Historian V.N. Datta had been bed ridden for years, but that didn’t seem to dampen his spirit. Datta sahib—to the larger academic world—still spent his time reading history, writing history, discussing history. He was 94.

Datta belonged to the first generation of historians in Independent India who chose to delve deep into India’s history to craft the story of their country. His book Jallianwallah Bagh changed the narrative of General Dyer’s massacre adding conspiracy to the mix. Datta grew up ten minutes from Jallianwallah Bagh—his elder sister had heard the bullets and he walked past the bullet ridden walls for years.

“I feel that the massacre was the result of a well-planned conspiracy aimed at bringing together a crowd which could be killed by Dyer,’’ he said in an interview to his daughter Nonica Datta, also a historian at the Jawaharlal Nehru University. It was the first book on the massacre.

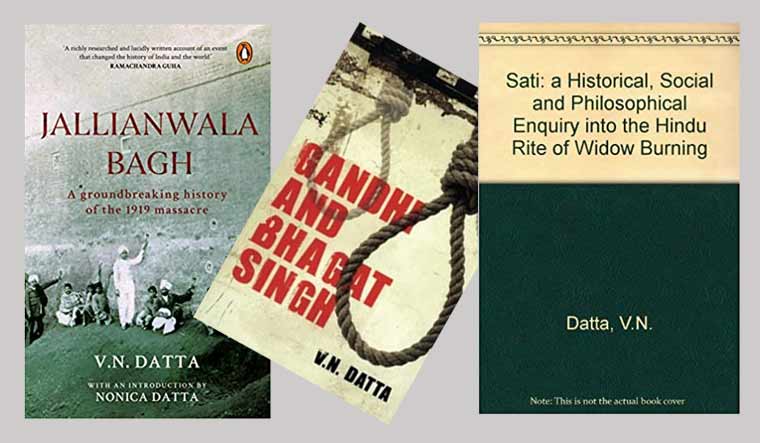

Datta was prolific as well as diverse. He has written extensively on varied topics from sati to Madan Lal Dhingra. His books include Amritsar: Past and Present; Sati: A Historical, Social, and Philosophical Enquiry Into the Hindu Rite of Widow-Burning; Maulana Azad, Gandhi and Bhagat Singh; New Light on Punjab Disturbances (2 volumes), and a biography of the revolutionary, Madan Lal Dhingra and the Revolutionary Movement. He also wrote a book on the history of Kurukshetra.

The Partition generation like many others refused to let the bloodshed colour his outlook. “He was a secular,’’ says Professor K.C. Yadav who has known Datta from the 60s when he joined the University. “There was no Hindu or Muslim for him.’’

He studied in Government College Lahore, went to Cambridge and taught at Kurukshetra University. He was known for his candour. At an event at Kurukshetra University to mark its golden jubilee in 2007, Datta, who was Professor Emeritus of the University, delivered a speech in which he said out of the 31 VCs the University had in 50 years only six persons were really qualified to be the Vice-Chancellor of a university.

While he was known for speaking his mind, Datta was also known for his generosity and encouragement. He has been a guide for a whole generation of young historians. “His memory was incredible,’’ remembers Yadav. This association continued even after Datta retired and Yadav would visit him at home to sip tea and discuss their favourite topic in common history. "He was a friend, philosopher and colleague."

Datta devoted his day to the past for years. “In the morning after breakfast he would start reading history, writing history, discussing history, all the while he would be in the realm of history. After retirement he would punctually go to India International Centre where he would sit on his seat in the morning and retire in the evening.” His memory was legendary. "You could call him up and ask about a certain period in Punjab and he would remember the details, who was who and what the issues were. His facts were always on his fingertips."

It was an accident and a broken hip bone that forced him to be immobile. “It was a long time.” Asked whether he was ever dispirited, Yadav says: “It is not an easy job. Even super humans get fed up with that kind of life. He was always active.”

He was General President of the Indian History Congress, Resident Fellow of Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, and a visiting professor to a number of universities including Moscow, Leningrad, Berlin. He also has a new book coming out on Sarla Devi Chattopadhyay. “He was a bold man who fought death boldly,’’ says Yadav.