IT’S A BUSY DAY, despite being a Sunday. In between finishing some pending work on the computer and house chores, I decide to order in brunch. On the food delivery app on my phone, a little box on the screen catches my eye. Titled ‘Your Usual Order’, it showed a restaurant called Dhaba By Eleven, and a Gosht Keema Mutter from there has already been added into my check-out cart.

How very convenient, one might think, except I have absolutely no recollection of this restaurant. I trawl through my past orders and discover an obscure order I had made from this restaurant once, about six months ago!

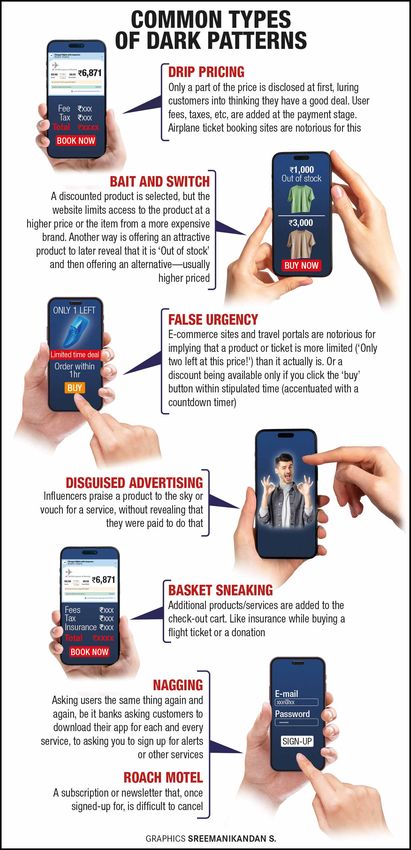

This sly trick from a food aggregator app is just a drop in the ocean of deceptive marketing and sales tricks that millions of Indians fall prey to every day on the internet. Ever seen the countdown timer telling you a particular discount is available only if you click on it within the ‘deadline’? Or an airline booking site offering you a great deal, but, at the last stage, adding hidden fees like taxes, user fees and what not? Or a platform which makes discontinuing a subscription the stuff of rocket science?

All these come under the umbrella of ‘dark patterns’, a term coined by London-based user experience designer-turned-activist Harry Brignull, to describe the treacherous ways of website and interface design that fool customers. (Examples of dark pattern, though, can be found in the physical world, too.) And, as more and more Indians, particularly those who are not proficient in English or marketing jargon, start using the internet and start ordering from all the Flipkarts and Amazons of the world, they face the risk of being fooled into losing money, personal data and privacy. (Flipkart told THE WEEK that the company had nothing to say after a questionnaire about dark patterns was sent).

Shekhar Kumar, a Bihari working in an ad agency in Gurugram, has tales galore about the dark patterning he has been subjected to. The latest came from a popular YouTube motivational speaker. “The YouTube ad for a business development course I was interested in was offering a 099 signing up offer, only available for the next 10 minutes,” says Kumar. He could not sign up at that moment for some reason. But when he went back to the site after a while the offer was still there, this time also with a deadline of 10 minutes!

“Essentially, anything that takes away consumer autonomy, free will and informed decision-making power can be qualified as a dark pattern,” said Karim Rizvi, founding director of The Dialogue, a public policy think-tank. “They are a growing concern.” The worries over the trend started building up in India in the past few years, after cheap data opened the gateways to an explosion in the use of e-commerce, apps and social media.

For many e-commerce players, it might be all par for the course, all in a day’s work. But as dark patterns become too commonplace, governments across the world are stepping in.

The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) noticed a marked rise in dark patterning in 2023. A survey by consumer research platform Dovetail says that at least 40 per cent of customers had lost money because of dark patterning. FTC is now taking cognisance of dark patterns and imposing penalties, while California and Colorado states have rules in place prohibiting businesses from engaging in dark patterns. In Europe, the EU’s Digital Services Act specifically outlaws the use of dark patterns.

Recently, India’s Central Consumer Protection Authority came out with a set of guidelines effectively banning the use of 13 marketing practices which it termed as ‘dark patterns’. The government intends to ratchet it up further by launching a mobile application that can alert consumers when online platforms use dark pattern tricks to lure internet users. Users will just have to have the app installed on their devices―it can automatically detect dark patterns on leading e-commerce sites and alert the users, who can, if they wish so, complain to the consumer protection forums.

“The specific regulation and restriction of dark patterns by the Centre is a welcome approach, especially since dark patterns pose a threat not only to society at large but also specifically to vulnerable users such as lower middle-class people, children and the elderly, owing to their limited digital literacy,” said Ranjana Adhikari, partner with the leading law firm IndusLaw.

The Advertising Standards Council of India (ASCI) did a study on the issue two years ago, pointing out how the “Indian consumer is not immune to dark patterns, and as online commerce grows, this is an increasing area of consumer vulnerability”. ASCI had categorised dark patterns as a violation of the Consumer Protection Act.

After this, the Department of Consumer Affairs summoned cab aggregators like Uber and Ola to come clean on their charges and algorithm, following complaints from user fares changing after the start of the ride and some other issues.

Back in 2021, ASCI had asked social media influencers to disclose promotions to address the issue of disguised ads. It found that around 30 per cent of ads it processed in 2021-22 were paid ads disguised as content by influencers―a kind of dark pattern that extended from cryptocurrency to personal care. Now, with a specific guideline against dark patterns and an app to detect them, would they be reined in? Not necessarily.

“In the most recent version of the consumer authority’s guidelines, there is no penalty clause,” said Disha Verma, associate policy counsel with the Internet Freedom Foundation. “So the law is not really a law.”

Another vexing issue is jurisdiction. While the consumer affairs ministry seems to have taken the initiative, who has the authority to monitor dark patterns in various sectors? Recently, for instance, the insurance regulator IRDAI notified that the dark pattern of adding travel insurance as a default option by travel portals was not lawful. Does this mean sites should be regulated subject-wise? A financial portal to be dealt with by the Reserve Bank, or an unfair trade practice by the Competition Commission, for instance? Or is it better served by the consumer affairs ministry? Or will the digital acts under process by the IT ministry, like the Data Protection Bill or the Digital India Act, show the way forward? It is not clear.

While Verma feels that self-regulation can “help keep the marketplace in check, and afford them innovation and design creativity”, Madhu Vishwanathan, associate professor (marketing) and research director at Indian Business School Institute of Data Science, Hyderabad, feels “there should be a stick in place”.

“It is a cat-and-mouse game where as regulations change, firms adapt and come up with newer practices that are going to work on the consumer psyche or exploit the biases that consumers have,” he said. “The government will find it hard to implement this law in full. It is easier to police the big companies. But once you start going into the smaller or the medium-size companies, where the practices are much more prevalent, it will be hard to police.”

Dark patterns stretch into the offline space, too. Take DigiYatra, for instance. Many airports reserve multiple entry gates for passengers who have signed up for DigiYatra and cause artificial rush at the remaining gates. It forces passengers to sign up for DigiYatra scanning.

“Government is the biggest entity engaging in dark patterns,” says Verma, pointing out the rollout of APAAR-ID card, an Aadhaar-like repository for academic records that schools are pushing students into taking, and how it is next to impossible to delete your Aadhaar or Covid-19 vaccine details. “If we were to make a consumer first awareness campaign about dark patterns, it can’t be just online. It has to have at its core consumer rights empowerment and the understanding that it is your right to say no, that it is your right to not be put in a position which you can’t escape from.”