Watching Prime Minister Narendra Modi at work in Varanasi is a bit like watching a tiger in Ranthambore. The master campaigner is in his element. He has his ear to the ground. He can pad softly when needed and crash through the dry leaves when the mood is on him. He can remain silent. He can call for love. For war. And, then there is the retinue. The watchers in the trees, calling out warnings. Then, those who rush in panic through the undergrowth. There are the porcupines, whom even the striped-one shuns. The scavengers giggle in the shadows. Too scared to look him in the eye, but too dependent on the pickings. It is a regular jungle out there. And with 2019 upon us, it will get wilder. And it all has begun in Varanasi, home of Mahadev, the God of Gods.

Kashi. Banaras. Varanasi. The City Eternal. Pracheen (ancient) is the prefix applied to it and to many things within. How old? The standard answer is a tired quote attributed to Mark Twain: “Banaras is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend and looks twice as old as all of them put together.” Through the ages, seekers have been drawn to this wellspring of spirituality. You run into them in the slim and sinuous lanes. By the eternal funeral pyres at Manikarnika Ghat. In the Ganga, when the dawn is cold and grey. At dusk, when the blazing aarti salutes the sacred river at Dashashwamedh Ghat. In the beginning. At the end. And every time in between, the seekers are a constant.

Yet, one does not expect to meet truth in Varanasi. The city embodied post-truth before the thought was even born. One goes there by faith, not for facts. It is a city of greys, of contradictions. Many holy cities in north India frown upon non-vegetarian food. But Mahadev’s city takes it in its stride. Major hotel brands have properties here. As one drives in from the airport in Babatpur, one can see apartment stacks rising above a city that was once low-rise.

Yet, in the old quarter, it is not uncommon to find walls made of thin Lakhori bricks from the Mughal era. On the ghats, the Naga sadhus sleep around ritual fires in makeshift tents. There is a Kashi that buys O-Baama underwear, eats at Sanjay’s “Suoth Indian Food” and shops at Hangers Cloth Shop (Tagline: Work. Play. Hang.) The local resident, aka Kashivasi, accepts both worlds. Just as he accepts the Ganga’s many avatars, its summer grace and rain-fed rage.

