Oncologists will describe their work as revolutionary, bringing about what is said to be a "paradigm shift" in the treatment of cancer. As scientists across the world grapple to find that elusive cure for the disease—one that has, for long, been seen as a death sentence for those afflicted with—two researchers have won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on immunotherapy.

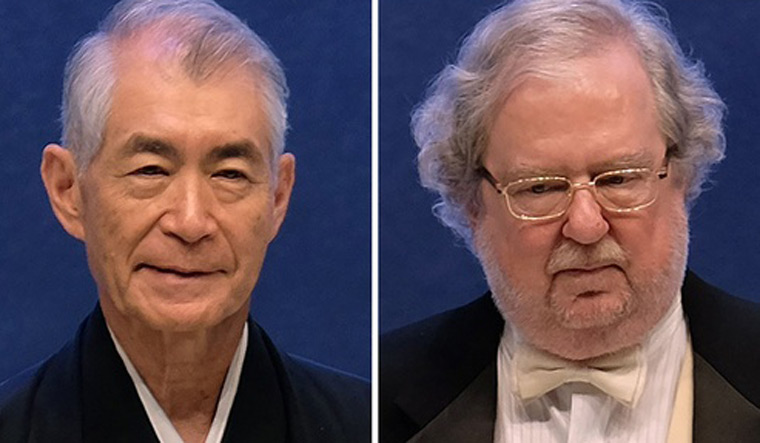

This year, the prize has gone to James P. Allison, PhD, chair of Immunology and executive director of the Immunotherapy Platform at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Centre, and Tasuku Honjo, MD, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan. The two have been awarded for their work on immunotherapy, a form of therapy that trains the immune system to attack the cancer cells.

What conventional therapy in cancer treatment—radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery—does is to attack the tumour. In the process, though, healthy cells also take a hit. With immunotherapy, however, experts have found a way to prep the immune system, the body's natural defense mechanism, in a way that it is capable of attacking the cancer cells only.

It is a task that the body's immune system does anyway—protecting the body against "invaders". In cancer, however, something else happens in the body. The cancer cells trick, even weaken the immune system's army of soldiers, especially T cells (T cell, or T lymphocyte, is a type of lymphocyte—a subtype of white blood cell—that plays a central role in cell-mediated immunity). Immunotherapy strengthens the body's army of soldiers by several means, allowing it to kill the cancer cells.

According to the Nobel committee, Allison studied a known protein that functions as a brake on the immune system. He realised the potential of releasing the brake and thereby unleashing our immune cells to attack tumors. He then developed this concept into a brand new approach for treating patients.

In parallel, Honjo discovered a protein on immune cells, and after careful exploration of its function, eventually revealed that it also operates as a brake, but with a different mechanism of action. Therapies based on his discovery proved to be strikingly effective in the fight against cancer.

“By stimulating the ability of our immune system to attack tumor cells, this year’s Nobel Prize laureates have established an entirely new principle for cancer therapy,” the Nobel Assembly of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm said while announcing the award for Allison and Honjo.

“I’m honored and humbled to receive this prestigious recognition,” Allison said in a statement released by the MD Anderson Cancer Centre. “A driving motivation for scientists is simply to push the frontiers of knowledge. I didn’t set out to study cancer, but to understand the biology of T cells, these incredible cells that travel our bodies and work to protect us.”

According to the Centre, the prize recognises Allison’s "basic science discoveries on the biology of T cells, the adaptive immune system’s soldiers, and his invention of immune checkpoint blockade to treat cancer". His crucial insight was to block a protein on T cells (CTLA-4) that acts as a brake on their activation, freeing the T cells to attack cancer.

Allison developed an antibody to block the checkpoint protein CTLA-4 and his work led to the development of the first immune checkpoint inhibitor drug. Ipilimumab was approved for late-stage melanoma by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2011.

The drug became the first to extend the survival of patients with late-stage melanoma (skin cancer). Follow-up studies show 20 per cent of those treated live for at least three years with many living for 10 years and beyond.

Honjo discovered PD-1, another protein expressed on the surface of T cells. Honjo explored its function in a series of experiments performed over many years in his laboratory at Kyoto University. The results showed that PD-1, similar to CTLA-4, functions as a T cell brake. In animal experiments, PD-1 blockade was also shown to be a promising strategy in the fight against cancer, as demonstrated by Honjo and other groups. This paved the way for utilising PD-1 as a target in the treatment of patients. Clinical development ensued, and in 2012 a key study demonstrated clear efficacy in the treatment of patients with different types of cancer. Results were dramatic, leading to long-term remission and possible cure in several patients with metastatic cancer, a condition that had previously been considered untreatable.

After the initial studies showing the effects of CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade, the clinical development has been dramatic. However, similar to other cancer therapies, adverse side effects are also seen in immunotherapy. They are caused by an overactive immune response, leading to autoimmune reactions, but are usually manageable. Intense continuing research is focused on elucidating mechanisms of action, with the aim of improving therapies and reducing side effects.

According to the Nobel committee, of the two treatment strategies, Honjo's checkpoint therapy against PD-1 has proven "more effective and positive results are being observed in several types of cancer, including lung cancer, renal cancer, lymphoma and melanoma". New clinical studies indicate that combination therapy, targeting both CTLA-4 and PD-1, can be even more effective, as demonstrated in patients with melanoma.

“When it comes to cancers that are more aggressive, in late stages, and in solid tumours such as lung cancer, oesophageal cancer, liver and brain, we have reached a plateau in cancer treatments,” Dr Rakesh Jalali, medical director, Apollo Proton Cancer Centre, Chennai had told THE WEEK in an interview earlier this year. “In the last five to ten years, however, immunotherapy has ushered in a new revolution,” he said.

For those who don’t have an option, for whom all conventional treatments have failed, immunotherapy is a “real breakthrough” treatment, said Jalali.

However, in India, doctors such as Jalali also say that the immunotherapy drugs are expensive, and out of bounds for a large section of the population. Experts also warn that the therapy is not a "magic wand" and not every patient will respond to the treatment. But everyone agrees that the therapy holds much promise in the future of cancer treatment.