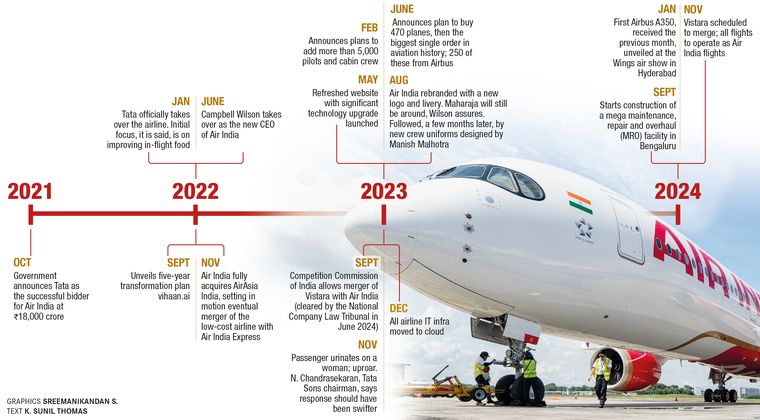

Vistara started doing its wing waves a few days ago. The airline stopped taking bookings on September 3, and will be merged with Air India in two months.

A joint venture of Tata Sons and Singapore Airlines (SIA), Vistara was the only Indian airline to make it to the Top 20 list of World’s Best Airlines this year. But there was little reason for it to continue as a separate entity after Tata bought back Air India from the government in October 2021. It did not make sense for one company to run two full-service airlines, especially with the regulatory approval for SIA taking 26 per cent stake in Air India coming through some time ago.

But the reality in the sky is that there is a world of difference in the service quality offered by Air India and Vistara. “It is baffling that the civil aviation ministry allowed the merger of a modern, well-functioning airline like Vistara with an outdated one and has approved Tata’s decision to rebrand it as Air India,” commented Kapil Chopra, founder of EazyDiner and The Postcard group of hotels and former president of The Oberoi group of hotels.

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE….

When Air India returned to the Tata fold, the expectation was that it would reclaim the lost glory as one of the finest in the world. Instead, it took a turn for the worse. “If people were expecting miracles within a year, that is an impossible task. But now almost three years are over, it is time to show and demonstrate that there have been significant improvements in the operation of the airline,” said Sidharath Kapur, former executive director of GMR Airports and former CEO of Adani Airports. “The honeymoon period is over. People are now expecting more.”

THE PROBLEM WITH THE MIDAS TOUCH

“There is a belief that because Air India once belonged to the Tatas, they have the requisite experience (to run an airline). There can’t be a bigger fallacy than this!” said Jitender Bhargava, former executive director of Air India. “J.R.D. Tata personally, and not Bombay House (Tata Sons headquarters), managed Air India. So for anyone to believe that Tatas have the capability and they will make it into a world-class airline because of past experience is wrong.”

While Tata did get into aviation in the 2010s with AirAsia India and Vistara, both were more investment than operations. But once it acquired Air India, that changed. “Be it Titan (watches and jewellery), Taj hotels, TCS (software) or consumer businesses, there is a certain expectation when people see the Tata name. The airline business, unfortunately, has not lived up to that promise,” said Prof Anand Narasimha, brand expert and professor of marketing at JAGSoM and visiting faculty at IIM Bangalore. “In the airline business, you are not flying planes, you are flying people.”

Even for a salt-to-software conglomerate, the decision to buy a white elephant paying Rs18,000 crore (and a few thousands of crores after that on new orders) was “more an emotional decision than a strategic or rational one”, said Narasimha.

Compounding matters, the five-year transformation process called vihaan.ai saw a series of missteps. “They brought in people from other Tata group companies,” pointed out Kapur. “But then they realised that you cannot bring in, say, an executive from a vehicle manufacturer to run an airline. It takes years of experience to understand the operations of a complex international airline and be adept at it.”

To rectify this, many expat managers were brought in from SIA, including CEO Campbell Wilson, who was heading SIA’s budget airline Scoot.

MAN, NOT MACHINE

Some Air India employees took the voluntary retirement scheme Tata offered after the takeover. And many of those who chose to stay soon started feeling demoralised with “Tata’s own people lording over them”. The once glamorous job with pampering perks had suddenly become a difficult workplace.

“I took this job several years ago despite lucrative offers from other PSUs because a job at Air India was more sought-after, with lots of privileges and perks,” said a senior employee who didn’t want to be named. “But now many of those have been cut down ruthlessly by the new management, from passage facility (free tickets) to lifelong medical coverage. The government had assured us that all privileges will remain, but that word wasn’t kept.”

Adding insult to injury was the notion that Tata was inheriting an incompetent bunch of employees who had lost their edge. “The employees were not bad; they were just demoralised. Their enthusiasm had been killed and they were not led properly,” said Bhargava, “Tata just needed to re-engineer their work practices, but they did not take that course.”

Thus was set in motion perhaps the biggest mistake in Tata’s makeover of Air India―disregarding the employees and the importance of human resources. “Ask any management expert what the key to a merger is? Manpower. How do you integrate the manpower and bring about harmony in work conditions? Same thing again―HR!” said Bhargava. “When they knew the merger was going to take place, they should have taken a merger expert for the role, and not an HR director who was retiring in a few months!”

The result was a trial-and-error style of management which has caused angst across the board. It spilled over this summer with Vistara pilots and Air India Express cabin crew going on strike. “Employees have to understand they are no longer in a government-run airline and need to be productive, efficient and smart,” said Shivram Choudhry of JK Lakshmipat University’s Institute of Management. “Likewise, the management has to understand that this government background attitude will change, but over a period of time. But you can’t come with the attitude that everyone in Air India from the past was no good and anyone from Tata knows better!”