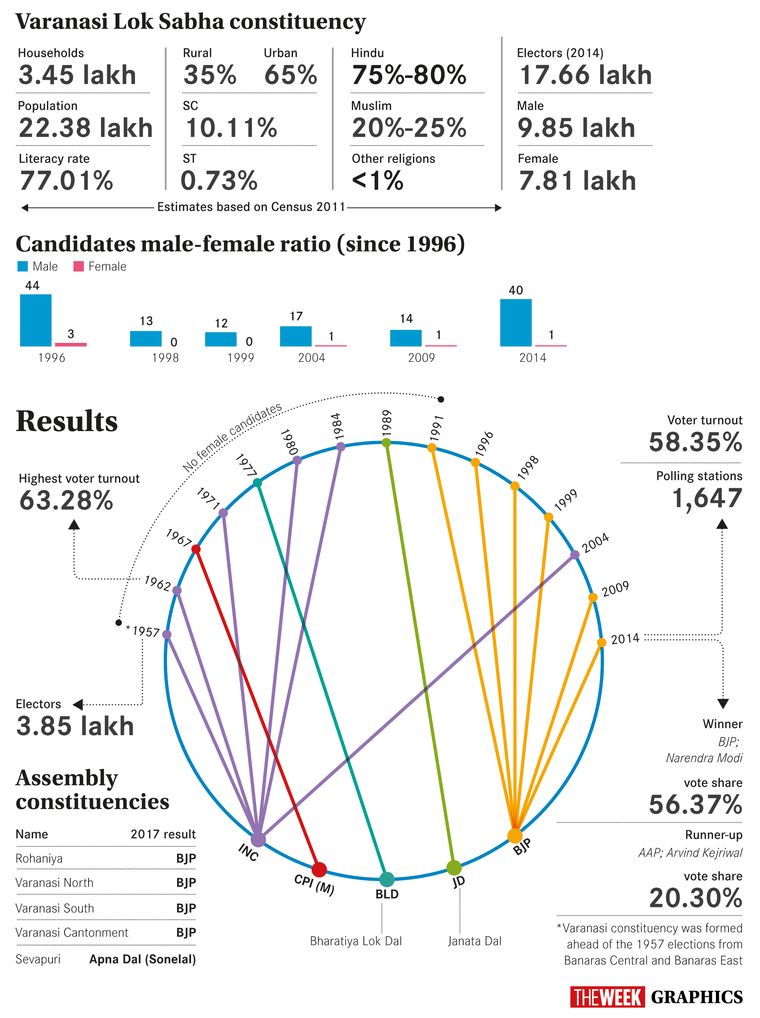

Into this mystical stage, Modi was parachuted in 2014. It would have been tough to find a better Lok Sabha seat for the Hindu hruday samrat than constituency No 77. Varanasi was not always a BJP seat. Since 1957, it has elected the Congress six times; the biggest name among those being Kamalapati Tripathi. The Bharatiya Lok Dal (Chandra Shekhar!), Janata Dal and the CPI(M) once each. And, the BJP six times. Since 1991, it has stood solidly behind the BJP. But, bowled a googly in 2004 and elected Rajesh Kumar Mishra of the Congress. So, in 2014, both Modi and the BJP wanted more than one basket. Plan B: Vadodara.

This time, the grapevine says that the demands on him are more, and from the east. Pradip Purohit, MLA from Odisha’s Padampur, said in January that there was a “90 per cent possibility” of the prime minister running from Puri, famous for the Jagannath temple sacred to Lord Vishnu. The West Bengal BJP leadership wants him to run from Kolkata, to take the fight to Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee. Bihar, too, is keen on having him in Patna Sahib, Shatrughan Sinha’s seat (2009 and 2014). Gujarat wants him back, especially after the assembly poll scare in 2017. With the central leadership of the BJP keeping the cards close to its chest, all this is but speculation. But most Kashivasis are sure that if Modi contests from multiple seats, Varanasi will be one of them.

THE CAMPAIGN

At Modi’s rally in Audhe village on February 19, days after the Pulwama attack, the patriotism quotient was high. Every time the Doordarshan cameras ventured close to the crowds, the tricolour and BJP flags came out, accompanied by chants of “Pakistan murdabad”.

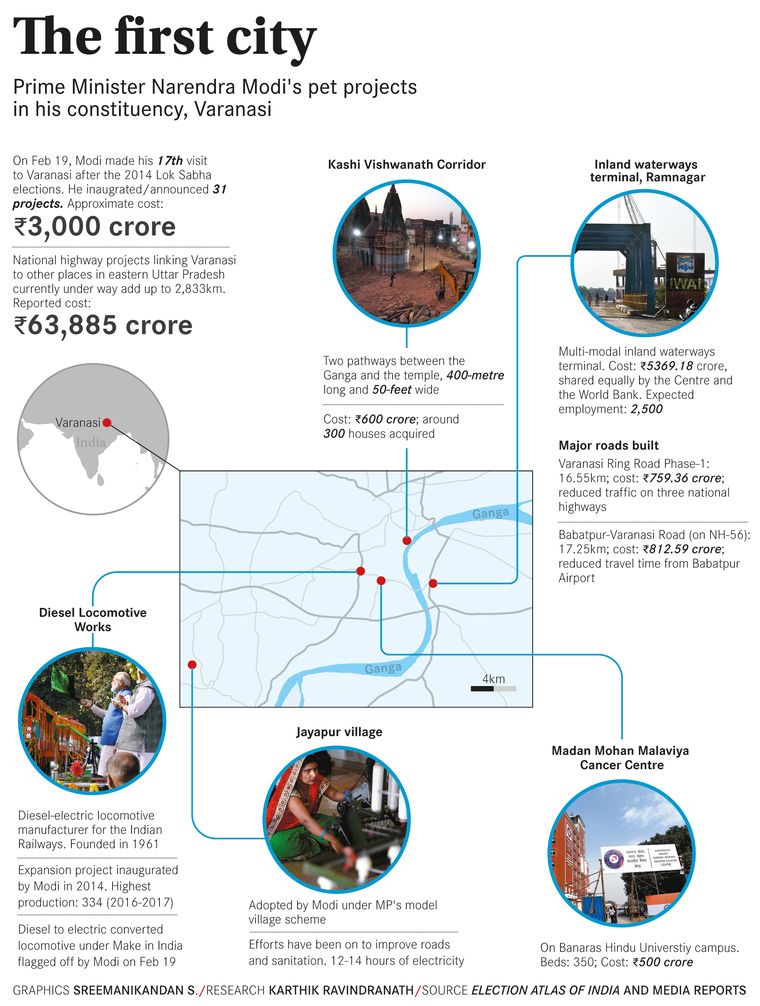

Even before Modi’s arrival at the venue, beneficiaries of various schemes were called on stage. Mostly poor women. “Amma, smile!” the emcee says encouragingly. “The photo will come out well. It is your opportunity to receive this from the lotus hands of the prime minister.” The digital screen goes live, showing Modi inaugurating the Mahamana Madan Mohan Malaviya Cancer Centre on the Benares Hindu University campus. In attendance are Uttar Pradesh Governor Ram Naik, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, Ratan Tata and BJP state president Dr Mahendranath Pandey.

