I want to try to capture, for readers of THE WEEK, what Gandhi wanted for India. Considering that ‘an Asian century’ and ‘India’s global role’ are on many lips these days, let me begin by recalling the words he offered more than 71 years ago to Asian leaders assembled in Delhi’s Old Fort, or the Purana Qila.

When Gandhi made those remarks in early April 1947, I was present as an eleven-year-old. Even if I understood his words at the time, I quickly forgot them. Yet the scene I glimpsed then, a Purana Qila dais occupied by Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu and a very tall Badshah Khan, remains somewhere in my brain.

In April 1947, let me point out, independence lay four months into the future. Partition had not yet been accepted. In fact, as I would learn much later, Gandhi’s encounter with the gathering of Asian leaders coincided exactly with an ingenious bid by him to avert partition. Between April 1 and April 10 of 1947, Gandhi was urging the new viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, as also the Congress Working Committee to offer the premiership of undivided India to Jinnah.

These urgings took place behind closed doors. Gandhi never spoke publicly about his gambit, whether before or after the Working Committee ‘scotched’ it, to use the phrase Rajaji (Chakravarti Rajagopalachari) entered in his private diary. In their rejection, the Congress leaders were bolstered by effective lobbying against Gandhi’s idea by an alarmed viceroy who, in his own words, was afraid that ‘Mr Gandhi’s scheme may yet go through’ (Transfer of Power 10: 104).

The scheme would have torpedoed the partition plan to which Mountbatten had become attached, and with which, by now, the Working Committee was more than willing to go along.

Gandhi, too, had canvassed his plan, but Nehru, Patel and the other Congress leaders were not willing to be persuaded. Only Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan sided with Gandhi. Conceding his defeat in a letter to Mountbatten, Gandhi left on April 11 for Bihar, to resume his work there for Hindu-Muslim peace. The partition plan went through.

Though they had rejected his advice, Gandhi did not disown the comrades who for 30 years had worked, fought and sacrificed at his side: Nehru, Patel, Rajaji, Maulana Azad, Sarojini Naidu, Rajendra Prasad and company. These colleagues, all younger than him, were going to govern the new India, not Gandhi. He would not undermine them.

Anyhow, here is what Gandhi, leader of India’s movement against imperialism, told the Purana Qila gathering, which Jawaharlal Nehru, member for external affairs in India’s independence-eve interim government, had convened:

All the Asian representatives have come together. Is it in order to wage a war against Europe, against America or against non-Asians? I say most emphatically ‘No’.

Remembering Zoroaster, the Buddha, Moses, Jesus and Muhammad, Gandhi called them ‘Asia’s wise men’, adding, ‘I do not know of a single person in the world to match these men of Asia.’ Gandhi went on to say,

I [am] an inheritor of the message of love that these great unconquerable teachers left for us.”

“I want you to go away with the thought that Asia has to conquer the West through love and truth.

In this age of democracy, in this age of awakening of the poorest of the poor, you can redeliver this message with the greatest emphasis.

“You will complete the conquest of the West not through vengeance because you have been exploited, but with real understanding…. This conquest will be loved by the West itself (Collected Works 87: 182-83, 190-93).”

‘Hate not,’ Gandhi was saying to Asians who resented the European colonisation that was approaching its end. Vengeance was folly. But ‘conquest’ of another kind was fair. Asians could ‘conquer’ the West with love and truth.

Frankness: In April 1947, compassion and truth were needed within India as well, including in Bihar, to which Gandhi returned. In March he had gone there from Noakhali, an eastern district in what then was India’s Bengal province. In four months, East Bengal would become East Pakistan. In 24 years, it would become Bangladesh.

In 1947 and the previous year, Gandhi’s mission was to impart courage to victims (Hindus in Noakhali, Muslims in Bihar), and to confront aggressors with truth about ugly deeds recently enacted (by Hindus in Bihar, Muslims in Noakhali).

Meeting him in Kolkata in the summer of 1947, an African-American scholar visiting India, William Stuart Nelson, asked Gandhi why killings had occurred despite 30 years of teaching nonviolence. Gandhi’s answer, in effect, was that while many Indians had embraced his teaching of ‘Fear not’, many had rejected his teaching of ‘Hate not.’

At first, the white man was hated. Then hate switched to Indians of the ‘other’ religion. Following the acceptance of partition, when hating and killing spread to Punjab and multiplied there to horrific levels, Gandhi gave similar answers to Indians who asked why seemingly peace-loving Indians had become unbelievably cruel.

