In 1948, when Donald Anderson was about 14 years old, he went on a hunting trip to Javalagiri in Tamil Nadu, with his brother-in-law Jack and friend Sydney D’Silva. They left Jack at camp and went to explore the jungle. After seeing a cow that had been killed by a tiger, they stayed back to bag the tiger when it returned to the kill. Excited by the prospect of bagging their first tiger, they created a temporary shelter with some branches and settled in for the night. Don nodded off. In the middle of the night, the sound of a soft growl woke him up. They were sitting in a precarious position facing the dead cow. What if the tiger attacked from behind? Sydney looked terribly scared and began to shake. Don squeezed his shoulders reassuringly, but his friend only started shaking more. To his horror, he realised Sydney was about to scream. Don slammed his hand over Sydney’s mouth to stifle the sound, holding the rifle tight with the other hand. That is when it happened: Sydney pushed his hand away and collapsed in laughter. Apparently, the growl was from Sydney’s stomach as he hadn’t eaten for a long time. His seizure was nothing but suppressed laughter. The tiger, probably disgusted with the sight of two giggling teenagers emerging from the bushes, never returned that night.

The Last White Hunter is full of jungle stories like this, sparkling with humour and excitement. Not all of them are funny. There are some terrifying experiences, like when Don was nearly killed by a charging bull elephant. He was stalking it through a game path and they saw each other almost at the same time. It curled in its trunk between its tusks and with eyes filled with rage, attacked. Don’s gun was loaded only with soft-nosed bullets, used for shooting deer, panthers and tigers, so he knew that a frontal head shot would not do. At the last minute, he did something that he admits he was not proud of—he aimed at the elephant’s left front leg and fired, stopping it in its tracks. Then there was the time his tracker Kuppa was killed by a panther and he had to helplessly watch the animal mauling him because he knew that if he shot, he was sure to hit Kuppa.

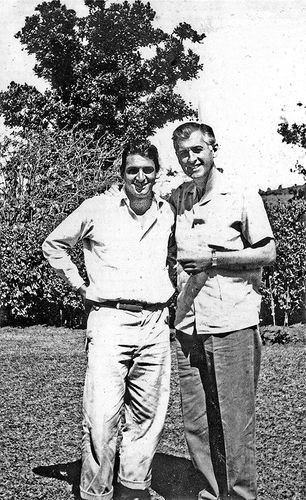

The jungle played an important role in Don’s life, but it was not his only love. He was also a bit of a Casanova, romancing many women at the same time. He claims he had no trouble landing women, something I am tempted to believe if he looked half as good as he does in photographs from his younger days. His childhood in Prospect House in Bengaluru, the pranks he played in school and rendezvous with friends in places like 3 Aces Club on MG Road and Crown Bakery near Catholic Club are described in great detail.

