The 278km-long expressway connecting Colombo in the east with Kataragama in the south is lined by idyllic beaches and imposing mountains. It runs south from Colombo, tracing Sri Lanka’s southwestern coastline till it reaches Tangalle in Hambantota district, from where it arches inward to Kataragama, about 30km inland.

Tangalle is a small fishing port. A narrow road off the expressway takes you past posters of President Maithripala Sirisena and former president Mahinda Rajapaksa, to a bronze statue of Dudley Senanayake, Sri Lanka’s second prime minister and founder of the ruling United National Party. Senanayake stands tall on a pedestal, pointing at Carlton House, a manor house across the street painted forest green.

It is 8am on a Sunday, and a crowd has gathered outside the Carlton House gates. As they wait to go in, people turn in their cellphones and take tokens, and are frisked by armed guards and policemen. The visitors do not seem to mind the security measures; they are here to see their favourite leader.

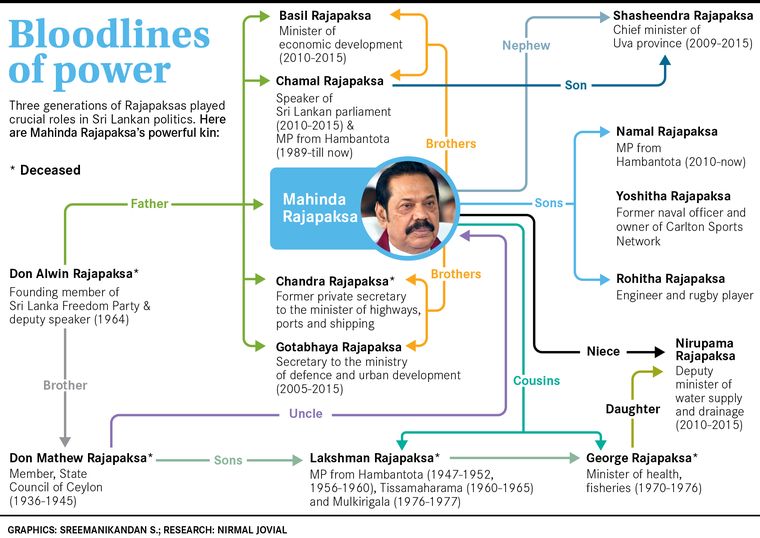

Carlton House has long been the seat of the Rajapaksas. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s grandfather, father and uncle were headmen and prominent politicians in Hambantota, but the former president towers over all of them in popularity and charisma.

Rajapaksa is all smiles as he enters the visitors hall at Carlton House. He is clad in a white dhoti and kurta, with his trademark brown shawl around his neck. The shawl is a legacy from his uncle. It was Don Mathew Rajapaksa, who was state councillor in the 1930s, who first took to wearing the shawl to represent the main crop of Hambantota—the earthy-brown finger millet.

Earthy, however, is not the word one would use to describe Mahinda Rajapaksa. He sits on a huge, burgundy sofa and greets visitors with clasped hands, showing the gold rings that adorn almost all his fingers. He smiles as young men pump their fists and cry, “Mahinda mahtya [Mahinda, my boss].” Beside him is G.L. Peiris, who was minister of foreign affairs when Rajapaksa was president. Even as the duo is deep in talks, men and women come and fall at Rajapaksa’s feet, and receive gentle smiles of acknowledgement.

Last October, Rajapaksa tried to return to power by toppling Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with the help of Sirisena. The attempt failed, but Rajapaksa still remains the most powerful man in Sri Lankan politics. His next mission is winning the parliamentary election, expected to be held later this year. “The Sirisena-Wickremesinghe government has failed the country,” he tells THE WEEK. “I am determined that I should save the country and the people.”

He invites us for breakfast. Milk rice cake, string hoppers, pol sambol and seeni sambol are served. “It’s pure vegetarian, as it is poya today,” he says. In Sri Lanka, every full moon day is known as poya, and it is a time for temple visits and religious observances. At Carlton House, poya involves opening the gates for the public, serving them food and giving them an audience with Rajapaksa. Later, the Rajapaksas would listen to an hourlong bana (Buddhist sermon) and offer prayers with the public.

