What surrounds us shapes our reality and we shape our surroundings. This circular relationship is deeply fascinating and incredibly complex. What goes behind the processes is truly intriguing and the subject matter of a number of studies as well as a burning topic of research. I approach the relationship from a perspective of a lawyer, not only because I am one, but also because law and its systems, processes and indeed buildings are all about society and about proscribing, preventing and also facilitating and moulding. It affects all our lives from birth to death, beginning with a birth certificate that gives one legal rights all the way to the death certificate, with a number of scenic disputes and events in between. Admittedly though, of course that is just a perspective and there are infinite possibilities to look at this relationship.

Buildings and architecture are one of the most obvious and stark places to search for the meaning and messages in our surroundings. Look at Chandigarh, one of the youngest cities, planned and executed in a newly independent India by a French architect. The utopic city was created with brutalist and solid buildings where none of the flair and the circular structures were replicated. A far cry from the arches and avenues of cities like Jaipur and Luteyns Delhi. The symbolic structure of the La Main Ouverte or the Open Hand monument stands for the ‘hand to give and the hand to take’ displaying openness and promise of collaborating. In many ways the city lived up to the promise. BBC in fact declared it to be the ‘best city in the world’. Nonetheless, it is a far cry from the states that it is meant to be a capital to. The open areas of sitting as well as street food do not lend themselves easily to sectors and markets. The High Court, again designed with French sensibilities, comes from a civil law tradition where the judge is afforded a much greater role. The canteen is comparatively small as litigants being accompanied by friends and family is not a common concept in France but in Punjab and Haryana on the other hand it is.

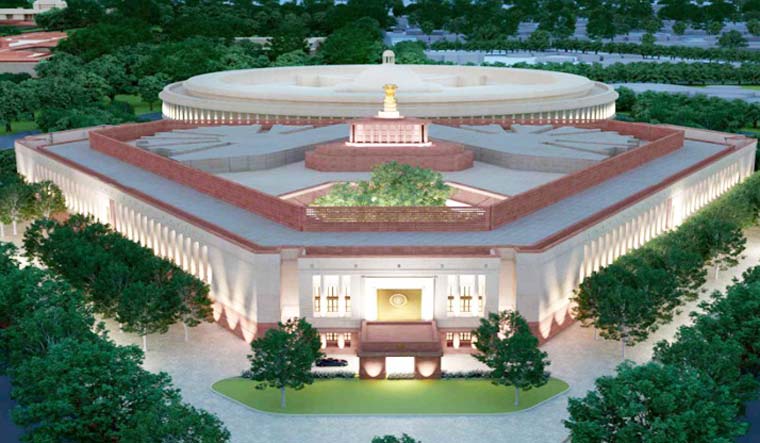

Rather fascinating, however, is how buildings ‘display’ power. In striking resemblance, the domes of Parliaments around the world have a striking similarity. The iconography and display of power is deeply fascinating. The Capitol in Washington has striking elements of the Capitol in Rome. City squares around the world are similarly nestled as public places. Such is the allure of power-displayed buildings that the United Kingdom Supreme Court was moved out of the House of Lords in the last decade, in a move to demarcate the separation of functions between the judiciary and the legislative.

India certainly has a similarly impressive architectural heritage. The Rashtrapati Bhavan for instance is flanked by the two arms of the government. Various temples, mosques, churches, gurudwaras, forts, palaces and tombs across the country stand testimony to the architectural genius of the country. Fatehpur Sikri, for instance, has elements of mixed religious symbols which truly amalgamate the essence of a secular India. Many ancient temples have entire stories etched on their walls giving an incredible insight into the India that was.

Universities, as places of learning, similarly have secret quirks in their architecture. It is rumoured that most classic buildings in the universities only display a facade to the outside world. The periphery walls, for instance, in Cambridge are impressive but the true awe only comes in once you are ‘in’. Whilst the outside world sees the ivy covered walls, those on the inside, the scholars, see the true nuanced architecture. In fact, the Sidgwick site in Cambridge houses a number of buildings including the famous Seeley Library. To the bystander the visuals are clear with the library that looks like an open book having a ‘conversation’ with the buildings housing divinity and other schools. The modern law school is mostly glass and metal symbolising an effortless flow of disciplines and an open-ness marked by transparency.

Cities, buildings, spaces reflect as well as mould the society and in ways that are subtle yet marked. The national capital is undergoing transformation with the Central Vista and what it displays about us is yet to be seen. It is, however, imperative that we pause and see what conversation the environment has with us. It is, after all, our space, our reality.

Vishavjeet Chaudhary is a trained barrister-at-law and an advocate in Delhi.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of THE WEEK.