As Modi leaves the hospital, the screen goes blank. Folk singers start a song about the Pulwama massacre. “Baramulla mein…(In Baramulla),” warbles the lead singer. The boys behind the press enclosure are confused for a moment: “Baramulla ki Pulwama? (Baramulla or Pulwama?)” An older man in a magnificent moustache calms them down: “Pulwama, magar zilla Baramulla (Pulwama, in district Baramulla).” Fact check: Pulwama is a district in itself; Baramulla is a border district. And they are separated by Budgam and Srinagar districts. The folk singers have now moved on to Uri and the surgical strike.

The digital screen now shows a clip detailing the projects that Modi undertook in Varanasi. “Like King Bhagirath’s efforts brought down the Ganga (from the heavens to earth), the prime minister’s efforts have transformed Kashi,” says the voiceover. “Vikas ki Ganga (The development Ganga).”

Closer to noon, Union Minister of State for Communications and Railways Manoj Sinha and Uttar Pradesh Deputy Chief Minister Keshav Prasad Maurya come on stage. The crowd cheers. Soon, Modi strides in. The crowd is ecstatic. The meeting gets under way in a jiffy. And, it is a class in efficiency. No flab.

But certain things remain the same. Like, Nehru-baiting. In his welcome address, Pandey says, “I met an old man who told me, ‘I have seen prime ministers from Nehru onwards, but I have not seen any other prime minister work so hard for the poor’.” And, acronyms. “Modi means Man of Developing India.” Pandey is the first speaker to raise the Shaivaite rallying call: “Har har Mahadev.” The crowd and dignitaries respond in unison.

In his speech, Sinha says, “The prime minister has made it clear that if the foundation stone was laid by us, we must inaugurate the project, too.” Most commendable, considering how government projects drag on. Sinha highlights two main projects: renovation of the Manduadih railway station and the conversion of diesel locomotives into electric at the Diesel Locomotive Works in Varanasi.

Adityanath’s speech is on expected lines, about how Varanasi was thirsting for progress and how Modi has fulfilled it. Like the others, he, too, makes a mention of the flagship projects, especially Namami Gange.

Then, Modi. The crowd adores him. Undoubtedly, there is no orator to checkmate him among politicians today. Though people call Adityanath a fiery orator, you must hear them in succession to realise how far ahead Modi is. The prime minister begins by paying homage to the Pulwama martyrs and tells the crowd that he is aware of their feelings and expectations. He says, “I have come to gather strength to pay back the debt we owe the martyrs, for which I need the blessings of Baba Vishwanath, Ma Ganga and all my brothers and sisters.”

Modi reminds the crowd that February 19 marks the birth anniversaries of Sant Ravidas and Chhatrapati Shivaji. It is also Maghi Poornima, the day of the last ritual dip at the Ardh Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj. He then goes on to talk in detail about the projects done in Varanasi. Then, comes the comment that went viral—about the questions raised by the opposition on the Vande Bharat Express breaking down on its inaugural run. Modi spins it as an insult to the engineers who designed and manufactured the train.

Is it right to insult the engineers?

No, the crowd roars.

Should we forgive those who insult our engineers?

No, the crowd roars.

This is the BJP’s star campaigner in action. He then lays the foundation stones of 39 projects worth around Rs 3,000 crore. The end is dramatic: “Roll your fists with all you strength. Raise your arms high and say… victory to Mother India.” The marquee shakes with the crowd’s response. It is difficult to remain unmoved. And, this is how the campaign for the 2019 Lok Sabha polls is going to be.

It is going to be a tsunami of patriotism, hyper-nationalism, payback and hindutva. All successful development projects will be advertised heavily. The campaign will play up the opposition’s lack of a central figure. It will sweep aside the rising prices of fuel and food. Black money and corruption charges will be just garnishing.

IN VARANASI

The road from Lal Bahadur Shastri airport in Babatpur to Varanasi city is a four-lane blacktop with three flyovers. Shatrugan Prasad, a driver, says that better roads have improved his income and quality of life. “Earlier, I used to take up to two hours to get to the city from the airport,” he says. “Now, I am there in 45 minutes or so. It has also made life easier for farmers who bring produce into the city. True, people lost homes and shops when the road was widened. But, they were all paid more than the market rate.”

