In 2005, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman told a sob story about why, despite their pretensions, economists are not scientists.

The occasion was the Bhagwati Festschrift in Columbia University—a conference and gala dinner (Festschrift roughly means feast-script in German) in honour of Jagdish Bhagwati, Krugman’s teacher and an authority on trade theory. After suitably identifying himself as a SOB (acronym for ‘student of Bhagwati’), Krugman revealed his strongest memory of studying with the great man. It was an old joke. “At one point, Jagdish explained to us his personal theory of reincarnation,” Krugman said. “It was that if you are a good economist, a virtuous economist, you are reborn as a physicist, and if you are an evil, wicked economist, you are reborn as a sociologist.”

The joke, he said, was not on sociologists or physicists; it was about economists. “They aspire to what they imagine physicists to be, to this rigour and certainty and mathematical complexity,” said Krugman. “Given his record of achievement, progress, open-mindedness, and just sheer human goodness, I am sure that Jagdish will be reborn as a physicist.”

Sadly, economists waiting for rebirth still have the unenviable task of making sense of the world. With their theories and mathematical models, many of them acquit themselves well, but the fact remains that economics perennially plays catch-up in solving poverty, unemployment and inequality.

But economists do get to conduct experiments like physicists do. Communism, for instance, was an experiment born of the ideas of a German economist. (Karl Marx had put his politics before his economics—he published the Communist Manifesto two decades before Das Kapital.) When the socialist experiment failed, free-market economists took over. Jeffrey Sachs of Harvard University tried to rescue the Soviet Union’s largest rump state, Russia, with an economic “shock therapy”—ending price controls, opening up markets, privatising state-owned industries and lowering spending, all done in warp speed.

The therapy did not work. The economy tanked, the ruble hit rock bottom, bread and milk became scarce, and politicians stripped government assets to enrich themselves. Angry and disillusioned, Russians returned to the order that autocracies often provide.

India, too, recently had a shock therapy-like experiment. In November 2016, the government announced demonetisation of Rs500 and Rs1,000 notes. Paper money worth Rs15.41 lakh crore was rendered void. The reason: some economists believed that at least 5 per cent of India’s cash economy was illegal, and so withdrawing the high-value notes would have the effect of a forcible wealth transfer to government coffers. Since those with black money would not risk depositing it in banks, the RBI would be left with a currency surplus—around Rs3 lakh crore—that it could transfer to the exchequer.

These economists calculated that demonetisation would help the government earn money. But then, as some others have been saying, governments do not really need to earn money. They are in the business of issuing money. For instance, the Indian rupee comes from the Indian government, and nowhere else. The RBI prints the money for the government—as coins and notes—and then infuses it into the economy in various ways. In other words, the Indian government is the monopoly manufacturer of Indian rupees. Or, the government is like a household, but with its own money-printing press. What would be the chances of such a household ever going broke?

Mystified about the economics of it all? It could be that the way we think about money is seriously wrong. The last time there was a fundamental change in the way people thought about money was in the 1970s, when US president Richard Nixon delinked the dollar from gold. Until then, it was theoretically possible to exchange a currency note to obtain an amount of gold that was equivalent to the note’s value. The ending of this gold-exchange standard meant that the dollar—and all sovereign currencies pegged to it—had become fiat money.

Rupee, too, is fiat money, which means that the pieces of paper in your wallet do not have intrinsic value. Whatever value it holds boils down to the currency’s backing of the government (in the visible form of the governor’s promise on the note) and the market’s trust in the monetary system (in the invisible form of exchange of goods and services for paper).

All this leads to an important question that even famous economists—from Marx to Krugman—have struggled to answer in concrete terms.

What really is money?

The motorcycle economist

“What exactly is money?” the historian Niall Ferguson asked in the introduction of his book The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World. “Bread, cash, dosh, dough, loot, lucre, moolah, readies, the wherewithal: Call it what you like, money matters. To Christians, the love of it is the root of all evil. To generals, it is the sinews of war; to revolutionaries, the shackles of labour. But what exactly is money?”

