"When a woman is raped by a stranger, she has to live with a frightening memory. When she is raped by her husband, she has to live with the rapist.”

- David Finkelhor and Kersti Yllo

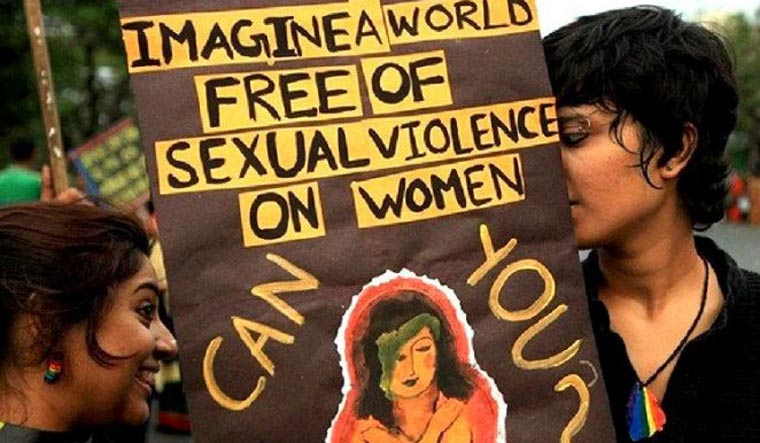

Women activists and anti-rape campaigners will have their fingers crossed as the Supreme Court is all set to examine the constitutional validity of marital rape exception in the second week of January. The decades-old debate on removing the contentious provision that allows a man to force himself on his wife without her consent was earlier revived by a split verdict of the Delhi High Court in May 2022 and further resuscitated by the apex court's significant observations on the abortion law in September.

Though the rape laws in India have undergone several amendments since Independence, spousal rape exception remains unchanged due to various factors, mainly political apathy and legal quandary. According to National Family Health Survey 5, nearly one in three women aged between 18 and 49 have suffered some form of spousal abuse, and around six per cent have suffered sexual violence. Among married women who have experienced sexual abuse, 83 per cent report their current husband and 13 per cent report a former husband as the perpetrator. This would essentially mean thousands of women in the country live with their potential rapists.

Rights activists and libbers term the exception provision in rape law as violative of women's dignity and bodily privacy, and argue that since the essence of the very definition of rape lies with the 'consent' of woman, a wife should not be denied that privilege. However, India, despite being a fast-growing democratic republic and a potential superpower, has so far stalled any legislative business in this regard, thanks to its archaic social construct mired in deep-rooted patriarchy, caste and religion.

The legal conundrum

Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code defines rape as “sexual intercourse with a woman against her will, without her consent, by coercion, misrepresentation or fraud or at a time when she has been intoxicated or duped or is of unsound mental health and in any case if she is under 18 years of age”. However, exception 2 of this section states that sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under 18 years of age, is not rape.

A batch of petitions has been filed in the Supreme Court after the Delhi High Court pronounced a split verdict on the issue in May 2022. While Justice Rajiv Shakdher held that the immunity to husband from the offence of marital rape was unconstitutional, Justice C. Hari Shankar was of the view that it did not violate the Constitution since the exception was based on an intelligible differentia. The apex court is likely to start hearing the pleas this month.

In its first affidavit filed in the Delhi High Court in 2017, the Union government had vehemently opposed criminalisation of marital rape, saying it could have a “destabilising effect on the institution of marriage” and become an “easy tool for harassing husbands”. The government was also worried about what evidences the courts will rely upon in such circumstances as there can be no lasting evidence in case of sexual acts between a man and his own wife. The affidavit further quoted the Law Commission's 172nd report in 2000, which had not favoured the demand for striking down the exception clause, saying it may lead to “excessive interference” with marital relationship and destroy the “institution of marriage”.

In early 2022, the government filed a fresh affidavit in the high court, claiming that the issue has a major social impact, so a meaningful consultative process with various stakeholders and state governments must be done as it “cannot be decided merely upon the argument of a few lawyers”.

So, what are the options available for a woman who wants legal recourse after being subjected to sexual violence by her husband? “In case the woman wants her marriage to subsist but the sexual violence to ebb, she has the option of resorting to the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, in which she has the right to approach the police station directly and register a complaint, or file a complaint to a Protection Officer or Service Provider, or go to court,” Charu Wali Khanna, a leading women's rights lawyer and former member of the National Commission for Women, told THE WEEK.

"The Act gives a very expansive definition to the term 'domestic violence' and includes sexual abuse as a form of violence. It provides a number of reliefs ranging from counselling of both parties and monetary compensation to protection order restraining respondent from committing the act of violence. All in the hope of enabling the woman lead a peaceful marital life,” says Khanna. She adds that Section 31 of this Act, however, provides for penalty for breach of protection order by respondent, which includes imprisonment or fine.

If the woman wants her husband punished in the first instance itself, she has the option to use alternate route of criminal action against him under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code, she further says.

However, there are many who believe the Domestic Violence Act is not a reasonable substitute to a law on marital rape. “The DV Act provides civil remedies such as protection orders, maintenance order, residence order and so on. But getting an order is not an easy process. It takes a long time and men easily violate protection orders or other orders issued by the court,” Shalu Nigam, an eminent lawyer and human rights activist, told THE WEEK.

She alleges that the law is weaponised by resourceful men who file SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public participation) against women. “They file application for restitution of conjugal rights, divorce applications, custody suits, application for visitation rights and so on. Frequently, the courts protect or save the families but are not concerned about safety of women and children in the violent homes. Courts, many times, force women to go back to violent homes in their zeal to save families,” Nigam, who has done extensive research on the DV Act in India, says, adding that the mindset needs to change.