Many in the world were greeting India’s independence as a triumph of nonviolence. However, Gandhi was aware of India’s hospitality to violence. In a prayer-meeting talk on June 16, 1947, he admitted that India had accepted his nonviolent satyagraha not because violence was a horror, but because satyagraha seemed more effective than violence against the empire. Said Gandhi:

“No one at the time (during the battles for Swaraj) showed us how to make an atom bomb. Had we known how to make it, we would have considered annihilating the English with it (Collected Works, 88: 163).”

In their anger (Gandhi warned), Indians—the ‘we’ with whom he always identified himself, even when they went against him—might even have contemplated limitless violence, with dissenters like Gandhi protesting with their lives.

Reconciliation: Though he was unable to avert either partition or the carnage that accompanied it, Gandhi’s efforts in the last two years of his life—in Noakhali, Bihar, Calcutta and Delhi—limited the violence. More than that, the efforts produced a scaffolding for reconstruction.

His fasts for harmony (Calcutta, September 1947, and Delhi, January 1948) altered the psychological climate. His fearless walks in Muslim-dominated Noakhali and blunt words in Hindu-dominated Bihar taught India that the real fight was between inhumanity and decency, not between Hindu and Muslim.

Over the previous decades, right from 1917, Gandhi had put together audacious Hindu-Muslim alliances between political parties. He had also generated fervour in the masses for united resistance against the empire. But his was not the only voice reverberating across the subcontinent. Opposing cries, anti-Muslim from one direction, anti-Hindu from another, were also being raised.

These negative cries were passionate. At times they were successful. Alliances were therefore made and unmade. Fervour rose and fell. Moreover, political alliances were seldom translated into ground-level partnership in India’s villages and towns.

In the last two years of his life, Gandhi reverted to becoming the field worker he was 50 years earlier, soon after arriving in South Africa as a 23-year-old. From 1946 onwards, Gandhi left most aspects of summit-level politics to Nehru, Patel and company and became a pilgrim for reconciliation on the ground. Taking with him a small band of fellow-pilgrims, he worked in East Bengal, Bihar, Kolkata and Delhi.

He did something else. In November 1947, he successfully insisted that the Congress Working Committee and the All India Congress Committee reiterate the freedom movement’s commitment to an India of equal rights to ALL. Nehru and Patel backed him, and free India was launched as a nation where in law at least there was equality.

This pledge was soon enshrined in the Constitution, in creating which, as everyone knows, a central role was played by Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar. Although the Congress and Ambedkar had been involved in bitter disputes from 1931 to 1946, the coming of independence saw a change. Gandhi, Nehru and Patel invited Ambedkar to steer Constitution-making, and Ambedkar showed his love for India by accepting the invitation.

In India’s angry climate of 1946 and 1947, when Pakistan was secured in an atmosphere of mutual hatred and violence, and strident calls were raised to make Pakistan an Islamic state, there was no certainty that India would choose to be a secular state with equal rights for all. A Hindu state in India seemed natural to many.

Though immersed in seeking reconciliation on the ground, Gandhi saw to it that toxicity did not influence India’s leaders, who rejected a Hindu state. In some ways, ensuring equal rights at free India’s birth was a feat more impressive than attaining independence.

That the new India was going to be for all Indians was also indicated by the composition of independent India’s first cabinet, chosen by Nehru and Patel with inputs from Gandhi.

Its 14 members included two Muslims (Maulana Azad and Rafi Ahmed Kidwai), two Christians (John Matthai and Rajkumari Amrit Kaur), two Sikhs (Baldev Singh and Amrit Kaur), a Parsi (C.H. Bhabha), two dalits (Dr Ambedkar and Babu Jagjivan Ram), one Hindu Mahasabha member (Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee), and one former empire loyalist (R.K. Shanmukham Chetty). Nehru, Patel, Rajendra Prasad and Pune’s N.V. Gadgil completed the team.

Trust on the ground: Let me return, however, to the question of field work for peace. Contrasting trust between communities, for which Gandhi strove, with bids by a government to win the trust of an individual or a community, poet-academic Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee observes that “trust, in the Gandhian sense, is an endearing and enduring state of confidence between people and communities (thewire.in).”

Bhattacharjee argues that for Muslims and Hindus to trust each other is more important in India than for either community to trust a government. Mutual trust among a people builds democracy. Distrusting your neighbour while trusting the government is the road to dictatorship.

