Many political scientists argue that the military, often the only organised institution in nations with fledgling political infrastructures, can supplant ill-trained politicians and ensure stability. But history is also replete with examples of the military's dismal failures in building lasting governing structures. Politicians, on the contrary, offer credible alternatives, even though many of them carry autocratic genes in their bones.

In Bangladesh's case, the nation's first chief justice, Abusadat Mohammad Sayem, who became the first chief martial law administrator in 1975 trampling upon the very constitution he had sworn to uphold, acknowledged this truism. When General Ziaur Rahman, who became Bangladesh's first military president, pushed him out of the Bangabhavan, the presidential palace, the frail bespectacled jurist whom a U.S. diplomat once described as “timid to boot,” found no legs to stand on.

“If you are a politician,” Sayem explained to me during an interview, “your source of power is people; if you are a general, your source of power is the military. What was I? Neither a politician nor a military man. So when the military wanted their man in power, I had to leave.”

Even though Zia, as General Ziaur Rahman was popularly called, rode the black horse of the military to enter the presidential palace through the back door, he too soon realised that his future lay with people, not with the soldiers. As an instrument of politics, he quickly learned, the military was treacherous and unreliable. Still, the Bangladeshi military again felt an inner urge to appear as the nation's saviour just a decade after General H.M. Ershad was forced out by a popular upsurge. General Nooruddin Khan's attempt in 2004 failed in the face of stiff opposition, especially from U.S. Ambassador Harry Thomas. But in their adventure in 2007, the generals found a group of civilians waiting eagerly to extend a helping hand.

Misguided Civil Society

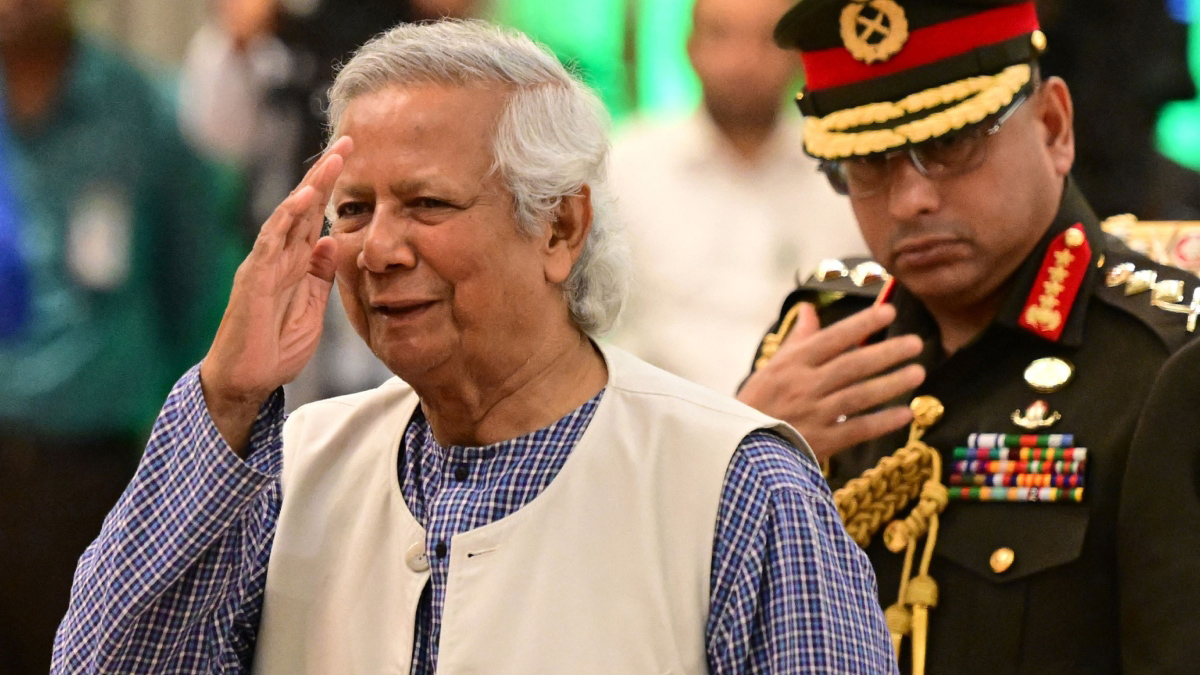

In early 2006, [Muhammad] Yunus started a campaign for honest and clean candidates in national elections. He did this with support from members of the so-called civil society clique, including Professor Rehman Sobhan, former Justice Habibur Rahman, former Foreign Minister Kamal Hossain, journalists Matiur Rahman of Prothom Alo and Mahfuz Anam of The Daily Star as well as economist Debapriya Bhattchariya of the Centre for Policy Dialogue, a policy research group in Dhaka.

Despite having considerable knowledge of General Ayub Khan's failed experiment in the 1960s with his top-down political setup in Pakistan, this misguided clique embarked upon reinventing the wheel using the Nobel laureate. This gang ignored the truism that military-backed regimes never provided a durable solution. Every attempt, from Ayub to Ershad, who ruled Bangladesh during 1980s and early 1990s, ended in dismal failures, with disastrous consequences for the country. Still, they encouraged Yunus to plunge into politics with blessings from the cantonment.

