It usually takes the third generation of a displaced community to start asking about its roots, says Amardeep Singh (50). “In my case, however, the tug came into the second generation itself,’’ he said. Singh's father was a Sikh who had to leave his lands in Muzaffarabad (now PoK) and move to Gorakhpur after partition. His father's misty-eyed memories of home affected Singh majorly, and by the time he was 18, he was avidly lapping up everything about the history of Kashmir, Punjab, Afghanistan, and yes, of the Sikhs.

A Sikh himself, Singh marvels at the mighty empire of Ranjit Singh, the last empire that the British claimed in India. “It spread from the borders of Afghanistan right up to Punjab in India,” he said, “But, 80 per cent of that mighty empire is in present-day Pakistan. A rich legacy and heritage that is fading away, and to which a majority of the Sikhs have absolutely no connection.”

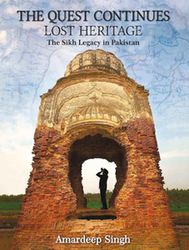

These emotions made Singh take two amazing trips into the interiors of Pakistan (itself a wonder, given the strict visa regimes) and return with a trove of pictures and stories, which he has made into two huge books. The first one, Lost Heritage: The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan, was released in 2016 by former Pakistani high commissioner to India, Abdul Basit. The sequel, The Quest Continues, was released recently.

Singh's lens capture both the fading legacy as well as an unvanquished, vibrant one, which evolves, but retains its ancient essence. There is a lament in the pictures which catalogue gurdwaras that were converted to schools, or taken over as residence by poor migrants from East Pakistan.

There's wonderment as his pictures zoom into the cenotaph of the Sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa at Jamrud Fort, now under the Pakistan army. Nalwa was a mighty warrior who helped extend the Sikh empire right up to the Khyber Pass. Nalwa's valour has immense resonance in Sikh homes, but there's barely a tangible link left for them post partition.

The picture of the court-martialled gates of Shabqadar Fort brings legend to life. Maharaja Sher Singh had, in 1840, sentenced the gates to 100 years imprisonment for having been unable to defend an attack of Afghan mercenaries. The gates were punished because the king felt his general, who should have got the rap, was too valuable to be punished. The gates remained chained well over a century after their sentence was served.

The visit to Thoha Khalsa was painful. It's a place which brings alive all the savagery of partition. There's a well in a field there, known now as the place into which nearly 75 women jumped and died to escape a worse fate. Meeting the sons of one of those women who chose to live instead, and convert to the faith of the man she married, was emotional for both the author and the descendant.

Singh says that while his lens is the Sikh legacy, he has actually captured the Punjab legacy, which was a syncretic and secular one. “Today's Sikhs go for pilgrim to certain shrines in Pakistan, but so much of their cultural and military history exists beyond the border. It is fading from our consciousness. My attempt was to chronicle it before it changes further.''

Singh also noticed that beyond the political rhetoric, there's a friendliness and warm hospitality across the border, and a deep sense of a shared past.

The Quest Continues: Lost

heritage, the Sikh Legacy in Pakistan

By Amardeep Singh

Published by: Himalayan Books

Pages: 491; Price: Rs 6,000