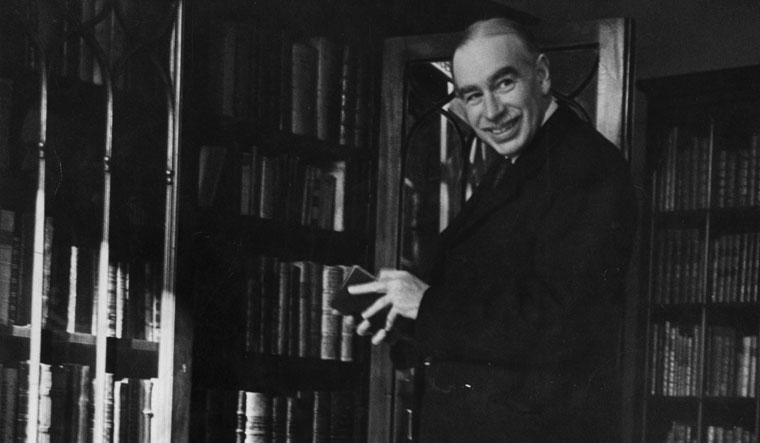

Let us start our search for the meaning of money in August 1914, when a lanky young economist undertook a 100km motorcycle journey from Cambridge to London to save the British Empire.

John Maynard Keynes, 31, was a gifted mathematician who had spent the previous year in the India Office in London, studying the colony’s rather crude monetary system. In his 260-page book Indian Currency and Finance, he argued that India’s currency need not be convertible to gold in matters regarding internal trade. This was a radical view, because gold was considered the safest repository of value—an asset universally recognised.

The value of all sovereign paper currency lay in the promise that one could take it to the central bank and obtain gold in exchange. This gold standard required that the central bank keep a fixed amount of gold for every unit of paper currency issued. The system worked like insurance. As former US president Herbert Hoover said, “We have gold because we cannot trust governments.”

Keynes’s book sold less than 1,000 copies, but its subtle inventiveness impressed key figures in the government. Keynes hitched a ride from Cambridge (where he studied) to London as a government officer “wanted to pick your brains for your country’s benefit”.

In August 1914, London was in panic. Barely two months before, a young Yugoslav nationalist had shot dead the heir to the throne of the sprawling Austro-Hungarian Empire—an act that would trigger World War I, but whose first effect was a pan-European banking crisis. The political uncertainties caused by the assassination had made investors and traders dump paper currencies and take refuge in the security offered by gold.

Since the pound sterling was the dominant currency, Britain’s central bank, the Bank of England, gradually went into a squeeze. Volatile currencies across Europe were being converted to pound, and then presented to the Bank of England in demand of gold. The bank was bleeding bullions, as the crisis forced governments across Europe to withdraw gold from London to shore up their own central banks. The vaunted stiff upper lip quivered and the Brits themselves liquidated their paper-money positions. In just three days, the bank lost two-thirds of its gold reserves.

The government swung into action, shutting down stock markets and declaring an unprecedented, four-day bank holiday to prevent further outflow of gold. When the motorcycle carrying Keynes puttered into London, bankers and mandarins were already toying with the previously unthinkable idea of defaulting on their currency obligations to protect the remaining reserves.

Keynes, an aristocrat who believed in Britain’s right to rule the world, was aghast. “The bankers,” he wrote to his father, “have completely lost their heads and have been simply dazed and unable to think two consecutive thoughts.”

He realised that Britain needed to not just merely survive the crisis, but survive it in such a way that its reputation as a reliable financial power was preserved and its political dominance cemented. So he wrote to David Lloyd George, chancellor of the exchequer and future prime minister, that if Britain ever defaulted on its obligations, “the future position of the City of London as a free gold market will be seriously injured”.

“One consideration never to be forgotten is the following,” Keynes told Lloyd George. “It is useless to accumulate gold reserves in times of peace unless it is intended to utilise them in time of danger. If [talk of defaulting on obligations] is believed in international banking circles, our position and prestige will be very different from what they have been in the immediate past.”

He then presented an audacious proposal. Foreigners who wanted to convert pounds to gold should be paid in full, he said, while domestic obligations be met with a new sovereign paper currency that would be convertible to gold only in the London headquarters of the Bank of England.

This would achieve two primary goals. One, the run on the Bank of England would subside, helping the bank preserve gold for obligations abroad. Two, the suspended economic activity within Britain could resume. Of course, people could still redeem new notes for gold, but the effort would be taxing. The provision that gold could be redeemed only in the London headquarters meant that there would be travel, delays and hassles.

Lloyd George, a man of firm belief that “you can’t cross a chasm in two small jumps”, ran with Keynes’s plan. Bills were hurriedly passed in parliament and the new money was printed and distributed on a war footing. When the commercial banks reopened, people accepted the paper money and began making deposits. Most of them reckoned that they were better off doing business with the new paper money than taking the trouble to exchange it for gold.