Rajapaksa gets up from his sofa as he sees a BMW approaching the portico. He walks down the steps with his hands folded and welcomes the mahanayake thero (a high-ranking monk) of the Asgiriya chapter. A narrow white carpet is rolled out from the portico to the small Buddha temple behind the house. Led by the mahanayake, Rajapaksa walks to the temple. A traditional music band flanks him and a huge, colourful umbrella is held above his head by a band member. Rajapaksa’s wife, Shiranthi, and his son and political heir Namal Rajapaksa join him at the temple. They, too, are dressed in white.

The mahanayake takes his chair on a pedestal. Shiranthi, Namal and others sit on the floor. A floor-level sofa is laid for Rajapaksa. Hands folded and eyes closed, he begins chanting as the mahanayake begins the prayer.

“Rajapaksa is our hero,” says Bandini Sisira, who is a regular at the poya programmes at Carlton House. “Peace returned in Sri Lanka because of him. I believe he alone can rebuild the country now. Without him, there is no Sri Lanka.”

Rajapaksa was born at Weeraketiya in Hambantota on November 18, 1945, as the third of nine siblings—six brothers and three sisters. He studied at Richmond College in Galle, and Nalanda College and Thurstan College in Colombo. After graduating from Colombo Law College, he began practising law.

In 1970, when he was just 24, Rajapaksa was elected to parliament from Beliatta, which was once represented by his father, Don Alwin Rajapaksa. In 1977, when he lost a parliamentary election, he shifted his legal practice to Tangalle, which helped him build a support base. He was reelected to parliament from Hambantota district in 1989, and has never lost an election since.

Rajapaksa led the Sri Lanka Freedom Party in the 2015 elections, and is now part of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramunwea, formed in 2016 by his younger brother Basil Rajapaksa. The SLPP swept the local body polls in February last year.

“Mahinda is the only charismatic leader in our country. He is the leader of the masses and he can lead anyone to victory,” says Dilip Fernando, a Rajapaksa loyalist who recently became municipal councillor in Colombo.

Rajapaksa values loyalty and, despite his charm and pleasing manners, does not tolerate betrayals. A case in point is what happened to Sarath Fonseka, the former army chief who challenged Rajapaksa in the 2010 elections. Fonseka was stripped of his rank, pension and medals, and was jailed after being barred from contesting elections for seven years. Sirisena, who had joined hands with Wickremesinghe in 2015 to keep Rajapaksa out of power, seems to be the only one who has managed to mend fences with the strongman from Hambantota.

In an extensive interview to THE WEEK, Rajapaksa spoke about the political troubles in Sri Lanka, how he plans to resolve them, and what his priorities would be if he returns to power. Excerpts:

That was certainly not a successful government. The UNP (Wickremesinghe’s United National Party) was running the show and the UPFA (Sirisena’s United People’s Freedom Alliance) was mostly a passive partner. After leaving that government on October 26 this year, the president explained to the public how frustrated he was with the UNP. Even when he was in partnership with the UNP, we could see from the outside that there were serious disagreements between the partners in the government. The appointment of a commission of inquiry to probe the Central Bank bond scam of 2015 and the abolition of the UNP’s economic affairs committee were signs of that. The president has publicly said that he is writing a book about his ‘failed political marriage with Ranil Wickremesinghe’. That says it all.

In your speech in parliament on November 15, you said the UNP had actually failed the country, citing the rupee’s fall and the increase in prices. Do you think these factors have affected the country more than any other issue in the recent past?

Of course. In January 2015, what we handed over to the UNP was a very stable economy. Between 2006 and 2014, my government increased the per capita income of this country threefold in US dollar terms. The economic troubles that the country faces now is due to the foreign currency borrowings of the past three and a half years. They borrowed $20.7 billion, and got caught in a cycle of borrowing, repaying and borrowing to repay. There has been very little development work in this country since 2015, except for what has continued from our times. So what Sri Lanka experienced after 2015 was an economic catastrophe. The LMD-Nielsen Business Confidence Index shot up the moment I was appointed prime minister on October 26, because the business community is well aware of the difference in the way my government managed the economy.

