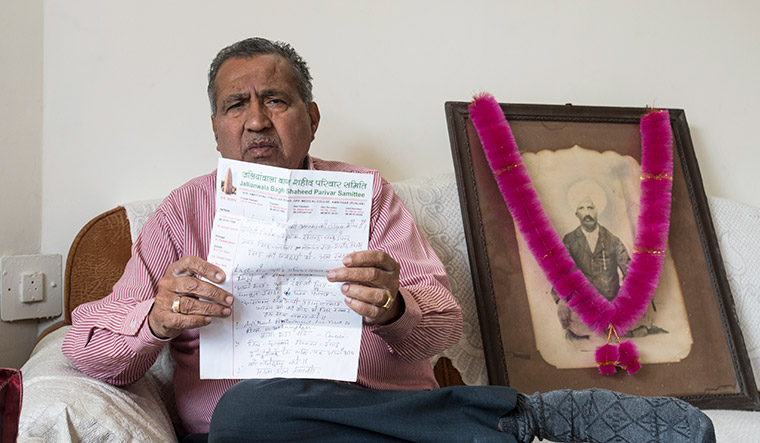

For Satpal Sharma, the story of the death of his grandfather Amin Chand at Jallianwala Bagh is very much a family heirloom. The story is lovingly polished each time it is retold. Like a myth, it gets stronger with each retelling. Krishna Sharma, his wife, has never met her grandfather-in-law. But she breaks down while recounting the story she has heard of. After she married Satpal, this story served as an introduction for her to the new family.

“It was the first place my father-in-law took us to once we got married,” she says. Satpal adds: “People go to mandir after marriage. But for us, Jallianwala Bagh is our mandir. My father took us to the spot where the bodies had lain piled on top of each other, and asked us to pay obeisance.”

Chand was a hakim by profession. His life was devoted to the freedom struggle. His four sons lived in their ancestral home in the village; Chand lived in Amritsar which was then a city caught up in the political churning that followed World War I.

“My father arrived in Amritsar with his younger brother on April 13 [1919],” says Satpal. “The city was at a standstill because of the violence that happened on April 10. My grandfather was very surprised to see them.”

The boys insisted on spending the day in the city with him. So, Chand took them to a famous mithai shop. “Then, he asked them to go home,” says Satpal. “Grandfather had an important meeting to attend at 4pm. My father obediently agreed. But, his brother insisted on accompanying grandfather.”

Reluctantly, Chand, who had a foreboding about the meeting, took his son to the Bagh. “Today, you would never go to a place that is perceived as dangerous. These people insisted on doing just that,” says Sharma, pointing out that the satyagrahis put the struggle above safety.

Satpal’s father had reached Company Bagh in Amritsar when he heard that shots had been fired at Jallianwala Bagh. “My father was only 15. He did not know what to do,” says Satpal. “So, he walked all the way to his village. There he recounted what he had heard. His uncles walked all night to reach the Bagh.”

Bullets had blown Chand to smithereens. He was sitting closer to the stage. The boy had fainted and was later found buried under the heaps of dead. He lived to tell the tale. But, with their father’s death, the boys were on their own. “None of them could study further,” says Krishna.

Across Amritsar, in the narrow lanes behind the milk-white dome of the Harmandir Sahib Gurdwara, Surinder Singh, too, has a story to narrate. He owns a tiny store named Art Heritage. Tracing their lineage from Gian Singh Naqqash—the famed naqqash (fresco) maker of the Golden Temple—Surinder and his brother Satpal Danish sit surrounded by black and white pictures of Amritsar taken on photographic plates, and watercolours of the Golden Temple. Painting runs in their blood.

“I lost my uncle Sundar Singh [in the massacre],” says Surinder, an imposing sardar, sitting behind an ancient desk. “He was only 16.” Sundar’s father survived the shooting, but, he could not save his son.

Sundar had big brown eyes and an easy smile; a picture of him still hangs in the store. At 16, Sundar had already been initiated into the family’s trade of drawing. One of his minutely-detailed pencil sketches survives and hangs in the room—a daily reminder of the loss.

Simran Kaur, his grandniece, says the story is a part of her legacy. “I, obviously, have never met him,” she says. “But, I have heard about the incident and it feels as if I have seen it.” Sundar is a number on the list of the dead, compiled by the British. However, his painting offers a poignant reminder of the man he could have become—observant, sensitive and talented.

Like Simran, Mahesh Behel, too, feels a connection with what happened in 1919. He recounts the story of his grandfather Hari Ram Behel. It is something that has been told to him several times over like a bedtime tale. “It was Baisakhi [festival] and the whole house was in a celebratory mood,” he says. “My aunt was to get married the next month. She was standing at the window when two men called out to her, telling her that her father had been shot,” he says. “The shock of that event never left her. She never recovered.” Ram Behel was brought home bleeding profusely. “My grandmother stood at his bedside weeping,” says Mahesh. “Grandfather was in great pain and was desperate with thirst. She ran to get him water, he took a sip and died.”