The question that came up most was, “Whom are you comparing Modi with? Joshiji?” Varanasi had elected former Union minister Murli Manohar Joshi in 2009. The general verdict is that Modi has done much better than Joshi. And, the Kashivasi does not think that the Samajwadi Party-Bahujan Samaj Party combine or the Congress can do more for them. Vijay Kumar, who runs a secondhand bookshop in Lahurabir, says, “Assume that a child is born each in your home and in the prime minister’s. Wouldn’t the prime minister’s child have more opportunities?”

A few metres away from Kumar’s shop, a man pees into a stack of bricks. Despite the Union government’s push against open defecation, it continues to be a reality in Varanasi. The city is not clean by any measure. However, residents say that the Swachch Bharat initiatives have improved sanitation. Sweepers clad in orange T-shirts emblazoned with the Swachch Bharat logo can be seen at work even in the narrowest of lanes in the old quarter. By the ghats, you will run into the Namami Gange workers, scooping up flotsam from the river and scraping up everything from chewing gum to cow dung and human excreta from the stone steps.

Next stop: Ramnagar, home of the flagship multi-modal terminal. Work on the terminal began in June 2016; Modi inaugurated it on November 11, 2018. River ports were never really explored in India and Union Minister Nitin Gadkari has been going all out to change this. Started under the Union government’s Jal Marg Vikas Project (JMVP), the terminal is connected to Haldia, West Bengal. In addition to generating employment, river ports are expected to take heavy and hazardous cargo off the highways.

The terminal’s first shipment came before its inauguration. In October 2018, PepsiCo sent 16 shipping containers of fizz and chips on the MV RN Tagore, a vessel owned by the Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI). The vessel completed the 1,390km-long journey in around 10 days. The RN Tagore returned to Kolkata with fertilisers from IFFCO’s Phulpur plant. Last month, the game got serious when shipping biggie Maersk ran a test consignment of 16 empty containers to Kolkata.

However, the project’s biggest challenge is the presence of around 16 pontoon bridges between Varanasi and Patna. “These bridges are there for around six months, and are beached during the monsoon,” said a source who did not want to be named. “These have to be dismantled to let any vessel pass. Sometimes, one might be held up for a day or two. Perhaps, IWAI vessels have priority passage. But, it is not smooth sailing as it is made out to be.”

Though inaugurated, the work on the terminal is far from complete. The operational end is in place, the pier with two Liebherr 180 movable harbour cranes. Everything else is under construction.

After Ramnagar, we cross the river back into Varanasi and visit the Homi Bhaba Cancer Centre (HBCC) in Lahartara. The old Indian Railway Cancer Institute and Research Centre was handed over to Tata Memorial Hospitals, and the refurbished hospital was formally opened in May 2018. The project is one half of Modi’s plan of making Varanasi a hub for specialised cancer care. The other half is the Mahamana Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya Cancer Centre (MPMMCC).

HBCC is regarded to be the crown jewel among Modi’s projects in Varanasi. The hospital is as neat as a pin and is run with typical Tata efficiency. Rajendra Prasad Jaiswal, chief administrative officer of HBCC, says, “We serve a very needy community. Rural Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and even parts of Nepal. Quacks diagnose some people with cancer. We sometimes find that the case is benign. You cannot imagine the patient’s relief. These are people who do not even have money for the train fare to Mumbai. Forget staying and getting treated at Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai.”

The Tata Memorial Centre is administered by the department of atomic energy, which in turn is under Dr Jitender Singh, Union minister of state for the prime minister’s office. So, the buck stops at Modi’s desk. That kind of oversight has definitely smoothed things in Varanasi.

At MPMMCC, which is within the Benares Hindu University campus, we were denied entry by the Uttar Pradesh Police citing safety reasons. The centre had been inaugurated the previous day by Modi, but it was evident that the work was still on. Men in hard hats were running around, and the roar of power tools could be heard in the background.

The tender application which was closed on January 1, 2017 gave the builder 30 months to complete the Rs250-crore building. Even by the tightest deadline, completion can only be expected in June-July this year. But the elections will be over by then, and Modi will not be the first or last politician to inaugurate a project that is almost done.

The picture is not all rosy. Flash points have developed since 2014. Our next visit sees us walking from Maidagin via Bansphatak Road to the maelstrom that is Godowlia Chowk. Humanity pours from all sides. From there, the road leading to the Kashi Vishwanath temple is a river of people, cows, scooters, cyclists and monks in ochre.

After many a twist and turn, we end up in what used to be Lahori Tola. This area is a warzone. Brick dust swirls in the air. You feel like you are in a football field hemmed in by ancient structures. Just that there is a temple sticking out of the field here and there. Homes are being pulled down and carted away by the tractor-load. This is Varanasi’s showpiece project, the Kashi Vishwanath corridor connecting the temple with the Ganga at Lalita Ghat.