More than 53 years after Gandhi’s trek there, I twice visited Noakhali, in April and November 2000, and spoke to its Muslim and Hindu villagers. They did not know that I was Gandhi’s grandson. The old among them were in their teens when, during the 1946-47 winter, they had seen Gandhi. Others had heard of Gandhi’s doings on their soil from their elders. Interestingly, many residents spoke of these doings as if they were describing recent happenings.

Thus, when I encountered Sirajul Islam Majumdar of village Kamalpur, who was in his late fifties and the son (he told me) of Dr Khaleelur Rahman Majumdar, he said, “My father told us about Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram, Ishwar Allah Tere Naam.” The lines were sung to me by Sirajul, not recited. “My grandfather protected Hindus on his roof,” he added.

Recorded in Mohandas (my Gandhi biography), these interviews in Noakhali with Sirajul and others indicated that within months of traumatising events, a degree of trust between Muslims and Hindus had been restored by Gandhi and his small team.

There may be a major lesson here for India and for every nation where walls or distances have grown between communities. Persons who empathise, listen and speak frankly may restore relationships.

Right to dissent: From an early age, Gandhi was clear that India’s independence would mean little if it did not also mean the independence of every Indian. Written in 1909, his Hind Swaraj underlined this. More than 30 years later, while launching Quit India in Mumbai on August 7, 1942, Gandhi told the Indian people:

“I have read a good deal about the French revolution. Carlyle’s works I read while in jail. I have great admiration for the French people. Pandit Jawaharlal has told me all about the Russian revolution. But I hold that though theirs was a fight for the people, it was not a fight for real democracy, which I envisaged.”

“My democracy means every man is his own master (CW 76: 380-81).”

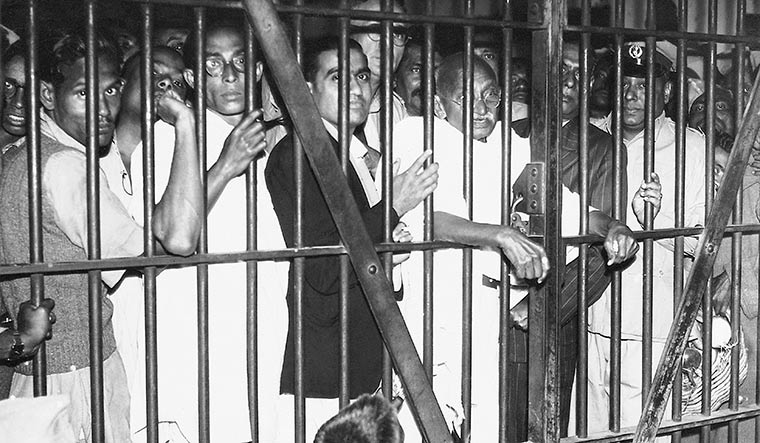

Quit India shook the empire, but it also brought imprisonment and death to fighters for liberty. Among those who died in detention was Gandhi’s wife, Kasturba. In the summer of 1945, three years after Quit India, most of the jailed were released, and freedom was near.

In the following year (February 1946), a short-lived yet significant mutiny by Indian ratings in ships of the Royal Indian Navy created considerable animation in Mumbai, Karachi and Vizag. Although no Indian officer joined the mutiny, thousands of workers in Mumbai struck work in sympathy. Excited mutiny supporters demanded participation by everyone they came across in the streets of Bombay, forcing many to shout the popular cry, ‘Jai Hind.’

Responding from Pune, where he was at the time, Gandhi said: “Inasmuch as a single person is compelled to shout “Jai Hind”, or any popular slogan, a nail is driven into the coffin of Swaraj in terms of the dumb millions of India (CW 83: 171).”

In Gandhi’s Swaraj, the weakest Indian had the right to dissent. In his view, bullies were Swaraj’s annihilators.

Fighting and praying: In the heated climate of 1946-48, Gandhi’s daily prayer-meetings, which were open to everyone and where verses from different faiths were recited, became essential classes in democracy and tolerance. Occasionally, in Delhi, there were objections to the reading of lines from the Qur’an. At times in Noakhali, Muslims walked out when lines about Rama were chanted.

Most of the time, however, Hindus and Muslims joined these multi-faith events, which helped reverse the tide of polarisation. A four-word sentence, Ishwar Allah Tere Naam, and two paired phrases, Ram-Rahim and Krishna-Karim, became well-known sounds that served to heal a wounded nation.