Together, Keynes and Lloyd George had provided an economic springboard for the British currency to take a giant leap over a deep financial chasm. They had legally weakened the gold-exchange standard.

The idea of money would be never be the same again.

The race-car economist

Warren Mosler was born in 1949, three years after Keynes died. An American economist, Mosler is the father of modern monetary theory, or MMT, a macroeconomic framework that upends the notion of how money works in a modern economy. As an economic theory, MMT is considered post-Keynesian—deriving its ideas from, and expanding on, Keynes’s work.

Mosler is a renaissance man like Keynes was. Keynes was a connoisseur of arts, culture and philosophy, and counted among his friends personalities as varied as the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and the English writer Virginia Woolf. Mosler, 71, is as knowledgeable about politics, business and race-car manufacturing as he is with complex economic concepts. He made his wealth in the 1980s running a hedge fund, founded an automotive company in 1985 that changed the definition of the modern race car, transitioned back to academia and policymaking in the 1990s, and later ran for US president and the US senate.

Intellectually, his most famous children are MMT and a groundbreaking race-car called the Consulier GTP. The GTP had an eggshell-like lightweight chassis and a carbon-Kevlar body that made it 50 per cent lighter than the average American sports car. The car’s feathery body, aerodynamic design, and the 2.2-litre turbocharged four-cylinder engine made it a peerless beast. Its build philosophy: The lighter the machine, the more efficient and agile it is.

MMT reflects the same attitude. It is a heterodox economic theory that has a simple, powerful idea at its core. The idea: Currency is a public monopoly that can serve to attain full employment.

Agreed, the idea makes for an ugly sentence. The Consulier GTP, too, was an ugly machine, which is why it did not have many takers. (Mosler sold just 83 cars in 11 years.) Likewise, though MMT has a cult-like status among economists and activists, not many policymakers have embraced its innovative views.

One reason is that MMT gives no direct prescriptions to cure economic ills. “MMT is descriptive,” Mosler told THE WEEK. “It describes the workings of the monetary system of each nation, which tends to reveal policy options not previously considered viable.”

Currently, the monetary systems of most nations are interlinked. That is because of the work of Keynes and a US treasury official called Harry Dexter White. In the 1940s, they laid the foundations of two institutions that would shape the post-war global economic order—the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The IMF would facilitate international trade and enhance global monetary security and cooperation, while the World Bank would provide the required money to help developing countries grow.

The IMF took up office on the 19th Street in Washington, DC—not far from the US Treasury on the 15th Street. In the 1980s, when Mosler was beginning to make a name as a hedge-funder manager, the proximity between the US government, the IMF and the World Bank led to the formation of a ‘Washington Consensus’, on what constituted good developmental policies.

As a UN diplomat in New York, Shashi Tharoor had a ringside view of how that consensus was sold to the developing world. In his new book, The Battle of Belonging, he writes: “Neoliberalism came into its own, privileging a heady cocktail of free-market policies, including deregulating capital markets, lowering trade barriers, eliminating price controls, establishing global supply chains, rampant privatisation, and the reduction or abandonment of state welfare for the poor, often accompanied by austerity measures to bring fiscal policies in line with what western ratings agencies wanted to see.”

The policies, however, were designed to benefit the developed world. “It was not a consensus forged in the developing countries—among those that were living through the consequences of those policies,” wrote the Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz. “It was only a consensus among those who imposed the policies, not among those who experienced the bulk of their efforts, especially the negative ones.”

Some policies, though, did benefit India. “For over forty years after independence, India operated under a plethora of economic controls—an understandable response to centuries of colonial plunder,” Tharoor told THE WEEK. “After the controls were dismantled during liberalisation in the early 1990s, growth surged from the dismal ‘Hindu rate of growth’ to triple that level, pulling millions out of poverty. The record shows that more open trade has provided immense, concrete benefits to ordinary Indians.”

But at the heart of the Washington Consensus is a thinking that MMT economists regard as a giant folly. The ‘folly’ is in thinking that the fiscal deficit—the difference between government revenue and expenditure—needs to be reined in; that the government, like any ordinary household, cannot live beyond its means.

MMT makes a clear distinction between the government and citizens: The government is the issuer of money; the citizens are the users of it.

One of Mosler’s life stories is particularly illustrative of this difference. He had a beach-front property with all the amenities. One day, he asked his two children to help him keep the house clean and habitable. Mosler told them that, in return, he would give them his business cards, which they could make use of in profitable ways.