At one end of the field stands the temple and the Gyanvapi Mosque. Work does not happen by day, because it is tough to navigate the tractors through the milling crowds. Nights are filled with fiery lamps, rising dust and the roar of earth movers. We meet two supervisors who are working on the project. They are reluctant to give names. X says, “These old buildings were ready to collapse any time. The government paid them well. The ones holding out are doing so for more money.” Y adds, “Who would want to live like this in a lane which gets blocked when a bull passes through it? People are resistant to change, aren’t they?” They say they have not seen plans for the corridor. The plan is with Vishal Singh. It is a name we will hear spoken many times. Sometimes in respect, sometimes in rage. He is secretary, Varanasi Development Authority.

Eventually, we end at the doorstep of Rajkumar ‘Bhayyoji’ Kapoor, 63, once a seller of Banarasi silk saris and owner of a guest house. His three-storey house is crumbling. “They are building this corridor to help pilgrims?” he asks. “Did pilgrims ever complain? This land is being acquired for private players. Come back in two years and see. For these businessmen, people like me who grew up in the lap of Ma Ganga and in the shade of Lord Vishwanath are being chased out. Can you compensate me? Can Vishal Singh? Can Modi?

You must believe me when I tell you that tens of temples have been pulled down to make this corridor. I can prove it. And more than 200 homes have been pulled down here. Each with multiple families. Modi dare not ask these families for votes.”

In the middle of the corridor stands the Vriddh Sant Sevashram, a home for old monks. It will be pulled down one of these days. At the door, Ish Chaitanya, a 70-something monk from Gorakhpur, is sitting among bundles wrapped in cloth. He is leaving. Chaitanya’s voice quivers, “I came here to die in the lap of Ma Ganga. This is a pro-Hindu government only in name.”

In October 2018, Hindi-speaking migrant workers were forced to flee Gujarat after a Bihari man was accused of raping a child. The backlash was felt in Varanasi, when the newly formed UP-Bihar Ekta Manch splashed posters saying that if Gujaratis ostracised north Indians, the Kashivasi would shun Modi. The protest was quickly contained. But, it is far from dead.

Indramani Tiwari, a leader of the Manch, says, “Last year, we agitated and submitted memorandums because the Varanasi MP is from Gujarat. We tend to stay away from politics, because politicians tend to misuse our name and they forget us after elections. We will hold a meeting of the Manch in Delhi to decide [on plans for the general election].” Regional rifts in India have been the fly in the ointment for the BJP.

Two worlds collide in Modi’s plans for Varanasi—modernisation vs tradition. An example would be the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor. And another one would be the Alaknanda, the 60-seater luxury vessel that cruises the Ganga at Varanasi. Floated by Nordic Cruise Line, a registered startup, the Alaknanda offers breathtaking cruises at dawn and at dusk. The UP government has backed the startup to the hilt, but the Kewat or Nishad community—traditional boatmen on the Ganga—have been up in arms. Ahead of the recent Pravasi Bharatiya Divas, the boatmen had beached their boats for 10 days. With the high profile event coming up, the government had to handle them with kid gloves. Radhe Shyam, a boatman who lives in Bengali Tola, says, “We have been keepers of the crossing since time immemorial. Do Modi and Yogi think that they can take that away from us?” The employment situation has not improved much in Varanasi, and ventures that eat into traditional jobs are facing a pushback.

A common complaint in Varanasi is echoed by Ram Preet, an autorickshaw driver with roots in Chandauli district: “Kaam hua hai. Magar jitna bhashan diya hai, utna kaam nahi hua hai. (Work has been done, but not in proportion with the speeches given.)” Preet added that he has only two parameters to judge Modi—his home and job. The job front has been so-so, because of rising petrol prices and the horrible traffic. At home, the Ujjwala gas cylinder is a game changer, but it has been a struggle to find money for refills.

Vijay Bahadur Pathak, state BJP general secretary, is confident that the party has not lost ground in Varanasi. “Despite being the prime minister, Modiji worked as a (regular) member of parliament,” he says. “He has changed the ancient city and showed the rest of the MPs how to maintain their constituency.” It is another fact that the average MP does not have the kind of funding or the influence that the prime minister brings to the table.

At the end of the day, the average Kashivasi has not given up on Modi. There is fatigue over propaganda and changing goalposts. A united opposition and internal protests will ensure a good fight. But Mahadev’s city has its hopes pinned on the karyakarta from Vadnagar. They know there is a lot more to be done.

WITH PRATUL SHARMA