WHO WOULDN’T WANT to be like Anil Ambani! One of the richest Indians, he is married to an erstwhile movie star, and is the toast of the A-list social circuit.

Would you really want to be like Anil Ambani? His wealth may seem impressive at a reported $1.2 billion; but he was ten times richer just about a decade ago. There is a plethora of cases against him and his companies, filed by corporate clients to banks to ministries. On February 20, the Supreme Court shocked India Inc by holding Ambani guilty of contempt of court, just a few days after he took his flagship telecom company, Reliance Communications (RCom), into bankruptcy courts. The court gave him four weeks to pay up the due of Rs453 crore to the Swedish telecom company Ericsson, or go to jail.

The past several months have not been good for Ambani; yet the court conviction was an especially hard blow. He was refused exemption from appearing in the court. Many people thought he would immediately pay up and move on with the pressing task of rescuing his crises-ridden company. Surprisingly, he has not done that (other than the Rs118 crore he deposited earlier as part payment) even three weeks after the Supreme Court direction.

Many of his businesses, and corporate assets, are now tied up in courts and by the lenders. His companies owe the lenders some Rs40,000 crore. His lenders, led by State Bank of India, now have a say in all his financial moves, and it is said that they have not always been helpful in his efforts to raise funds. Some other creditors, like HSBC Daisy Investments, have now approached the Supreme Court demanding their dues. Ambani, meanwhile, has filed cases against Edelweiss and L&T Finance for selling pledged shares; Edelweiss has returned the favour with a defamation notice.

Perhaps worse for Ambani than the rap on the knuckles by the court would have been the bloody hit his company stocks took as news spread. Shares of RCom fell almost 10 per cent after the Supreme Court verdict, while other group companies closed up to 4.26 per cent lower at the Bombay Stock Exchange. RCom has lost 95 per cent of its valuation since 2006.

For Ambani, the Ericsson case was initially just a small irritant, considering his growing litany of woes. After parting ways with his brother, Mukesh, many business gambles he took did not pan out the way he wanted them to. Acquiring spectrum for 3G services (3G was short-lived as 4G took over), operating in many circles, betting on CDMA technology (even as rival GSM became the global standard), all turned out to be disasters. These were all funded by expensive borrowings, leading to debt piling up.

Expanding into other areas, like multiplex, filmmaking, radio and television also mostly came a cropper. Reliance Infra, which operated Delhi Metro’s Airport Express Line, pulled out after a while as it failed to make profits.

In 2010, the Ambani brothers decided to cooperate again, despite the bitter fight they had over their father’s empire. A no-competition agreement between them, which had kept either out of sectors the other was present in, was rescinded. It turned out to be a body blow for Anil, as Mukesh ventured into telecom. With an aggressive pricing strategy, Mukesh’s Reliance Jio made a huge dent on the customer base and revenues of all existing telecom players. RCom was the worst hit. Once the second largest mobile operator in India, it stopped consumer operations in 2017.

“Telecom is an extremely tough segment to make sustainable profits in, and with Jio entering, it has only become tougher,” says N. Chandramouli, industry analyst and CEO of TRA Research. “RCom was sitting on a great opportunity at one point of time. However, now it has turned into a burden.”

The way out of the quagmire for Ambani lies in the huge assets that he holds. Mukesh’s Jio has promised to buy out RCom’s spectrum for Rs25,000 crore, despite the telecommunication department refusing to issue a no-objection certificate. The 133-acre Dhirubhai Ambani Knowledge City in Mumbai is valued at around Rs17,000 crore. There are many prime properties elsewhere, including one in the heart of Delhi.

Other options include calling joint venture partners for buyout and getting Chinese loans. “The debt is easily serviceable,” said a Reliance official who did not wish to be named.

RCom is hoping to pay Ericsson in time. “RCom has requested urgent approval from its lenders to release Rs260 crore received in income tax refunds,” said a spokesperson for the company after the judgment. The remaining amount would also be raised within the court’s deadline of March 19, he said.

“If the banks don’t agree, Anil can always pay up from his personal coffers,” said an industry observer.

Despite his troubles, it would be unwise to write Ambani off. “He is a battle-hardened entrepreneur and the story is still to unfold in his camp,” said Chandramouli. “It would be a fallacy to think that he would not be able to recover from the current state of businesses.”

