On May 17, following a gruelling 51-day election campaign, Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised everyone by joining BJP president Amit Shah at a news conference. He said the country had already decided to re-elect the government with a full majority, which was happening after a long time. “After 1975,” Shah whispered to Modi.

A week later, when the votes were counted, Modi returned with a bigger mandate, like Indira Gandhi did in 1971.

The BJP bettered its 2014 tally by 21 seats, aided by gains in the Hindi heartland, West Bengal and Odisha. The party’s vote share was more than 50 per cent in 17 states.

Modi decimated political dynasties and established his image of being a pro-poor leader who could ensure the country’s safety. “I thank people who gave this mandate to this fakir,” he said after winning.

Notably, the pro-Modi sentiment trumped the poll arithmetic of alliances in states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The BJP’s aggressive hindutva message, coupled with nationalism, seemed to have even overcome caste loyalties. The party retained 62 of its 71 seats in Uttar Pradesh, brushing aside the SP-BSP alliance, and the NDA nearly swept Bihar, winning 39 of 40 seats there. The absence of Rashtriya Janata Dal founder Lalu Prasad helped the BJP no end.

Modi addressed 142 rallies, most of them in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Bihar and Odisha. Shah addressed 161, and other senior leaders chipped in to take the number to 1,500 rallies in 51 days.

The Modi wave also washed away the Congress, yet again. The party could only better its 2014 tally by a handful of seats. Ironically, during this campaign, BJP leaders had not used the ‘Congress-mukt Bharat’ slogan. The December defeats in Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh had made them hesitant. Regardless, the BJP retained its Lok Sabha seats in these three states, as well as those in Gujarat, because of the Modi factor. The Congress’s presence, meanwhile, shrunk from 16 states in 2014 to 10 in 2019. Moreover, it could not win any seat in 17 states and Union territories.

In states where the BJP had recently lost, Modi made the elections about him.

“There were many BJP MPs who were afraid to face the people,” a party leader said. “They could not ask for votes themselves as there was anger against them. So they asked votes in Modi’s name to survive.”

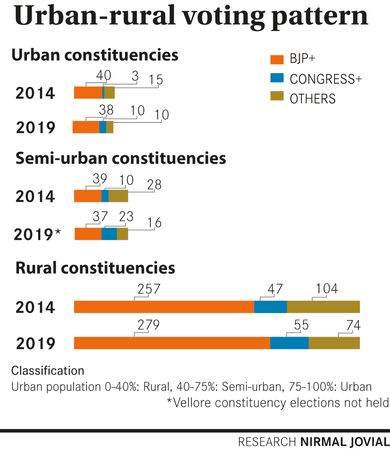

Another similarity between Indira in 1971 and Modi in 2019 was the focus on removing poverty. “They say remove Indira, I say remove poverty,” she had declared then. Modi said a similar line this time, while attacking the opposition. “[They say] Modi hatao. I say we will remove poverty, terrorism and corruption.” His campaign focused on delivery of the Central government’s pro-poor schemes to beneficiaries. “During the 2014 elections, the top of the demographic pyramid, which comprised the BJP’s core voters, was totally saffronised,” said a party strategist. “But the rural poor at the bottom were not. After Modi’s appeal, and Shah’s work, the bottom of the pyramid, which has the maximum number of voters, were converted to saffron, while the top was displeased because of the Goods and Services Tax and demonetisation. Everyone was looking at the top of the pyramid and ignoring the bottom.”

Party leaders were told to appeal to these people, and were asked to talk about the work done by the Modi government in every speech. A little time would also be devoted to attacking the opposition, especially the Congress.

“Only two castes will remain in India. Poor, and those who are doing something to bring the poor out of poverty,” said Modi. “We will work to take people out of poverty and strengthen those who are working for the poor.”

Though Modi was the voice of the pro-poor pitch, it was also Shah’s organisational skill that made it click. The BJP set up 161 call centres with 15,682 employees, who called 24.81 crore beneficiaries of Central schemes. BJP workers contacted them in person, getting their phone numbers, and the call centre workers followed up through phone calls. They were told to remind voters of the gas cylinders, houses and even toilets the Modi government had provided. Separately, the BJP had also held 6.86 lakh programmes to felicitate these beneficiaries.

“Three factors that worked for us were Modi’s leadership, Shah’s strategy to strengthen the booths, and the taking of Modi’s work to the grassroots,” said BJP general secretary Kailash Vijayvargiya.

In his victory speech at the party headquarters in Delhi, Modi said, “Many people make fun of panna pramukhs (page in-charges of a voter list). But these elections have shown their power and effectiveness. I thank them.”

