Imagine that you are a villager in India. You live in a close-knit village which follows the feudal system, with the zamindar lording it over from his mansion. There are only a few specific jobs, confined to your mohalla, that you are allowed to do and make money out of; the larger part of the earnings from the fields you toil in go straight to the landlord, who has promised to return your share in due course.

Then, out of the blue, everything goes awry. Not just in the village but the entire region. A locust attack, otherwise uncommon, takes place, destroying all means of livelihood. The zamindar issues a diktat that all work, in the fields and otherwise, should be stopped and the villagers should drop what they are doing and take refuge inside their tenements. This is the only way to save yourself, and the village, he tells his startled fellow citizens, who are now not just facing an unknown enemy swarming all over the fields and dashing hopes of their regular subsistence earnings, but placing a question mark over the expected ‘cashback’ from the landlord.

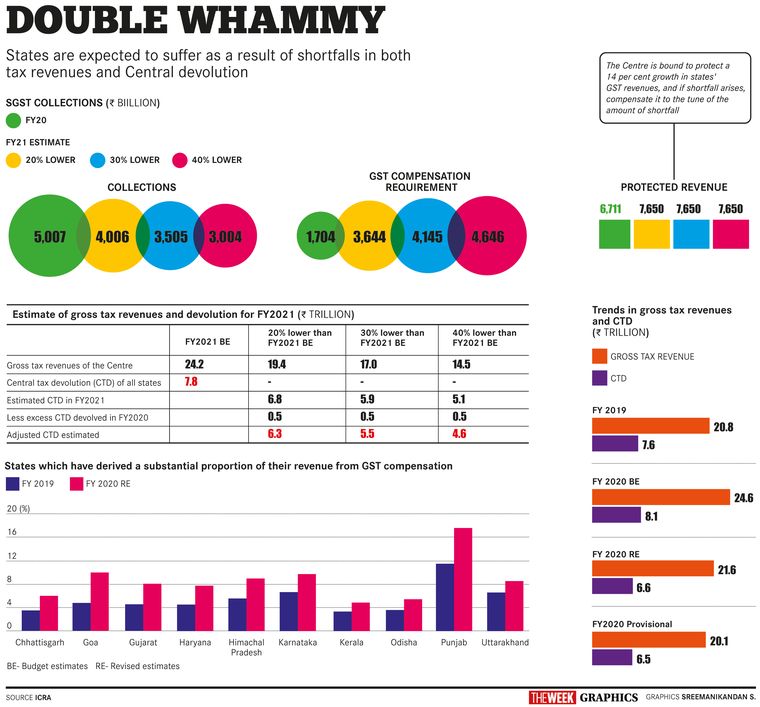

Virtually every state in India right now is you, reeling over a double economic whammy—the Covid-19-induced lockdown has reduced their own meagre revenues to a trickle, and the Centre, on whose handouts the states depend on for a good chunk of their expenditure, has been forced to tighten its purse strings. The result? The economic position of every Indian state is a shambles.

“Punjab’s financial situation is extremely critical,” says Chief Minister Captain Amarinder Singh. Goa Chief Minister Pramod Sawant says the state has had to face “extreme hardship,” while West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee says her state is “financially starved”. Chief minister after chief minister has sent SOS letters to Prime Minister Narendra Modi asking for urgent financial help.

The economics is spilling into political friction. Centre-state relations have not been exemplary since Modi came to power in 2014, but now, the gloves are off. Not just between New Delhi and the states, but between embattled states themselves, boxed in from both sides of having to deal with rising infections as well as dwindling incomes.

AN UNEQUAL RELATIONSHIP

Indian states essentially spend money from two sources. First is the income they make directly from the few things they are allowed to tax, like petrol, diesel and liquor as well as revenue from land transactions. All other goods and services are taxed under GST, the money going to the Centre from where the state’s share is given back later (and sometimes, not soon enough). The other source of money is what is ‘devolved’ from the Centre, like plan allotment and budgetary allocation for Central government schemes like highways.

The issue? Over the years, problems such as changes in the tax structure like GST and their own profligacy have left most states financially weak. Many borrow way beyond their means. While rules like the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act limit how much states can borrow, previous debt and interest piling up has been a common feature. Tamil Nadu, for instance, has a total debt of Rs4.56 lakh crore, while Karnataka will have to pay more than Rs22,000 crore alone in interest this year. According to a report by the Reserve Bank of India, Punjab has the worst debt-to-GDP ratio at nearly 40 per cent, followed by Uttar Pradesh at 38 per cent.