In 2013, the J.S. Verma Committee formed in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya gang-rape in Delhi, had recommended making marital rape a criminal offence. “The law ought to specify that marital or other relationship between the perpetrator or victim is not a valid defence against the crimes of rape or sexual violation,” Verma had written unequivocally in his report. However, the recommendations were not included in the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act passed in the same year after a Parliament Standing Committee on Home Affairs maintained that the “entire family system will be under great stress” if marital rape was criminalised.

The Pam Rajput Committee, set up by the then Manmohan Singh government in 2012 to study the status of women in India, too, had recommended criminalisation of rape within marriage. The committee report, submitted to the Women and Child Development Ministry in 2015, was also critical of the Criminal Laws (Amendment) Act 2013 for keeping spousal rape out of its ambit. “This shows the legislature’s failure to appreciate the growing menace of this crime wherein the victim has to suffer on a daily basis,” the panel observed.

Various high courts had taken up the issue at different times. The Gujarat High Court in 2018 and the Chhattisgarh High Court in 2021 ruled that a husband cannot be prosecuted for forcing himself on his wife. Justice J.B. Pardiwala of Gujarat High Court, however, made some significant observations as he said the law that does not give married and unmarried women equal protection creates conditions that lead to marital rape. “It allows men and women to believe that raping wife is acceptable. Making rape of a wife illegal will remove such destructive attitude that promotes marital rape,” Justice Pardiwala wrote in his verdict.

The Kerala High Court delivered a landmark verdict in 2021 when it ruled that marital rape is a solid ground for divorce. Justices Muhamed Mustaque and Kauser Edappagath said a woman’s body is not a possession of her husband and that the husband does not have special or additional privileges and rights in a conjugal relationship.

On March 23, 2022, the Karnataka High Court held that a man can be prosecuted for raping his wife and the exception granted to the husband under Section 375 of the IPC cannot be “absolute”. "The institution of marriage does not confer, cannot confer and should not be construed to confer, any special male privilege or a licence for unleashing of a brutal beast," said Justice M. Nagaprasanna in what could have been a groundbreaking verdict. The Supreme Court, however, stayed this order.

The top court, meanwhile, made some significant observations in September 2022, when it held that forceful pregnancy of a married woman can be treated as marital rape. “Under the MTP Act, rapes shall also include marital rape… Sexual assault by husbands can take a form of rape,” Justice D.Y. Chandrachud categorically said in his ruling, just a month before he was appointed the Chief Justice of India. Though the court's observation came purely within the ambit of abortion, it has given good grounds for women activists for expecting a favourable verdict in case of marital rape, too.

Political dilemma

In both the affidavits filed in the Delhi High Court, the government obliquely admits that sexual violence within marriage is undeniably common in India, but it is more concerned about the moral ramifications and possible “misuse” in case the legal immunity to husbands is done away with.

Nigam, however, argues that the state's obligation is to promote the rights of woman rather than protecting the institution of marriage. She says a woman as a citizen is legally under no obligation to pay the price through risking her health or life to save her family.

“Why the male-dominated courts and governments are infantilizing women and depriving them of their choice and agency? Women are burdened with all household work; they manage children, take care of the sick and the elderly and do all other work. Then why can't they take decisions about their bodies?,” she asks.

In 2013, the United Nations Committee on Elimination of Discrimination Against Women had urged all its member countries, including India, to criminalise rape within the wedlock. However, both the Congress and the BJP—the two parties which led the successive governments at the Centre—have been largely skeptical on outlawing rape within marriage, though individual voices were raised at times in favour of it. The parliament panel which opposed the Verma Committee report had members of both the parties; in fact, BJP leader M. Venkaiah Naidu was its chairman. CPI MP D. Raja was the sole member to raise a dissenting voice.

Maneka Gandhi, who was the women and child development minister in the first Narendra Modi government, was ambiguous in her stand. “The concept of marital rape, as understood internationally, cannot be suitably applied in the Indian context due to various factors like level of education or illiteracy, poverty, myriad social customs and values, religious beliefs, mindset of the society to treat the marriage as a sacrament etc,” Gandhi told Parliament in 2016. Her statement was clearly at variance with her previous stand that violence against women shouldn’t be limited to violence by strangers.

Gandhi's successor Smriti Irani last year told Parliament that the government had already started the process of comprehensive amendments to criminal laws. She, however, was quick to warn against condemning every man as a rapist and every marriage as a violent one.

The Aam Admi Party government in Delhi has also taken a stand against criminalisation of marital rape, saying it is already an offence under section 498A of Indian Penal Code, which deals with husband subjecting wife to cruelty. The Arvind Kejriwal government was of the opinion that rape within marriage is "not a violation" of Article 21 of the Constitution as a wife is not compelled to live with a sexually abusive husband under personal law.

DMK MP Kanimozhi in 2014, Congress's Avinash Pandey in 2015 and Shashi Tharoor in 2019 had proposed separate private member bills in Rajya Sabha seeking removal of the exemption clause in rape law. However, all these bills failed to garner enough support of members. During the just concluded winter session, Trinamool Congress MP Derek O'Brien moved a similar bill, which also met with the same fate.

The CPI and the CPI(M) have been vociferous in their demand for revoking marital rape immunity. However, sensing its cultural and moral undertones, most parties have either chosen to remain silent or taken a vague stand over the years.

The BJP government in Karnataka, however, caught many on the hop in December 2022 by filing an affidavit in the Supreme Court supporting the prosecution of a man accused of raping his wife. The government also defended the March 23 judgment of the high court which had declined to quash the charge of rape framed against the accused.

Will India come out of the hall of shame which it shares with 30-odd countries? All eyes are now set on the apex court.