Do you think that Wickremesinghe let down the country and its people?

Very badly. There was a palpable feeling of relief in this country after he was removed from power on October 26. The president broke up with the UNP because they were ruining the country. If he had remained in that coalition, the president, too, would have had to shoulder the responsibility for what was happening to the country.

You have been demanding elections, saying the UNP fears elections. Are you sure of a comeback?

The result of the local government elections in February this year made it clear that the SLPP (Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna) was by far the largest political party in the country and a coalition with the SLPP will win any future election. That is the very reason the UNP and its allies are so reluctant to face an election. No self-respecting political party will go to court against the holding of a general election that has already been declared. But that happened in Sri Lanka.

In the recent local government polls, your party won majority votes. Does it mean that the people are with you?

Absolutely. You have to realise that the SLPP defeated established political parties to come out on top. Together with the SLFP (Sri Lanka Freedom Party) and our allies in the north and the east and the hill country, we command a very comfortable majority.

Why did you choose to walk away from the SLFP, although Sirisena appointed you prime minister? Are we going to witness a three-way fight between you, Sirisena and Wickremesinghe?

In 2015, after the majority group of the UPFA (United People’s Freedom Alliance) decided to sit in the opposition, almost all of them were removed from their constituencies and replaced with other organisers. So there was a need for a different setup, with new constituency organisers and a party machine to face the next election. In any case, the SLFP has, since the 1990s, contested as part of a coalition. There will be no three-way contest. It will be between the UNP-led coalition and our alliance of political parties, including the SLPP and the SLFP.

Will you lead the SLPP in elections in 2019?

Of course. I intend to spearhead the election campaign of the coalition in which the SLPP will be the major partner.

You completed two terms as president. Will the SLPP make you its presidential candidate?

The SLPP and the joint opposition will make the final decision as to who will contest the next presidential election.

Do you plan to announce a presidential candidate acceptable to all?

Yes. The next presidential election will have to be held before December 9, 2019, according to our constitution. We have less than a year for the election process to start.

Will the candidate be from your family or an outsider?

It could be either. As I said, the party will select the best candidate.

Your return to power in Sri Lanka seems imminent. What do you have to say?

The people are waiting for us to come back to power. After an election, that is. The government that was formed after October 26 was just an interim arrangement [tasked to serve] until the conclusion of the general election. Since that election cannot be held, a change of government will take time, but it is inevitable.

What do you have to say about the UNP fighting Sirisena’s decision to dissolve parliament?

That shows how shameless they are. Once a general election is declared, any self-respecting political party would contest the election, instead of petitioning court to have it halted. They delayed the local government election by more than three years and tried to put them off indefinitely by approaching the courts, but that was prevented by the intervention of the chairman of the election commission. Elections to the provincial councils have been delayed by more than one year and three months. Now they have managed to prevent a general election.

What is your opinion on Sirisena as president? He once betrayed you, but you seem to have accepted him now despite his shortcomings.

Maithripala Sirisena has been a friend and colleague for decades. We shared the same political ideology. He left us over certain differences. These things do happen in politics. He has now rejoined his original camp, which is more in alignment with his own political outlook. Both sides will forget the past and look to the future.

What do you think about rumours that India’s Research and Analysis Wing was plotting Sirisena’s assassination? Do you feel that the lives of Sri Lankan political leaders are under threat?

The evidence seems to show that there certainly was a plot to assassinate not only the president but also my brother Gotabaya. I cannot say anything about any involvement of the R&AW in that conspiracy, because I have not got any information to that effect. But, it was supposed to be carried out by the underworld, which became very powerful in this country after 2015.

Will the SLPP join hands with the SLFP to fight the elections?

Sirisena had already hinted at this possibility.

Yes, an alliance will most probably be formed. In any case, both groups were part of the same political party not so long ago.

Are you willing to work with Sirisena?

Yes, there is no reason why we cannot work together. We worked together before 2015 and we will work together after 2018.

Most Sinhala people in Sri Lanka say the country needs a strong leader like you to take it forward in terms of development.

Every country needs a strong leader. The reason why we have a large support base is because of what we achieved in the nine years.