On February 4, 2006, the microfinance pioneer proposed that political parties chose a respected citizen to resolve the deadlock over holding the next general elections.

Speaking at a dinner marking the birthday of The Daily Star, Bangladesh's leading English daily edited by Mahfuz Anam, Yunus noted that even though the interim administration was not constitutionally obliged to meet opposition demands to change the Election Commission and transitional caretaker government set-ups, there was a national interest in ending the controversy and focusing constructively on the next election. Yunus revealed he would consider entering politics in the latter part of that year.

Political has-beens in Bangladesh talked about a solution based on the formula adopted by former Pakistani military ruler General Parvez Musharraf in the hope of riding the military's coattails to power. Some Awami League supporters muttered about a military takeover to hype the extremist threat and because of their obsession with ousting Zia at any cost. However, there was no evidence that such talk was anything more than motivated tea-time chatter.

Neither the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, led by former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia nor the Awami League, headed by just-ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, had formally reacted to Yunus’s proposal. However, media and civil society members responded positively. The proposal recognised the need to find a new formula to ensure fair elections and thus went against the government assertion that the existing institutions were adequate to ensure fair polls. Awami League leaders would not publicly endorse Yunus’s proposal before ensuring that it would benefit them. Leaders of smaller parties, including Gono Forum, led by Kamal Hossain, a former foreign minister, and Bikalpa Dhara Bangladesh, headed by former President Badruddoza Chowhdhury, hailed the plan.

The Awami League finally decided to hit back. Two weeks after the president imposed the emergency rule, retired Major General Tarique Ahmed Siddique, head of Hasina's security, prepared a one-page interim government “work schedule.” He created the document after his military contacts, who were opposed to a prolonged military involvement in the government, showed him a three-page strategy paper. The military strategy outlined lofty goals and a long-term government of national unity. The existence of the military strategy paper proposing a long-term interim government was consistent with mounting evidence that the military, the clear power behind the throne, envisaged a much broader agenda and time-frame than just preparing the country for elections as soon as possible. This path clearly went against the Awami League's idea. Countering the military blueprint, Hasina demanded early parliamentary elections. She wanted the interim administration to finish updating the voter list to hold elections on April 3, 2007.

Chiefs in Tight Spot

The three military service chiefs were anxious about their role behind the throne. They did not wish to overstay their welcome. They were uncomfortable in the situation in which they found themselves. There were differences between the military and the civilian advisers on several matters, especially on press controls and whether to grant bail to detained corruption suspects.

To implement the regime's goal to get rid of corrupt politicians, during the night of March 7, 2007 police made near simultaneous midnight arrests of Tarique Rahman, Zia's son, her former Health Minister Dr Khandaker Mosharraf Hossain, and Awami League-allied Chittagong City Mayor ABM Mohiuddin Chowdhury. Also arrested were Jamaat-e-Islami former parliament member Dr Syed Abdullah Mohammad Taher and Atiquallah Khan Masud, editor of the daily Bangla language newspaper Janakantha.

Later, joint military and police forces went twice to Hasina's house to search for Awami League members, including some relatives of Hasina. Hasina's security chief, Tarique Siddique, refused entrance of the joint forces who were dressed in civilian clothes, after conferring with the Army's 9th Division's commander. The commander, General Masud Chowdhury, professed ignorance about the raid on Hasina's house. An hour later, the forces returned, threatened to break the doors and Siddique let them in. He, in the meantime, heard that Tarique, Khaleda Zia's elder son and BNP de facto chief, had been arrested and took the Sudha Sadan, Hasina's private residence, raid as “balancing things for the arrest of Tarique.” The joint forces left Sudha Sadan without arresting anyone.

On March 8, local news media published a list of fifty political leaders and businessmen who would be the subject of the second phase of the government's anti-corruption drive. The list included Sigma Huda, former Communications Minister Nazmul Huda's wife, garment factory owner A.K. Azad, who was also president of the Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce and Industries, Awami League Religion Adviser Sheikh Abdullah, and Zia's younger brother, Biman airlines flight engineer Shamim Eskander.

One of the listed individuals, Jatiya Party chief Anwar Hossain Monju, owner of the Bengali Daily Ittefaq, told a U.S. diplomat that after police raided his house asking for his whereabouts, he did not return home fearing arrest. He was willing to have his representative file any statement of his assets the Anti-Corruption Commission wanted, but afraid to file it personally. He claimed that in February several prominent businessmen were arrested immediately after they had filed their statements to the commission.

Initial public reaction to the arrest of Tarique was overwhelmingly positive. Nonetheless, the government's continued targeting of high profile political and business leaders alarmed elites. Anisul Haque, former president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Export Association, expressed concern over the arrests. He told the government that the fear of arrest of businessmen undermined business confidence among businessmen, a fallout that would ultimately hurt the economy.

