Along with pulsating last-ball finishes, pandemic scares and Pat Cummins’s generosity, a much-talked-about viral moment of this year’s IPL was something that actually happened off-field and on the screen. The reincarnation of the unflappable Rahul Dravid as a short-fused, tantrum-throwing road rager. Screaming at fellow drivers and smashing outside rearview mirrors with a cricket bat, the cricket legend, who had a reputation for his cool, mild-mannered ways, is seen off-character in an ad that was repeatedly aired in between matches.

The advertiser, CRED, is a tech startup that offers credit card users rewards and cashback for paying on time. If the campaign, conceptualised by comedians of the erstwhile cult favourite AIB, became a talking point for upending celebrity images (another ad shows macho actor Jackie Shroff as a Zumba instructor and singer Kumar Sanu as an insurance salesman), it is no accident. CRED has made quite a splash that has disrupted traditional business models and signalled a new, seemingly limitless, horizon for Indian startups.

“Fifty-nine lakh individuals are part of the CRED community. Today, CRED processes 22 per cent of credit card bill payments in India, including over 35 per cent of premium cardholders,” said Kunal Shah, founder of CRED.

The success has seen investors come calling with loose purse strings. Last month, the Bengaluru-based startup raised $215 million in its latest round of funding, hitting a valuation of $2.2 billion. That made CRED a unicorn, an exhilarating term that refers to startups that are valued at more than $1 billion (roughly Rs7,500 crore).

If you thought that is an incredible achievement for a company that is barely three years old, hold your horses. CRED is just one among a dozen Indian startups that were adjudged unicorns born this year. And six of these were dubbed so in the course of just one week last month, coming as a shot in the arm to a country ravaged by a ruthless second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. These include Meesho, which helps individuals and small businesses sell their products through social media; Urban Company (earlier known as UrbanClap), which offers home services; Mohalla Tech, the parent company of Indian language social media platform ShareChat and TikTok wannabe Moj; and PharmEasy, which sells medicines online.

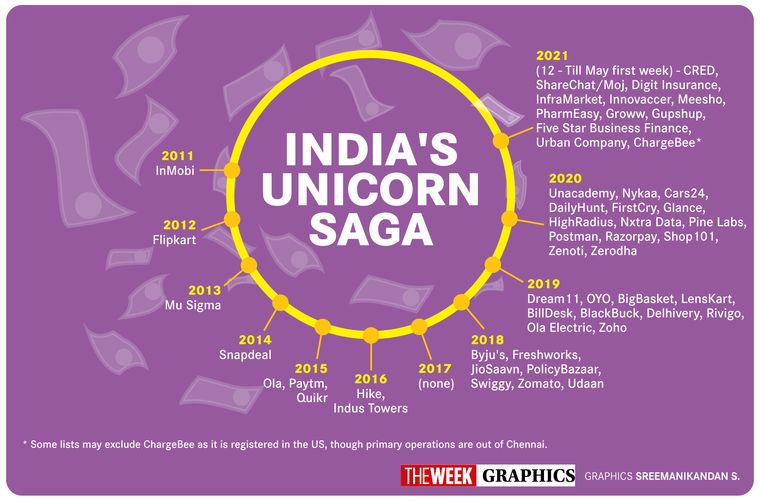

Compare this to the 14 unicorns born last year and 10 in 2019. As 2021 is yet to cross the halfway mark, the prospects of further addition to the Unicorn club are highly likely. A NASSCOM estimate says there are some 216 Indian ‘soonicorns’(soon-to-be-unicorns) bubbling beneath the surface.

“All indicators point to a 50 per cent growth in the number of unicorns that will arrive upon the scene in 2021 as compared with 2020,”said Gaurav Bhagat, business analyst and founder of the Gaurav Bhagat Academy. “As more and more companies around the world look for the money spinners of the future, their journey will bring them to Indian shores. If earlier the motto of the Indian entrepreneur was ‘small isn’t sexy, but it’s sustainable’, the new mantra is going to be ‘go big or go home’.”

While unleashing the entrepreneurial spirit of Indian startups, the increasing confidence of consumers to do business on the internet and easier access to capital had a role to play, and so did the pandemic. The rising unicorn count is not in spite of the pandemic, but partly because of it.

