Long before Yana Gupta injected some blood-red oomph into flight safety demos at Kingfisher, and before Indigo stewardesses in their Pan Am vintage look taught India a lesson or two in ‘6E’ efficiency, the original mascot of Indian aviation was a portly, whiskered gentleman in a turban.

Created by Umesh Rao, an artist at the ad agency JWT, in consultation with Air India’s then commercial director Bobby Kooka, the Maharaja made multiple generations not just in India but around the world dream of the glamorous travel aboard the ‘palace in the sky’. It made Air India an epitome of Indian hospitality and world-class excellence.

The exuberance amid India’s chattering classes over the government confirming the sell-off of the beleaguered national carrier to Tata Sons stems a lot from this nostalgia. And the weight of expectations.

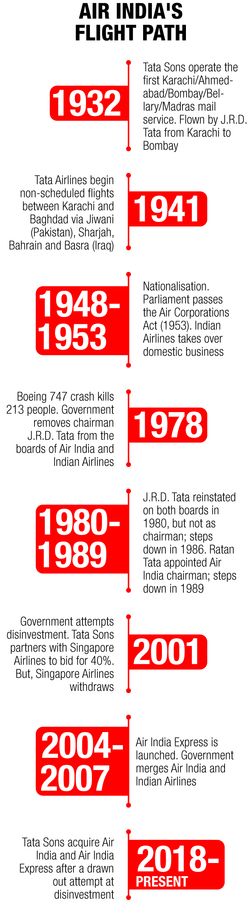

The salt-to-software conglomerate, after all, was the original owner of Air India. Even after it was nationalised after independence, J.R.D. Tata continued to run the airline through the glorious years of aviation in the 1950s and 60s, maintaining its high standards, and then some. Until, of course, a change of government at the centre saw prime minister Morarji Desai unceremoniously dumping Tata. The babus took over and the Maharaja’s downward spiral kickstarted.

The nosedive reached its nadir with Air India’s disastrous merger with Indian Airlines in 2007. The company has not made profits since then, as a classic Delhi (where Indian Airlines was based) versus Mumbai (where Air India was based) turf war to wrest control of the new entity played out. For the record, the capital prevailed, even as the airline’s loss of capital ballooned.

A crash-landing was averted with occasional refuelling—bailouts running into thousands of crores of taxpayer money many times over the past 13 years. And, after a series of near-misses and ‘zero visibility’ cancellations, the government finally managed to deplane the white elephant. Hopes are obviously up that the long-cherished symbol of ‘India’s best’ could again regain its place up among the best in the skies.

“Air India can grow and become one of the finest airlines in the world. But that can happen only in private hands,” Ashwani Lohani had told THE WEEK when he was chairman and managing director of the airline in 2019.

“It is a very, very good buy,” said Sidharath Kapur, former CEO of Adani Airports & former executive director of GMR, which runs two of India’s biggest airports at Delhi and Hyderabad. “It is good for the government, it is good for the Tatas and it is good for India’s aviation sector. Having a strong domestic and international airline like AI under Tatas will support developing International hubs in India, which was a lost opportunity for India.”

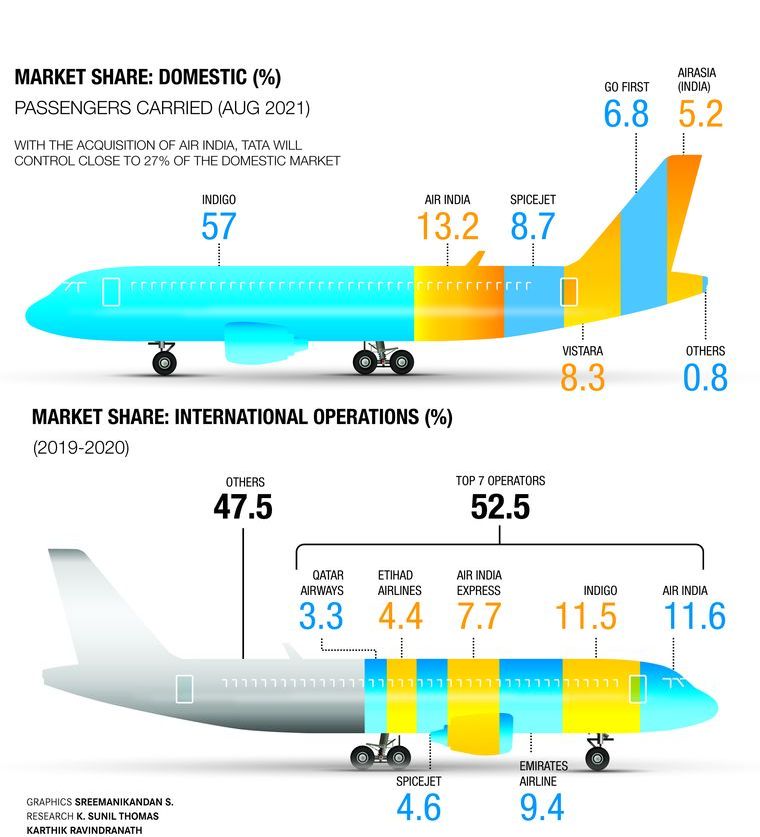

“The consolidated Air India and Air India Express will catapult Tata into a league of mega carriers, with over 200 aircraft, flying to every part of the world,” said Jitender Bhargava, former executive director of Air India. “What would have taken Vistara 10 years and a lot of expenses, they are getting it on a platter.”