“States are now more dependent on the Union government,” says Avani Kapur, director (accountability initiative) and fellow, Centre for Policy Research. “While part of this is inherent in India’s fiscal structure where states are the big spenders and the Centre controls the purse strings, the situation has been exacerbated by the introduction of the GST… eroding the ability of states to raise their own revenues.” For example, while money raised by states themselves was 55 per cent in average of their total expense in 2014, it has fallen to barely half now.

“The state of state finances is bad, no doubt about it,” says Hemant Sharma, principal secretary (industries), Odisha. “But that is because state finances are directly dependant on economic activity and devolution from the Central government.”

The lockdown hit both. Money coming in from alcohol, petrol and electricity, the main sources of direct revenue for states, virtually plummeted overnight when the national lockdown with its draconian provisions kicked in on March 25. And, for all practical purposes, most Central schemes and grants approved for this year will remain suspended till the end of the financial year, as the Centre itself is strapped for cash. Ratings agency ICRA estimates that tax devolution from Centre to states will be down by 30 per cent this year.

ALL FALL DOWN

Adding to the woe is the fact that not only are states on the frontline of fighting the pandemic, with health care being a state subject, they also have immense expense obligations, ranging from salaries to pensions to social security schemes. To go back to the initial imagery of the villager being an Indian state, imagine how it would be while your salary has been cut. You are now saddled with the unenviable task of not only providing for your family members, but also shelling out for Covid-19 treatment of infected relatives. Not a good ‘state’ to be in, right?

For example, in the month of April which was completely washed out by the lockdown, Kerala’s finance minister Dr T.M. Thomas Isaac could only watch helplessly while the state’s revenues crashed to just over Rs1,000 crore—it was four times that in the corresponding period the previous year. Meanwhile, the state’s expenses went up from nearly Rs9,000 crore to more than Rs15,000 crore. The result? The state’s deficit crossed 40 per cent of its budget in just the first month of the financial year.

The horror story is repeated across the board. Telangana Chief Minister K. Chandrashekar Rao had to make do with 25 per cent income compared with the previous year, while Nitish Kumar in Bihar had to be satisfied with 18 per cent. Amarinder Singh during one of the prime minister’s video chat with chief ministers claimed that Punjab’s income had crashed to 12 per cent. Chhattisgarh’s GST revenue fell from Rs1,200 crore to Rs200 crore in April, while that of Jharkhand went from more than Rs800 crore to a little more than Rs100 crore.

So, the states did what they always do—clamour for help from Modi and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman. Only, this time the Centre itself was trying hard to figure a way out of its own snare to throw any benevolent scraps their way.

CONDITIONS APPLY

The only direct relief came as part of Sitharaman’s ‘Covid stimulus’ series of announcements, with the limit on how much money states can borrow increased from the existing 3 per cent to 5 per cent. But it comes with a catch. Only an additional 0.5 per cent is unconditional. Anything further depends on how fast the state digitises ration cards and sets about reforming their electricity sector. Obviously, it has not gone down well, especially among opposition-ruled states. “This is violative of the country’s federal structure,” says Amarinder Singh.

“Increase in borrowing powers of states is a step in the right direction, however, if it is made conditional, it constrains the fiscal space,” says Lekha Chakraborty, economist and professor at the Delhi-based National Institute of Public Finance and Policy. “The fundamental change has to come in debt deficit dynamics.”

“Most of these consumption drops, like the electricity consumption lost for the 60 days or so of the lockdown, cannot be recouped in the latter part of the year. They are a net loss,” says Hemant Sharma of Odisha. “Of course, as industrial activity restarts, there is going to be a rebound in some sectors. But no state is sure at the moment as to how much of the loss can be made good in the months to come.”

DISUNITY IN DIVERSITY

While the states are on the same boat as far as dwindled revenues go, the misery has been different for different states. By a twist of fate, the more developed states have been the hardest hit. According to a Crisil study, top eight states affected by the pandemic, like Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, accounted for 65 per cent of manufacturing, 60 per cent of construction and 53 per cent of services, meaning the overall impact on the economy was further accentuated by businesses being affected here.

Liquor, too, can make or break fortunes. Uttar Pradesh and Telangana, for example, are most dependant on excise from liquor, affecting these states that much more as revenues dried up during lockdown. Alternatively, Gujarat, a dry state, depends way too much on petrol and diesel tax, and got battered as lockdown dialled it down to a trickle.