Ambani’s best bet is cashing in on the businesses that are faring well and building on his investment in sectors with bright prospects. Moves are afoot to sell off Reliance Capital’s 42.88 per cent shares in Reliance Nippon Life Asset Management. There are other recent ventures, too, like the Pipavav Port in Gujarat, and his interests in infrastructure projects like airports. His companies’ shares that tanked last month are now picking up—Reliance Power rose 19 per cent in the first two weeks of March. Also, most lenders have promised to hang on to the shares pledged to them till September 30.

Ambani may still manage to land on all-fours, but there are new challenges. Questions are being raised whether he is fit to go ahead with his latest venture, Reliance Defence, which is one of the offset partners of France’s Dassault Aviation for the delivery of 36 Rafale jets. The issue has already rocked Indian politics and could stay burning as the nation heads to the polls. Said Chandramouli, “His perceived or real proximity with the current government also makes the ensuing election results an important point that can impact his businesses.”

Wrong signals

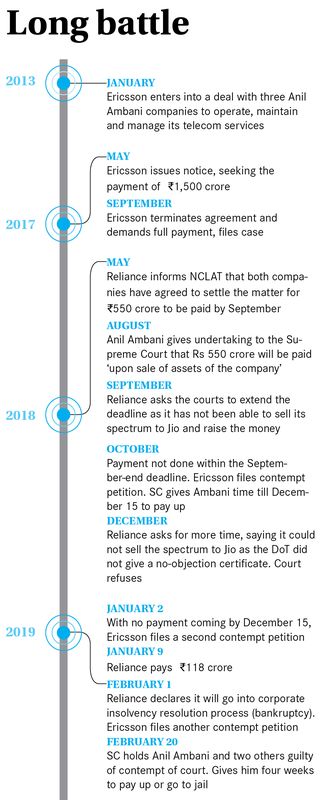

Ericsson, a Swedish business-to-business service provider, serves telecom operators around the world. At the heart of its case against Anil Ambani is the fallout of an agreement with Reliance Communications and two associate companies, Reliance Telecom and Reliance InfraTel, to manage Reliance’s telecom network.

What was considered a bounty for Ericsson when the deal was signed in January 2013 soon turned into a bane once unpaid invoices started piling up over the following four years. Ericsson threatened to terminate the contract. This led to amounts being paid in advance for a few of months, but not the pending dues.

With unpaid invoices piling up, Ericsson issued three notices in May 2017, to which Reliance retorted saying Ericsson’s performance was inconsistent. Soon Ericsson terminated the agreement and asked for the payment in full, about Rs1,500 crore. In May 2018, the National Company Law Tribunal appointed interim resolution professionals under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. Reliance quickly got a stay on the insolvency proceedings from the appellate tribunal promising that it will settle the matter for Rs550 crore, to be paid within September 30.

At this point, Anil Ambani made two crucial mistakes. He approached the Supreme Court, asking for the insolvency proceedings in the NCLT to be quashed as an agreement had been reached, taking the dispute straight into the highest court of the land. Secondly, his affidavit said that the payment would be made ‘upon sale of assets of the company’.

Ericsson cried foul at the new condition. To make matters worse, Reliance approached the courts three days before the deadline to pay up, asking for an extension by 60 days. Ambani’s intention was to offload the vast amount of spectrum he had acquired in 2008 to his brother Mukesh’s Reliance Jio. By then RCom had stopped consumer services, while Jio was raring to go.

As no payment was made on the due date, Ericsson filed a contempt of court petition the next day, on October 1. When the hearings came up, the court gave Reliance time till December 15 to pay, with interest from the original due date. It was also made clear that the contempt petition would be revived if the payment was not made by December 15.

Again, three days before the new deadline, Reliance asked the courts for more time. It told the court that it was ready to sell the spectrum to Jio but the DoT was refusing to give a no-objection certificate to the sale. DoT wanted an undertaking from Jio that it would also be responsible for all existing and future dues from RCom. But Jio refused to give it.

With no payment coming on December 15, Ericsson filed a second contempt petition on January 2, the day the courts re-opened after holidays. Meanwhile Reliance paid up Rs118 crore, saying the remaining Rs453 crore (including interest) would be paid by January 30.

As the rest of the money did not materialise on January 30, RCom did something dramatic. On February 1, it filed for bankruptcy. An alarmed Ericsson (a company lawfully adjudged bankrupt would mean claims of creditors would be put in abeyance) promptly filed a third petition of contempt.

After hearings, Justices R.F. Nariman and Vineet Saran held Ambani and two of his associates guilty. He has until March 19 to pay up the remaining amount or go to jail.