decades. Narasimha Rao shifted base to Delhi as he discharged his duties as the general secretary of the AICC. The gap widened between him and the region where he was born, which he had led and that he had reformed. Though he won twice from a parliament seat in Andhra Pradesh, he lost the next time due to internal politics and other reasons and then shifted his constituency to Ramtek in Maharashtra. People close to him remember this time as a demoralising one for Narasimha Rao as it felt like the region as well as the state chapter of the party had disowned him. While the legacy of most chief ministers of united Andhra Pradesh is structured to live on in some form, Narasimha Rao as a CM seemed doomed to be forgotten.

Delhi, however, favoured him, for he was known to be proficient in 14 languages. He was widely acknowledged as a draftsman for former PM Indira Gandhi for her speeches, policies and resolutions. He also enjoyed good relations with former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and after his assassination, went on to become the PM in a minority government. Here, Narasimha Rao successfully completed the five-year term that he could not as a CM.

“In 1990, he went to the US for a bypass surgery as his daughter used to live there. I was a student pursuing my higher studies in the US that time,” recalled his grandson, N.V. Subhash, who is now a BJP spokesperson in Telangana.

“He was surrounded by some of his family members before the surgery. One of us asked him what he would do if he ever became the prime minister. It was a very casual question. He said he will change the country so much that there will be more investments and industries. We all laughed innocently not knowing what he meant. But, we now know.”

Subhash recalls that his grandfather was never after money and even the cost of bypass was borne by family members and his admirers.

His life was not without blemishes. The first time he faced serious criticism was as home minister when Indira Gandhi was assassinated. He was accused of failing to control the anti-Sikh riots in the aftermath. In the same year, 1984, he was once again questioned over his role in flying out Union Carbide CEO Warren Anderson after the Bhopal gas tragedy. However, the biggest dent to his image came in 1992, when under his tenure as prime minister, the Babri Masjid was demolished and deadly communal riots raged across the country.

As prime minister, Narasimha Rao was known to be instrumental in the liberalisation of the economy, encouraging privatisation and also keeping the Nehru-Gandhi family at bay. In addition, he accelerated India’s nuclear weapons programme.

After he stepped down as PM and Sonia Gandhi was brought back as AICC president, Narasimha Rao ceased to be significant. He was mired in corruption cases, left to fend for himself as the party refused to support him morally, according to those close to him. What was more heartbreaking for him was that his own party men would avoid him, let alone consult him on important issues.

“In the early 2000s, before he died, he was a regular to Hyderabad. Only a couple of party-men used to tiptoe their way in to meet him in secrecy. Most did not want to be in the bad books of the high command, and hence, did not make any efforts to be in touch with him. He almost became a stranger in his own party and land,” said a senior Congress leader.

His death was anything but honourable. His body was not allowed inside the AICC headquarters in Delhi and was flown to Hyderabad when Congress was in power at the state and centre. The place allocated for his funeral and memorial was in a small piece of land in the recreational zone on the banks of Hussain Sagar. What was unforgettable was also the improper arrangements for his funeral, not befitting a former prime minister.

Sixteen years later, the glory of the only prime minister of India from Telangana and the first one from south India is expected to be richly remembered. In P.V. Narasimha Rao, the TRS party sees a self-made man, a Telanganite who never got his due and most importantly, a tall figure who was humiliated by their political rivals, Congress. A year-long celebration also means a year-long period of discomfort for the Congress, who can neither openly own Narasimha Rao nor disown him. A year-long period of refreshing the memory of how Congress treated Rao, giving scope for more discussion on his life.

With a grandson in tow, the BJP is more than happy to be on the same page with TRS on this issue—possibly because on many occasions, Narasimha Rao was accused of being sympathetic towards soft Hindutva and was also known to be on friendly terms with RSS leaders.

For the BJP, Narasimha Rao, as an alleged target of the Nehru-Gandhi family, was also a victim. Politically and morally, the TRS stand to gain from the centenary initiative, even as they put the grand old party in a tight spot in the state.