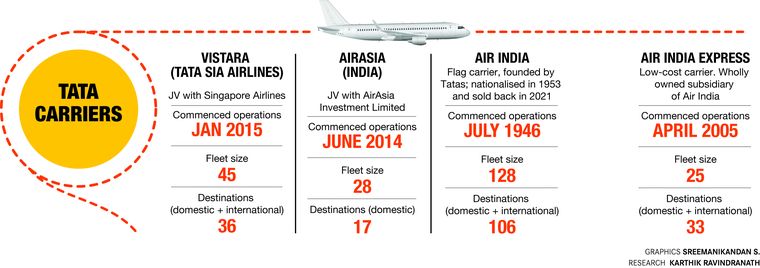

But the road to a possibly glorious tomorrow is paved with uncertainty and challenges. The first being the question of how to deal with four very different airlines in the kitty “(The Tatas) will in due course of time amalgamate the airlines, because otherwise it can’t become an economical operation,” said Bhargava. But it will test Tata’s mettle, with very little in common between the four. Air India and Vistara are full-service carriers, but have different aircraft types and organisational structures. Air Asia India is a domestic low-cost carrier, while Air India Express is an international low-cost carrier, with one using Boeing 737s and the other Airbus A320s.

“History clearly suggests that mergers have not worked well in Indian aviation, be it Jet Airways and Air Sahara, Kingfisher and Air Deccan or Air India’s own merger with Indian Airlines,” warned business guru and motivational speaker Vivek Bindra. Vinamra Longani, head of operations at Sarin & Co, a law firm specialising in aircraft leasing and finance, said the four airlines had vastly different cultures. “They are unique in their own way and have their own set of problems,” he said.

Then there is the trickier challenge of dealing with the 14,034 employees. As per the terms of bidding, no employee can be fired in the first year and a voluntary retirement scheme has to be offered after that. With around 5,000 permanent employees retiring over the next five years and 4,000 staff on contract, Tata will have to deal with it nimbly. Unlike those in the other carriers, Air India unions are vocal and a lot will depend on how they conduct themselves. While the medical benefits issue seems to have been settled by the government, pilots remain an unhappy lot, with a list of demands ranging from arrears with interest to promotions.

“While AI has good trained manpower, work needs to be done over HR policies and culture,” said Kapur. “Other areas to address will be dealing with the high manpower, upgrading the ageing fleet and improving maintenance. Given the Tatas will have multiple airlines, work needs to be done on integrating operations, connectivity, network planning, manpower planning, route development and fleet optimisation. They will have to do a deep dive and over a period of 3-5 years restructure their entire operations.”

Bhargava pointed at multiple areas of “wasteful expenditure”. The crew complement on Air India’s long haul flights, for instance, is way higher than other airlines. “The ability to optimise costs and streamline operations will be a formidable challenge and the key to profitability,” said Suman Chowdhury, chief analytical officer at Acuite Ratings.

While India’s aviation market is yet to come to its senses after the pummelling by the pandemic—all airlines are bleeding—the Air India sale does come as a silver lining. “The prospects are looking good,” said Bindra. “India is already bilaterally engaging with countries to establish a mechanism for mutual recognition of vaccine certificates. So, these steps, along with factors like revenge travelling and businesses opening, would surely bring ‘achche din’ again for Indian aviation.”

It is this sense of optimism that has also seen two airlines waiting in the wings. One is the new avatar of Jet Airways being readied for take-off in early 2022 by its new owners—the Dubai-based Murari Lal Jalan and London-based investor Kalrock Capital—who snapped it up from bankruptcy courts.

“Jet 2.0 aims at restarting domestic operations by Q1 of 2022 and short haul international operations by Q3-Q4 of 2022,” said Jalan, who would become the non-executive chairman of the new entity. “Our plan is to have 50 plus aircraft in three years and over 100 aircraft in five years.”

The other one is Akasa (means ‘sky’ in Sanskrit), an ultra-low-cost airline floated by ‘Big Bull’ Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, which is expected to take flight by summer. The airline got a no-objection certificate from the government a week ago and is planning to place an order for about 50 Boeing 737 Max aircraft soon. “We believe that having a robust air transportation system is crucial for our nation’s progress,” said Vinay Dube, CEO of Akasa.

That is no mean feat considering the dire market scenario. Every airline in the country, nay world, has been losing money since the pandemic broke out. Air India’s annual losses rose from Rs8,556 crore before Covid to about Rs10,000 crore this year. And, oil prices have been zooming up. Aviation turbine fuel prices have gone up 9 per cent in the last month, and 80 per cent in a year. Fuel cost comes to as much as 40 per cent of the cost of running an airline these days.

“High oil prices and pandemic issues will get addressed over a period of time,” said Kapur. India had 14 crore domestic air travellers a year before Covid hit, and expectations are that it will be surpassed once normalcy is restored. “Even if you look at an average middle class Indian travelling once a year, the potential is three times what it is currently. India is an underpenetrated market for air travel,” he said.

While that makes the field attractive for entrepreneurs, for the regular Indian wannabe flyer, the rush of many airliners means the effective index cost of travel has plateaued or actually come down in the last decade. While that helps, sometimes it is more than just economics. As Bindra put it, “Air India is India’s pride, it has an emotional connect with Indians. Its relaunch will benefit passengers and Indian aviation in terms of low fares and more options to fly.”

—With Pradip Sagar