BEST FOOT FORWARD

Ditched by the Centre and left to their own devices, states have surprisingly resorted to a level of dexterity and enterprise many of them are not really a natural at—rolling out the red carpet to investment. Besides the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ and the ‘vocal for local’ narrative, states were also catalysed by a specific exhortation to them from Modi to woo businesses leaving China.

Thus, while Gujarat wrote to the Japanese government and business houses, offering them land and subsidies, Uttar Pradesh has set up an economic task force to showcase its business hubs bordering Delhi, and the upcoming defence park and the Jewar airport. “We have been receiving good response from foreign businesses who want to invest,” says Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath in an exclusive interview with THE WEEK.

German footwear brand Von Wellx shifted out of China to set up a footwear unit in Agra on the invitation of the Uttar Pradesh government, which says the project will throw up 10,000 direct and indirect jobs. Says Ashish Jain, director and CEO of Iatric Industries which handles Von Wellx’s Indian operations, “The UP government was very eager to help at different levels and has also announced economic packages for companies moving in. This was a major parameter.”

Invest India, the Union government’s investment promotion agency, recently facilitated a series of meetings for states like Maharashtra and Telangana with global electronics majors like Apple, Intel, Samsung and LG. States like Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka are also interested in following suit. Invest India plans to conduct similar sessions for other sectors, too, starting with pharmaceuticals.

From Assam, which highlights its subsidised electricity for industries as a USP, to Punjab, which points out how its ‘Invest Punjab’ department’s single-window clearance facility assures ease of business, and Odisha which touts its stable and well-administered investment-friendly climate, the go-get-it attitude is palpable. Andhra Pradesh Industries Minister Mekapati Goutham Reddy recently said, “We call ourselves ‘providers’. We were the fastest in opening up after the lockdown.”

Guruprasad Mohapatra, secretary of the Union government’s department for promotion of industry and internal trade (DPIIT), says each state can be a champion in their areas of strength. “As we aim for more global brands (as part of the PM’s call), states will play a major role in this.” Sawant recently wrote to Modi that the economic slowdown would help in exploring other opportunities.

WHAT ABOUT THE HERE-AND-NOW?

Not everyone thinks it is the right approach, though. “To me, it looks quite weird to compete for factories moving out of China at the state level,” says Chakraborty. In her view, the focus should be on increasing public health infrastructure and services and in tackling hunger and loss of livelihood issues. “Decisive public infrastructure investment alone can attract private investment,” she says. “Ease of doing business, judicious labour reforms and climate-related policies are crucial determinants.”

With investments still a work in progress, there is also the question of what the states can do to meet their dire scenario right now. There is, of course, hope-against-hope for some financial assistance yet from the Centre. “Reforms, of course, will help, but will take time. Meanwhile, some additional funds to state governments is definitely desirable,” says Sharma.

GST compensation is something states are banking on—as agreed when the GST Council was set up. The Centre is supposed to make up for any drop, if actual revenues to states do not grow by 14 per cent every year. Sitharaman has convened the next GST Council meeting in July only to discuss whether they can borrow from the markets for GST compensation. Meanwhile, reports that the Centre may try to wriggle out of paying by invoking the force majeure (act of God) clause (though the provision is not there in the GST Act) has further alarmed desperate states.

Other options include debt restructuring, tapping the bond market and, of course, squeezing money out of your own sources. “The shift is already beginning, with the proportion of revenues coming from alcohol and stamp duties increasing,” says Kapur. A tried-and-tested means to increase state income has always been ‘hitting the bottle’. As liquor vends re-opened, for example, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal did not think twice before slapping a 70 per cent Covid cess on liquor. West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh and Haryana promptly followed suit with their own price hikes. Starved of their poison for more than 40 days during the lockdown, relieved tipplers did not particularly seem to mind.

Just as the Centre’s Covid relief package aims at structurally reconfiguring business and industry, states are also hoping that the shake-up throws up fresh opportunities—Adityanath manoeuvring to optimise the return of migrant labourers by putting them to work in industries which he hopes will come up soon is only a case in point. Haryana Deputy Chief Minister Dushyant Chautala summed it up succinctly at a business continuity webinar recently, “If I see it as a crisis, it will be hard. [So why not] see it as an opportunity?”