I think it is impossible to separate Gandhi, the public campaigner, from the inner Mohandas. We cannot separate Gandhi, the leader of millions, from the personal Gandhi who prayed, often from a position of helplessness, for strength and wisdom from God. Those who study his life will inescapably confront both Gandhis.

Shortly after Gandhi’s 1924 arrest (which was one of many in his lifetime), his son Devadas and the Congress leader from the south, Rajaji, visited him in Pune’s Yeravada prison. Learning that Gandhi was sleeping on a flimsy blanket in a solitary cell, was locked in at night, using some of his books as a pillow, and was being denied newspapers and periodicals, Rajaji wrote in Young India (April 6, 1922) that India’s white rulers were unaware of their “privilege of being custodians of a man greater than the Kaiser, greater than Napoleon... greater than the biggest prisoners of war”.

Two years later, a released Gandhi referred to the same historical personalities but in a different vein: “Man is nothing. Napoleon planned much and found himself a prisoner in St Helena. The mighty Kaiser aimed at the crown of Europe and is reduced to the status of a private gentleman. God had so willed it. Let us contemplate such examples and be humble (Young India, 9 Oct. 1924).”

Whether planning a national campaign, or writing an article for his journal, or spinning his charkha, or fasting, or speaking at his prayer-meeting, Gandhi would pray silently or openly for God’s strength.

And for wisdom from God. The second line of the powerful Ishwar Allah Tere Naam couplet says, Sabko Sanmati De Bhagawan. It is a prayer for ‘discernment’ or for ‘good or constructive thoughts’ in all.

The fighter who mobilised Indians of all backgrounds for great struggles, saying he himself was always ready for anything, was also one praying all the time for strength and wisdom.

A distinct ahimsa: For long reduced to rules of diet, India’s ancient concept, ahimsa, was given potent new meanings by Gandhi. After it passed through his hands, ahimsa became a weapon for struggle as also a guide for interpersonal relations.

During his life-long efforts to put across the folly of violence, Gandhi frequently used extreme language. Taken out of context, Gandhi’s sweeping words about ahimsa’s power could even suggest that he wanted independent India to have no army or police.

That was certainly not the case. As is well-known, Gandhi did not object to the dispatch of Indian soldiers to Kashmir in October 1947, and there is no record of any private or public suggestion from him for disbanding India’s military forces.

At his prayer-meeting on November 24, 1947, Gandhi gave his opinion on when and how a kirpan, the traditional Sikh sword, may be used:

Also read

- PM Modi pays homage to Mahatma Gandhi at Rajghat

- Rediscovering peace at Gandhi's Sevagram Ashram

- 'Tatva' of Gandhi's philosophy remains same, 'tantra' will differ

- Mahatma Gandhi's ideas for the world

- Many faces of Gandhi

- The unknown Gandhi: The extraordinary journey from Mohandas to Mahatma

- Canonising Gandhi made him a myth more than a man: Mark Tully

- Gandhi was not a caste abolitionist: Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd

- Gandhian philosophy needs to be practised: Tushar Gandhi

- Gandhi, Savarkar two irreconcilable poles in Indian history

“A sacred thing has to be used on sacred and lawful occasions. A kirpan is undoubtedly a symbol of strength, which adorns the possessor only if he exercises amazing restraint over himself and uses it against enormous odds… (CW 90: 98).”

Three weeks earlier, referring to Afridis from Pakistan’s tribal areas who had raided Kashmir with the backing of Pakistan’s government, Gandhi had similarly said that he would not ask the Afridis to give up their arms. They could keep the arms, but only “in order to protect the indigent, the women and the children’ (CW 89: 460).”

As Gandhi saw it, weapons were of value only when used by persons of courage and restraint to protect innocent life. They were a menace when used to threaten the vulnerable.

Will Gandhi be shocked today? It may be asked whether Gandhi’s spirit, wherever it resides, is shocked, 71 years after his death, at praise from some quarters for his assassination. In 1915, more than a hundred years ago that is, and only some months after he had returned for good from South Africa, Gandhi was asked by a young man from Gujarat, Indulal Yagnik (who would become an often-critical ally), whether he expected a following for civil disobedience in India.

Replied Gandhi: “I am not very much worried about securing a large following. That will come in due course. But I do anticipate that a time may come when my large following may throw me overboard on account of my strict adhesion to my principles—and it may be that I shall almost be turned out on the streets and have to beg for a piece of bread from door to door (Yagnik, Gandhi As I Knew Him, Danish Mahal, New Delhi, 1943, pp. 9-10).”