The minorities are worried that you represent Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarianism.

That is a label pasted on us by our political rivals. Of all those who have led this country since independence, my family is the most multicultural. There are people of all major religions and ethnicities in my family circle. One of the reasons why this majoritarian label has stuck is because we defeated the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) militarily. But in that, we had no choice. We cannot allow terrorism in this country.

Do you think there has always been a campaign against you to bring you down politically?

Yes. There are elements, both local and foreign, who do not want to see me coming back to power. These are elements that seek to control Sri Lanka’s destiny. The people of this country see me and the political movement that I lead as the only force capable of preventing foreign domination. We are now in a struggle against neo-imperialism.

What are your plans for Sri Lanka when you return to power?

Our main concern is the economy. There is a need to control the debt crisis that the UNP-led government created. The next priority will be to consolidate, and to make operational, the development projects that we initiated when I was in power.

You recently visited India. Was it to smoothen your relationship with India?

I think our relationship with India is now beginning to look more like what it should be. In 2014, certain misunderstandings emerged between the newly elected governments [in both countries]. That is something that should not have happened.

In your speech in parliament, you said the speaker is influenced by western forces. Is India also part of this? Is India in anyway influencing Sri Lanka politics?

I think India kept away from the recent crisis. We are neighbours. We have to work with each other with whatever government that may happen to be in power. I think that was the stand adopted by India. The fact that some western powers were heavily involved in the recent political crisis in Sri Lanka was quite obvious. They never tried to hide the fact that they are interfering in the internal affairs of Sri Lanka.

A few years ago, you said in an interview that India played a major role in bringing the opposition together in Sri Lanka. Does that stand true even now?

No, I don’t think India would be involved in anything of that nature now.

In the past, you were perceived to be closer to China than India. Your September visit to India was a success. Although your visit was unofficial, you had a meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Has anything changed?

I have always said that India is a close relative and that China is a friend. I think our bilateral relationship with India has improved enormously. It is not correct to say that I have been closer to China than to India. Even when it came to the building of the Hambantota port, I first put the proposal to India and turned to China only when India did not show any interest.

Do you think you could have done much better in the deal for Hambantota and Colombo port projects?

Absolutely. My government never had any plans to privatise the Hambantota port. I can tell you authoritatively that China never asked Sri Lanka for the Hambantota port on lease. It was Ranil Wickremesinghe who went to China and pleaded with them to take the port. Wickremesinghe has a compulsive tendency to sell government property. Around 2003, he sold a part of our petroleum corporation to the Indian Oil Company for no logical reason. Now he has sold the Hambantota port. One of the main reasons why President Sirisena withdrew his MPs from that government in desperation was because he thought there would be no government property left in the country if things had continued the same way.

Wickremesinghe’s dismissal was criticised by several world powers, including the US and the European Union. Was not the move against the spirit of democracy?

When the UPFA group left the government on October 26, the cabinet stood dissolved because that cabinet was formed under special provisions in the constitution relating to ‘national governments’. When this national government ceased to exist, some government MPs came over to our side and we became the largest single group in parliament. Since 1994, we have had a practice where the president invites the leader of the largest group in parliament to form a government, if no one has a clear majority. So, on October 26, I was the natural choice to become prime minister. Wickremesinghe was not really sacked. His government ceased to exist because the UPFA withdrew from the partnership. Some western powers back Wickremesinghe because he is completely subservient to them. Wickremesinghe does not seek the approval of the people of Sri Lanka; he seeks approval from the western embassies in Colombo.

Is Wickremesinghe too close to India? Do you think India is overtly interested in Sri Lankan politics?

I do not know what Wickremesinghe’s relationship with India is. If he is as close to India as some people say he is, how is it that he gave the Hambantota port to a Chinese company on a 99-year lease, knowing fully well that it would cause anxiety to India? We have had situations where India did get involved in Sri Lankan politics. According to my understanding, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and his successors and others who led India right up to the beginning of the 1980s had a policy of noninterference—which is why the bilateral relationship was quite sound during the first three decades after independence. I think we should study the past and see how our predecessors on both sides of the Palk Strait succeeded at that time, and make that our guide for the future.