“Opportunities come during adversities,” said Apoorva Ranjan Sharma, co-founder of Venture Catalysts and managing director of 9Unicorns Accelerator Fund. “The pandemic has turned out to be a golden period for the Indian startup ecosystem. The willingness of consumers to pay for digital services has increased phenomenally, thus leading to good customer acquisition for them.”

Lalit Keshre, co-founder and CEO of Groww, an online investment platform, said that the pandemic had accelerated digital transformation in India. “The economic uncertainty due to Covid nudged millions of Indians to re-look at how they managed their money,” he said. He should know, having been a product manager at Flipkart. “The process of investing in financial products in India was too opaque and complex. We brought an e-commerce-like simplicity and choice to the investing experience of Indians,” he said. Groww was started as a do-it-yourself investment platform, helping its millennial users invest in mutual funds without the hassle of brokers, and then it expanded into stocks, ETFs and digital gold.

Groww’s latest funding round saw it joining the unicorn club. The company says it has 1.5 crore users. But Keshre feels it is just the beginning. “Only 3 to 4 per cent of our population is investing in equities. We want to expand this market by un-complicating finance for India’s millennials,” he said.

The potential lights up in green dollar signs for western investors, witnessing the digital shift among Indians post the lockdown, the agile and rapid scaling up by Indian entrepreneurs and the opening up of new investment prospects after the Indian government shut out Chinese investors following the Ladakh clashes. After all, in volume terms, India is the biggest open internet market in the world, and it is still under-penetrated. Everybody wants a piece of the action.

“The extremely low interest rate in the US has also raised the risk appetite,” said Bhagat about the flurry in funding in the past few weeks. Other factors, like the emergence of micro venture capitalists, retail and institutional investor interest in the primary market, hedge funds and a loose monetary policy for at least a few years (keeping interests low to spur business recovery after the pandemic) could mean increased investments, with more companies hitting one-billion-dollar valuations.

Global investor biggies like Tiger Global and SoftBank have been lavish in throwing dollops of dollars at Indian startups. “We believe the market opportunity is huge,” said Scott Shleifer, partner at Tiger Global. The US-based investment firm, if speculations are to be believed, has plans to invest $3 billion in Indian startups. Another report says the company plans to conclude funding rounds with 25 Indian companies this year alone—only 10 have been announced so far.

This obsession with Indian startups does say something about the country’s resilience and resourcefulness. “The new-age entrepreneurs are super innovative and disruptive; they are coming up with crazy ideas every day,” says Sharma. “VCs have stopped chasing me-too startups. They are looking at the pedigree of the founder(s) and what problem the product/service is solving. Just look at some startups that have created a whole new category.”

All this action has not escaped the eyes of India’s big business houses. “Digital adaptation is now in people’s blood. Large successful traditional brick-and-mortar companies saw this coming and made a very effective pivot,” said Bhagat. Sharma, however, feels they are “late to the party”. “The new-age businesses are passionate about solving a problem, to disrupt and are more agile than the traditional behemoths,”he said. The solution would be to “acquire some of these innovative startups going forward.” That, in fact, is already happening, with Reliance Jio’s takeover of e-pharmacy NetMeds and Tata’s acquisition of grocery etailer BigBasket.

While naysayers smell a bubble in this big billion rush, most experts have a different take. “It is a high risk, high reward game!” said Bhagat. “The detractors will be proved right in seven out of 10 cases, maybe even more. There will be more misses than hits, but the hits will cover all the losses and more!” The track record of Indian unicorns is a testimony to this. The country’s first unicorn InMobi (2011) and the early-year unicorn Snapdeal (2014), for instance, have had chequered trajectories since they were adjudged unicorns.

But there are also examples that have soared to the stratosphere. While Paytm and OYO are already decacorns ($10 billion valuation), the latest round of funding of Byju’s puts its value at $16.5 billion, making it India’s most valuable startup.

“At a time when traditional businesses were thrown out of gear by the pandemic, tech-based startups not only stayed afloat, but also went on to create massive businesses,” said Sharma. He is confident of more fat cheques flying in. And if one’s appetite for going big and gaining big is still not satiated, food aggregator Zomato could show the way. It has filed for a $1.1 billion IPO. How the stock is received could be a true testament to whether the unicorn success sagas are worth the hype.