While the regime pursued corruption allegations against the two ladies, the nation's military spy agency DGFI's boss General Fazlul Bari continued to recruit for a new political organisation — the “King's Party.” As many as 100 BNP leaders, mostly members of the past parliament, had given him undated letters of resignation to position themselves for joining the new party. The government orchestrated a three-pronged assault — court cases, a new party, and party reform initiatives — to force the two grand dames of Bangladeshi politics to step aside. BNP's Mannan Bhuiyan would not act without a military nod, so the military intelligence unit got intimately tied to the new party.

The regime's initial ban on political demonstrations and outdoor political gatherings or protests was later expanded to include all political activity. The ban prevented the parties from beginning the process of internal political reform and had stifled consultations on election reforms.

Move to Oust Khaleda

Within in less than three months, after the military-backed government came to power, dissidents in both parties went public with reform proposals. BNP's Mannan Bhuiyan cooked up a coup against Zia. He spearheaded a move for her to resign and inject more collective decision-making into the party. He began an ambitious plan to take over the leadership of his party once the military forced Zia to leave Bangladesh.

Soon after the promulgation of the state of emergency, the military asked Zia to send her son Tarique abroad and clean up her party, so she could still lead the country. Zia initially agreed, but later shifted her stand. She became angry when Bhuiyan advised her to comply with the military's request. By the time she finally figured out no countercoup was in sight to save her, the military's stance had hardened.

Bhuiyan envisioned a national government with representatives from different political parties to replace the interim regime. Kamal Hossain and Yunus could be part of this government. The military, on the contrary, wanted to create the King's Party with deserters from various political organisations, including the BNP and the Awami League. Bhuiyan opposed the military's idea to create a new party. Instead, he wanted the military to help the parties reform themselves and allow the one that won a free and fair election to form the government. Although he opposed the military idea to give birth to a new political group, Bhuiyan kept mum about Army chief General Moeen's desire to become president after his term expired.

Zia's critics within the BNP, despite their unhappiness with the boss, differed on whether Bhuiyan was the person to lead the party after her departure. His reluctance to challenge Zia face to face, leaving it to others to clean up the field for him, underscored why internal reform for the BNP, or the Awami League for that matter, had always been so difficult.

Meanwhile, Hasina left Bangladesh for the United States. The timing of Hasina's departure, just days before her father's high-profile birthday anniversary, fuelled speculation that she was forced by the military to go into exile and increased the pressure on Zia to follow suit. Zia was ready to leave Bangladesh, provided her exile, probably in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, was guaranteed to be comfortable.

If Zia left and Hasina, who was already in the United States purportedly for medical treatment, stayed away, the era of the “two ladies” would finally end. As speculation mounted that Hasina's visit to America would turn out to be much longer than advertised, BNP leaders told U.S. diplomats that Zia was finished and must leave Bangladesh. Four former ministers separately reported that her departure was imminent, and two claimed to be involved with or privy to the DGFI negotiations with Zia.

Zia had agreed to leave, provided her sons, Tarique and Koko, and perhaps other relatives, were allowed to go with her. Tarique was in custody. He already faced one extortion charge relating to a party nomination for the last election. Koko — the lower profile younger brother of Tarique — was free, but on an unofficial list of 50 corrupt persons facing government scrutiny pressure. Former Home State Minister Babar told the U.S. ambassador that the deal called for Zia to travel without Tarique, but Tarique would be released to seek medical treatment abroad and would not return.

Zia preferred Jeddah as a refuge. She sought assurances she would live there in appropriate comfort. Under virtual house arrest in her cantonment residence, with the landlines cut off and visitors having to secure military permission to enter the premises, she occasionally ventured out, but rarely made a public appearance.

Even Zia loyalists, such as former Finance Minister Saifur Rahman, wanted Zia to go. They had all along warned her to act against corruption and party thugs associated with Tarique. As many as one quarter of the party's former parliament members were ready to support Bhuiyan as new party leader. He, however, was unable or unwilling to openly challenge Zia. Bhuiyan wanted to wait until Zia left Bangladesh. Because of the anti-corruption campaign's wide net, he had no serious rival within the party.

In contrast to their BNP opposites, Awami League officials continued to toe the party line that she would soon return home. They appreciated that the military-backed regime's reform agenda found its roots in long-standing opposition demands. They insisted that prolonged criticism of Hasina at a party forum constituted reform and signalled openness to change. However, they equivocated if she would submit her leadership to the vote of the appropriate party council.

BNP sources with good military and intelligence contacts claimed that Hasina was being blackmailed with evidence that she took money from both Indian and Pakistani intelligence agencies; even if Hasina was a free actor, it took great courage for her to return to Bangladesh from the United States under these circumstances. The incentive for the military to send Tarique overseas was tremendous because, as General Zia's son, he retained the ability to rally support among Zia loyalists as long as he was alive or in the country.

(This is an excerpt from B.Z. Khasru's upcoming book, One Eleven, Minus Two, Prime Minister Hasina's War on Yunus and America, which will be published shortly by Rupa Publications, New Delhi.)

B. Z. Khasru, a U.S.-based journalist, is the author of Myths and Facts Bangladesh Liberation War: How India, U.S., China and USSR Shaped the Outcome, and The Bangladesh Military Coup and the CIA Link