But, not everybody got the chance to die at home. After the massacre, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer imposed a curfew in Amritsar. So, the dead remained abandoned in Jallianwala Bagh through the night. However, a woman named Ratan Devi defied the curfew and went in search of her husband. She found her husband’s corpse, but there was nobody to help her carry the body. “I saw other people at the Bagh in search of their relatives. I passed the whole night there. It is impossible for me to describe what I felt. Heaps of dead bodies lay there, some on their backs and some with their faces upturned. A number of them were poor innocent children. I shall never forget the sight,” Devi wrote in her mournful account later.

There were others, too, who could not forget and forgive the British. Udham Singh, who was 20 when the massacre happened, vowed revenge. He completed that 21 years later when he killed Michael O’Dwyer, the Punjab governor during the massacre. But, his great-grandnephew Jagga Singh is oblivious of the legacy he is part of. Jagga is an underpaid construction worker, with mounting debts and no roof over his head. Shivnath Jha, who is working on a book on descendants of Indian martyrs from 1857 to 1947, says the local administration is unaware of the details and the pathetic life that many of these descendants lead. “Zail Singh as president recommended a job for Jeet Singh, grandnephew of Udham Singh,” says Jha. “Parkash Singh Badal as chief minister also gave an assurance of the job. And, still, he has no job.” Jha’s book features bloodlines of 72 martyrs, including three from the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

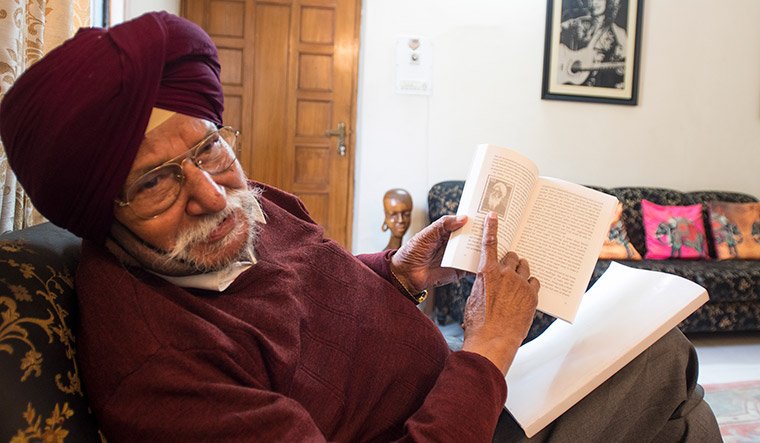

If Udham Singh chose to fight the British with arms, Nanak Singh chose a pen. Nanak, one of the greatest Punjabi writers, was an eyewitness to the horror at Jallianwala Bagh. He had gone with two friends to the Bagh. As the British troops opened fire, Nanak fainted and fell among the corpses. “He came to his senses much later. He had lost an ear,” says Kulwant Suri, Nanak’s son and a publisher.

Nanak was just 22 at that time. After going through the trauma, he proceeded to write Khooni Vaisakhi, a long poem narrating the events in the run-up to the massacre and its aftermath. The poem was banned soon after its publication in May 1920, as it severely criticised the British Raj.

Nanak never saw another copy of that poem. But, almost a decade after his death in 1971, a copy was found in a sack. Suri narrates how he jumped on to an ageing scooter to go track the man who had discovered the poem by accident. The poem has now been translated into English by Nanak’s grandson, Navdeep Suri, and published by HarperCollins India.

Suri says that the book also features an account of Justin Rowlatt, great-grandson of Sir Sydney Rowlatt who drafted the Rowlatt Act. Justin paid an emotional visit to the Bagh. “He wrote how he introduced himself to Sukumar Mukherji, the keeper of the Bagh, believing that the latter would be offended,” says Suri. “He also narrated how he had been overcome with emotion.” This emotional gesture of Justin seems to have brought some sense of peace to Suri. “It is a big thing to have the great-grandson of Rowlatt to write in the book,” he says.

It is coming full circle. Closure?

Maybe not. But a glimpse of much-needed humanity.

Justice above all

Sir Chettur Sankaran Nair, an eminent jurist, was a member of the Viceroy's executive council when the Jallianwala Bagh massacre happened. He resigned from the council in protest and toured Britain to rouse public opinion about the massacre. In his 1922 book, Gandhi and Anarchy, he held Punjab governor Michael O'Dwyer responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh atrocity. Dwyer sued him for libel before the King's division bench in London. The jury decided in favour of Dwyer and fined Nair ₤7,000. Dwyer was ready to forgo the damages if Nair apologised. But, Nair chose not to. Madhavan Palat, Nair's great-grandnephew, says that he paid the fine from the money he had saved for his five daughters.