Choudhry said Tata was making the same mistake the government made when it merged Air India and Indian Airlines. “Instead of equipping them to survive and prosper amidst fierce global and domestic competition, that merged entity ended up reporting persistent losses year after year, leading to an accumulated loss of Rs16,000 crore,” he said.

STRENGTHS, WEAKNESSES, OPPORTUNITIES AND THREATS

In defence of Tata and its strategy is a core ingredient―and challenge―of the business: competition.

The emotional legacy and Tata’s track record of buying sick companies and turning them around apart, the only way the Air India acquisition would have made sense was eventually the airline transforming into a cash spewer―akin to Emirates or Singapore Airlines. The opportunity is very much there. India is the fastest growing civil aviation market in the world and even the 1,000-plus aircraft ordered by its airline companies may still turn out to be inadequate if the growth continues with the same momentum.

In this scenario, not using its prized airport slots all over the world or not flying on all the routes was not an option, even if your planes and crew were not the best. “If Air India had withdrawn those services, other airlines would have taken that market,” said Bhargava. “To regain that market share in the next five years after the new aircraft arrived would have taken considerable amount of time and money. Tata’s decision to continue despite using older planes is all about protecting the market share and growing it.”

Kapur puts it in perspective, “Tatas are a committed organisation and they have deep pockets,” he said. “I am sure they have a strategy in place in terms of aircraft maintenance, HR practices, network planning, turnaround time and profitability. But what is missing is a communication strategy. Air India is in the public arena and a lot of your stakeholders are potential passengers. And they want to know, ‘Should I be flying Air India or not?’”

TEST MATCH, NOT T20

It is not for want of trying, but the airline is saddled with old aircraft that desperately need repairs and makeover. Wilson had told THE WEEK a few months ago that with new Airbus A350s being added into the fleet, old planes would be sent for retrofitting. “The process includes painting with the new branding and livery, and changing the interiors and seats. So we have to see what value we get. The really old planes will not go for this and will be retired from service,” he said.

That, however, will take time, and until then, the management has been playing with the frills―changing the logo and livery, a new set of crew uniforms designed by Manish Malhotra and overhauling the airline’s digital infra.

The digital upgrade includes a new app and revamped website, an iPad app for cabin crew and facilities like baggage tracking and WhatsApp virtual assistant for passengers. “In the last one year, we have taken several initiatives to enhance customer experience, including digital channels, airport and inflight services and contact centre,” said Rajesh Dogra, chief customer experience officer, Air India.

Air India has been working on improving its frequent flyer programme ‘Flying Returns’, adding in anything from Legoland to cruise lines and rail systems in Europe where points can be used and bookings done seamlessly. The Maharaja lounges at Delhi T3 and New York’s JFK are also set to be refurbished into signature lounges. “We are confident that the modern, world-class look of Air India will appeal to our guests globally and serve as a strong reminder of all the remarkable changes that have come or are to come to their Air India experience,” said Wilson.

WHOSE AIR INDIA IS IT ANYWAY?

Air India may still surprise us after the five-year transformation is complete in 2027. But that does not mean that India’s aviation market will be its for the taking.

The intense competition, both domestic and international, is unlikely to ease up, despite the fact that the number of domestic airlines can be counted on one’s fingers. While airlines from the Middle East and the likes of Turkish Airlines are eyeing the growing and lucrative international market, runaway market leader IndiGo is in no mood to give way at the domestic front.

Air India’s strategy is to speed up the Vistara merger to create an impression of better quality levels in its full-service offering, even while shoring up its presence in the low-cost space by aggressively expanding Air India Express. IndiGo has already responded with beefing up its international network and codeshare partnerships aiming to become India’s global carrier, a position that conventionally belonged to Air India. It has also announced a full-service business class offering, ending any hopes that Air India will have monopoly in the premium full-service segment within the country.

Also, the globetrotting connoisseur with rarefied tastes―the typical image of a passenger from Air India’s glory days―has changed. Millennials and Gen Z travellers are not really bothered with the champagne’s temperature or the cutlery on board. If at all, they only have negative connotations of the airline, unlike an older generation who associate AI with royalty, national pride and jet set glamour. It will be tough to win them over when stories of bad passenger experiences abound on social media.

Tail wind

By K. Sunil Thomas

If money is the bottom line, Air India’s new management does have reasons to be happy. The airline is still in the red, but the losses have narrowed, showing that there is hope left for the Maharaja.

The overall losses of all four airlines of Tata came down from about Rs15,000 crore in 2023 fiscal to just above Rs6,000 crore this year. For Air India alone, the losses have come down 60 per cent from around Rs11,000 crore in 2023 down to Rs4,444 crore this year. The increase in turnover was an impressive 24 per cent to more than Rs50,000 crore!

How did the airline manage this feat, considering the fact that it has been labouring under a mountain of debt? “They maximised their load capacity, getting as many planes as functional as possible, and increased routes, seats and the load factor,” explained aviation expert Sidharath Kapur. Airfares were also rationalised, making Air India offer, in many instances, more competitive fares than the market leader IndiGo.

The airline has also been working on a two-pronged strategy of cutting expenditure where possible, especially on the administrative side, even while maximising add-on revenue, on anything from seat selection to excess baggage. While passengers may crib that Air India is going the IndiGo way by charging for extra weight, “all this amounts to revenue”, according to an industry insider.

Kapur feels that if Air India manages to stay on this course, it might even turn profitable in a few years. Meanwhile, sister-airline Air India Express has flown into the red posting losses of Rs163 crore―ironic because even during the dark days of bureaucracy-run inefficiency, it had mostly made profits. This could be attributed to its aggressive expansion domestically to take on IndiGo.