The system would work like this: Three business cards for making their beds; five for doing the dishes; and ten for washing the car or cleaning the swimming pool. A few weeks later, Mosler realised that the system was not working; the children were not doing any work. When he asked them why, they replied, “Dad, why would we work for your business cards? They are not worth anything!”

Mosler changed his strategy. He realised that he had to make the children need the cards. He issued a dictum: At the end of each month, he wanted each child to pay him back thirty of his business cards. Failure to pay would result in loss of television time, trips to the mall, use of the pool, and suchlike.

That did the trick. Mosler had effectively imposed a ‘tax’ on his children, one that could only be paid using his ‘sovereign’ paper currency—his business card. Every month, the children will have to do the required work to earn the ‘money’ and pay the ‘tax’; also, they will have to go through the earning-paying cycle every month.

MMT’s core philosophy is this: Taxes are primarily meant to create demand for government currency.

Tax revenues, according to the theory, are beside the point. A government needs people to pay taxes as much as Mosler needed his children to pay back his business cards.

“The monetary system functions first to provision the government with goods and services,” Mosler told THE WEEK. “Tax liabilities are imposed to make the population become sellers of goods and services, to obtain the funds needed to pay taxes, [the currency for which can] come only from the government.”

This is a profoundly innovative view. But the question is, how relevant is it for India?

The Indian money crises

India, like most developing countries, has been facing a revenue-expenditure crunch. The government does not have the money that needs to be spent on education, health care, infrastructure and social welfare. The overall annual spending is hugely skewed: Last year, the Union government incurred Rs23.49 lakh crore as ‘revenue expenditure’—salaries, pensions, subsidies, interest on debt, and so on. Only Rs10.59 lakh crore was ‘capital expenditure’—creation of assets (like roads, bridges and schools) and measures that eased the debt burden.

This skewed spending ratio—coupled with the Washington Consensus-induced preoccupation with controlling the fiscal deficit—makes it difficult for the government to find money for productive social welfare schemes. For instance, the government currently spends around Rs60,000 crore a year on the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, which provides minimum-wage jobs to unemployed people in villages. The NREGA is a hugely successful scheme that benefits six crore families a year, but the government’s fiscal constraints prevent it from expanding the scheme.

This is where MMT is relevant. Even though Mosler insists that the theory is “descriptive”—of how monetary systems work—policymakers could well divine real-world solutions from it. For instance, governments can print money to meet its expenses. And spend that money on schemes that would provide full employment and other productive outcomes. It means, in Mosler’s words, toying with options previously considered unviable.

MMT, however, also envisions checks and balances to prevent a free-for-all situation. In The Deficit Myth, one of the foundational texts in the field, economist Stephanie Kelton lays out some real-world conditions. “Countries need to do more than just grant themselves the exclusive right to issue currency,” she writes. “It’s also important that they don’t promise to convert their currency into something they could run out (gold or some other country’s currency). And they need to refrain from borrowing in a currency that isn’t their own.”

This is a big ask, though. In the globalised economy, currencies are interlinked, and so are their values. It is not possible for the Indian government to issue rupees that are not legally convertible to dollar or other currencies. It means the rupee runs the risk of being devalued if not properly ‘managed’.

But governments can certainly meet one condition: Refrain from borrowing in a currency that is not their own. Even non-sovereign governments have the option of doing it. A good example is how the Kerala government became the first Indian state to tap the market for masala bonds, which are debt papers sold overseas that are denominated in rupees. In other words, borrowing from overseas money market in Indian rupee. In May last year, the Kerala government, through a state-owned corporate entity, successfully issued rupee-denominated bonds worth around 02,000 crore in the London Stock Exchange. The long-term debt will be paid back in rupees, and not in dollar, irrespective of the prevailing exchange rate. (Ironically, it was a communist chief minister, Pinarayi Vijayan, who rang the exchange’s iconic bell to begin trade. Marx would have been proud; he, too, had dabbled in money trading in capitalism’s most storied stock exchange.)

According to Tharoor, economic crises are an excellent time for unorthodox economic thinking. But then, there are the pitfalls to consider. “In my view, India walks a delicate tightrope,” he said. “Overtly tight fiscal-deficit controls should not be allowed to straitjacket growth; after all, such a policy would only lead to further economic sluggishness. At the same time, here is the dilemma: employment requires investment, and investors would surely be loath to invest in India if our fiscal deficit is worryingly out of control.”

In the early 1990s, New Delhi was caught in such a situation, one that was not very different from the one London found itself in 1914. Political turmoil and economic headwinds had landed India in a position where it could not afford to pay obligations abroad. The panicked government sounded economists out on all kinds of drastic measures.