In the 10 months before launching his campaign, Modi had addressed 116 programmes for booth workers. The party had set up committees for 8.6 lakh of 10.5 lakh booths in the country. Shah had also demanded that his party workers organise events at regular intervals to keep the people’s interest alive. Details of each event were digitally recorded. “We have organised at least four programmes in each of the 3,800 assembly seats in the country,” Shah said.

On March 2, for instance, the BJP organised 4,041 bike rallies across the country, in which 28 lakh youth participated. Such events helped create a buzz around the BJP’s strength, as did the campaign to prefix “chowkidar” to one’s name.

“There were 20 lakh tweets and several crore impressions when the chowkidar campaign was launched,” BJP IT cell in-charge Amit Malviya said. The banker-turned political worker was crucial for the party on the social media front. “We have social media units in all states. Apart from all the party cadres connected through social media, and special teams managing these IT cells, we had 12 lakh registered volunteers who would tell people how to use these tools to spread Modi’s message.”

Moreover, there were 2,566 full-time volunteers who promised to give two years of their time to work for the party without pay. They were posted in 120 Lok Sabha seats where the BJP had never won.

The party’s campaign got further impetus following the Balakot air strikes, which established Modi as the deliverer. Nationalism then became key to the campaign. Modi even asked first-time voters to dedicate their votes to the armed forces. Women, too, were targeted, and they voted overwhelmingly for Modi.

The BJP also set up several lakh WhatsApp groups that would steer the conversations towards issues like hindutva, nationalism and the lack of credible opposition to Modi.

The BJP’s campaign committee, headed by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, was responsible for tweaking the campaign messaging as per changing needs. Meetings were held every day, Modi was given feedback, news conferences were organised to counter attacks from rivals and Jaitley wrote blog posts defending the party. This helped ensure that issues raised by the opposition did not stick.

There was, however, one embarrassing moment. Party veteran L.K. Advani, on being denied a ticket, issued a statement on April 4, saying that he had never called opponents “anti-national”. But then Modi and the BJP separately put out the same statement, adding that they were proud that Advani enriched the party. The bomb was defused.

Also read

- Modi returns

- Rahul Gandhi handcuffed by Modi juggernaut

- The Winners…........& the Losers

- Lok Sabha elections 2019: U.P's changing voter profile

- BJP and Shiv Sena: An effective force

- Modiji was most effective

- Modi, BJP have entered Mamata's backyard

- Karnataka: Modi, BJP look to topple coalition government

- B.S.Yeddyurappa: The coalition has flopped

- Kerala: Congress thwarts Modi, BJP wave

Then, when the Congress manifesto promised Rs72,000 to the 20 per cent poorest families under the NYAY scheme, the BJP countered saying that no one from the Nehru-Gandhi family had ever delivered in the past. This also led to more attacks on Nehru, and especially on Rajiv Gandhi, to make sure the Congress could not rely on their goodwill to win votes.

Moreover, social media was abuzz with rumours that the middle class would have to finance NYAY. This campaign, run unofficially, found huge resonance with urban voters.

During the later phases of the elections, the BJP’s campaign turned saffron, with the candidature of Pragya Thakur in Bhopal. The BJP accused the Congress of using “saffron terror” as a ploy to tarnish the image of Hindus. It worked, especially in the Hindi heartland seats.

Another major factor for the BJP’s continued success is the Modi-Shah relationship. There is no competition or communication gap between the two. Shah’s only goal has been to bring Modi back to power. In fact, his obsession with using every available means to achieve this goal saw the BJP’s overseas cell holding activities in 36 countries in the past two months. “We organised 120 programmes to engage with nearly 10 lakh people so that they could influence their families, friends or associates back in India to vote for Modi,” said Vijay Chauthaiwale, BJP’s foreign cell in-charge. “Six hundred of them also came to India to campaign.”

The Sangh also played its part, providing support and feedback to the leaders. It built the nationalist sentiment and kept the hindutva debate alive. The Sangh also postponed its Ram temple campaign so that it would not affect the BJP’s campaign.

“This is the triumph of the national forces,” said Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh general secretary Bhayyaji Joshi. “Many compliments to each and every one who has contributed to this victory of democracy. The spirit of democracy has once again been established for the world to witness.”

The BJP’s stunning victory could mean a cabinet post for Shah—perhaps home or defence—which would assure him a place in the cabinet committee on security. This would kickstart organisational changes as a new BJP president would have to be chosen and perhaps new cabinet members picked.

Several other issues, such as the Ram temple, Article 35A and the education policy, could also come into focus.