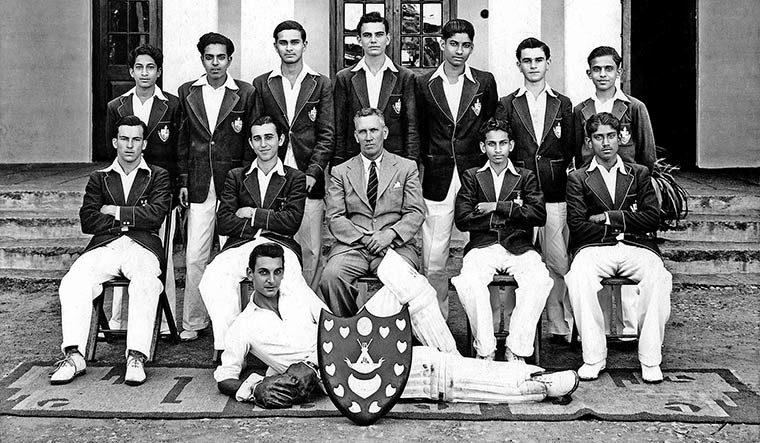

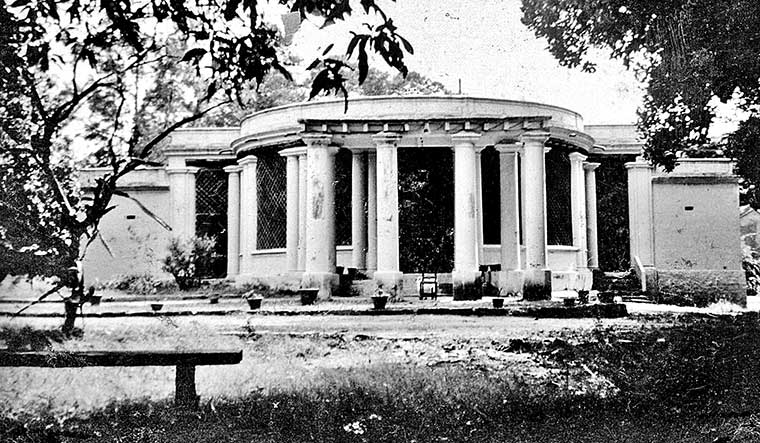

Don is probably most famous for being the son of Kenneth Anderson, who is sometimes referred to as the Jim Corbett of the south. Kenneth has written eight books on his adventures in the jungle. Don describes his dad as brilliant—a master chess player, a voracious reader and an overachiever in school. He also claimed to be an inventor; his kitty included a cure for baldness (hibiscus flowers!) and a pair of spectacles to look at people’s auras. When his family made fun of his inventions, he would quote a verse from the Bible: “No prophet is accepted in his own hometown.” But Kenneth’s true passion lay in the animal world. He had an uncanny ability to communicate with all sorts of animals, who would flock to him wherever he went. Don admits he was never academically oriented like his father, but he did inherit his father’s love for nature and the jungle. When he was young, Don and his father had a turbulent relationship, as his erudite sister June was the apple of his father’s eye. But, later, they became close and would go on hunting trips together. When he was dying of cancer, his last words to Don were: “You’ve been a brick, Don. You’re my everything.” After his parents’ death, Don fell into depression, lost all his properties, and spent his last days in penury.

The writer, Joshua Mathew, was part of a Kenneth Anderson fan club in Bengaluru and that is how he came to hear that Kenneth’s son was still alive. Although Mathew went to meet him in 2003—when he was living as a recluse in the outhouse of a building on No 10 Serpentine Street, Bengaluru—Don refused to talk to him. Mathew was rejected two more times, but got a window of opportunity in 2008, when one of the members of the club contributed to the payment of Don’s hospital bill after a surgery at Santosh Nursing Home. A few weeks later, the group trooped to Don’s home, and Don, in turn, found a captive audience to listen to his stories. They soon forged a routine, where in return for his time and entertainment, they would take him around in their cars and buy meals and medicines for him. “He depended a lot on me to do things for him,” says Mathew. “He would insist on repaying me, but what he considered was of equal value, was usually rubbish [for which I would have no use].”

Mathew describes Don as a “fighter to the very end, fighting poverty, depression and illness without complaining”. The best thing about The Last White Hunter is that it is narrated honestly, laying bare the facts of Don’s life without embroidering the truth, because the truth needed no embroidery. Don died at the age of 80 in 2014. He was still living in the tiny room at No 10 Serpentine Street, despite several attempts by the landlady to evict him. It was a terrible fall from grace for the man who grew up in a large bungalow with many bedrooms and servants to take care of him, but he preferred the outhouse to some apartment hundreds of feet above the ground. “Imagine not being able to walk on grass or smell the wet earth after the rain,” he says in the book. “Imagine not being able to hear a ripe mango fall or the last drops of rain trickling into a puddle. I would rather die than live a day knowing I could never experience those things again.”

The Last White Hunter

By Donald Anderson with Joshua Mathew

Published by Indus Source Books

Pages 264; price Rs 650