One measure that was secretly discussed was a ‘demonetisation’ targeting non-resident Indians. “At one stage, my opinion was asked about freezing outstanding NRI deposits with banks in India,” wrote Y.V. Reddy, who then headed the balance-of-payments division at the RBI. “This meant that NRIs would not be able to temporarily cash their foreign currency deposits. I suggested that such an option should not even be brought up in any discussion or any background document. Once the nation lost the confidence of the Indian diaspora spread over various countries, its self-respect and pride would stand seriously undermined.”

In the end, the government decided to pledge its gold in London to mitigate the crisis. Later, finance minister Manmohan Singh would start the much-needed process of liberalising the economy. Reddy, who had issued a Keynes-like warning to the government, would become RBI governor. The crisis-related chapter in Reddy’s post-retirement memoir, however, has a very un-Keynesian title: The power of gold.

“We still suffer from the gold-exchange hangover,” said R. Rajender, economist and founder CEO of SR Capital Advisory, a Chennai-based corporate investment consultancy. According to him, the balance-of-payment crisis happened because the rupee had a fixed exchange rate.

A fixed rate is the regime by which a government ties the exchange rate of its sovereign currency to another country’s currency, or to the price of gold. The objective is to protect the currency from extreme volatility. In the 1990s, the rupee’s fixed exchange rate was tied to the US dollar.

“What happened [in India] is exactly what tends to happen with fixed exchange rate regimes,” Mosler told THE WEEK. “Understanding the difference between fixed and floating exchange rate policies is what led the IMF cease recommending fixed exchange rate policies, and instead encourage floating exchange rate policies, [so that] what happened to India need never happen again.”

So, are the lessons from the 1990s still relevant? “First, we need to understand that most of the currencies are fiat currencies now, except European Union countries and a few others. It is not linked to gold or dollar any more,” said Rajender. “The government being the currency issuer, there is no limit on [issuing money] to back up productive work. As long as employable resources are there, the government can spend. Restrictions like fiscal deficit and debt-to-GDP ratio are self-created, with no sanctity or justification in a fiat currency system.”

To be sure, the ongoing economic crisis is worse than what India had dealt with in the 1990s. In July, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said the pandemic had caused “the worst health and economic crisis in the last 100 years in peace time.”

“Some 40 crore Indians are being pushed below the poverty line,” said Tharoor. “This is a time of widespread economic harm, and a strong and generous programme of direct cash assistance will provide desperately needed immediate relief to the multitude of Indians who are suffering on a daily basis.”

MMT economists, however, do not recommend long-term cash transfers or income-guarantee schemes. “Such measures, without ensuring productive work, would lead to inflation,” said Rajender. And inflation leads to currency devaluation. “With [income-guarantee schemes], the government imposes tax liabilities and then gives people the funds to pay the tax,” said Mosler.

Such handouts can have adverse effects. For instance, Brazil spent billions of dollars on monthly stipends to the unemployed during the Covid lockdown. While it reduced economic inequality, the handouts also led to a spike in inflation and food prices.

A middle path could be what the economist Jean Drèze has proposed: An urban counterpart of the NREGA, in which the government does not guarantee employment, but instead issues ‘job stamps’ and distributes them to approved public institutions—schools, colleges, jails, municipalities, government departments, health centres and neighbourhood associations. The institutions would be free to convert each job stamp to employ people in a specified period. Drèze calls it DUET, or decentralised urban employment and training.

“I don’t have any view on MMT,” Drèze told THE WEEK. “Since DUET is not an employment guarantee but an employment scheme, the level of expenditure is flexible. My sense is that, initially at least, the use of job stamps by public institutions may not be very intensive. Therefore, job stamps could be distributed quite liberally to public institutions, and the cost will not be very large.”

Mosler said the programme could work. “It pays people to work and become more employable for other employers,” he said. “And if the wage is stable, it is not inflationary.”

Too radical a plan? Perhaps not.

At the Festschrift in Columbia, Krugman had revealed the most important lessons Bhagwati had taught him—“open-mindedness, a willingness to see things differently, and not to be bound by an orthodoxy”. “I think one of the things you discover as the years go by is that what seems to be a completely radical break actually starts to fit into the grand tradition—and you see where it actually relates to what came before,” he said. “Then [the break] no longer seems as revolutionary as it did, but that’s fine.”

Such a break, from monetary tradition, happened in 1914. And it could happen again. Surely, India could well use one break.