The Dalai Lama, now shrunken and frail, sometimes needs his followers’ support to move around. Yet, he remains a pillar of support to millions worldwide, many of whom cross mountains and oceans to meet him and seek his healing touch.

The spiritual leader lives in Thekchen Choeling in the small town of Mcleodganj in Dharamshala, welcoming the diseased, the sinned and the enlightened together with open arms.

The scene was no different when we met him on June 28. His followers had been waiting for him since daybreak carrying the khata (a Tibetan scarf offered to a dear one), hoping for a glimpse of him.

At 9am, as I stood outside the temple, soaking in the positivity of the moment, the figure in a maroon robe walked towards his audience. Then he stopped and turned to me. “Touch my head,” he said. While I wondered if I should, his Indian security officials shifted in discomfort. “I need a healing touch,” he said, encouraging me and evoking a bout of compassion not just in me, but also in the large gathering. I obliged.

He then walked towards the waiting audience and spoke in Tibetan. He pointed to his forehead and showed them an infection. It was perhaps a reaction to the antibiotics he took after a recent hospitalisation (a rare occurrence). He then asked them to heal him. The eyes that had so far been stuck on his footsteps rose to his face and started welling up. Could the Dalai Lama, who transcends the miseries that inflict mortal souls, suffer? A young woman broke down and ran towards him. The Dalai Lama gave a radiant smile—he had reminded his followers that he, too, was human.

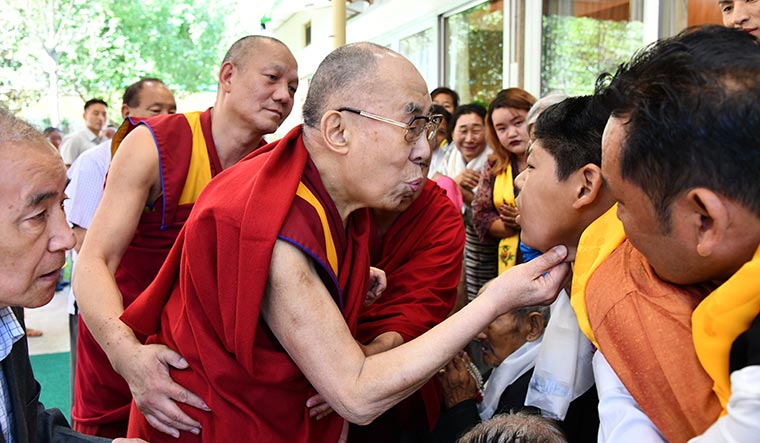

As he sat on his chair, people came to him one by one. They tightly gripped his hand. Even his security men shed a tear as the Dalai Lama touched a speechless boy on his neck and blew on his forehead, making him smile. The boy then took away his wheelchair-bound grandmother, knowing he had found hope that day.

Born Lhamo Thondup in Tibet in 1935, and recognised at age two as the reincarnation of 13 spiritual ancestors, the Dalai Lama has been living in India for 60 years and will turn 84 on July 6. Questions of his mortality and reincarnation are being discussed not only in Mcleodganj, but among Tibetans all over the world and in political and diplomatic offices in Delhi, Beijing, Washington and elsewhere. Enthroned before he turned four, the Dalai Lama’s stature in India is nothing less than that of the Buddha reincarnated. He, however, would not agree. He says the Buddha did not reincarnate, and neither did any of the spiritual gurus of Nalanda (see interview).

The Dalai Lama’s routine is now fixed. He wakes up at 3.30am, performs prayers, takes a shower in warm water treated with Tibetan herbs, meditates, and meets his private guests from 9am till 11.30am. He eats frugally, but does not like to be disturbed while eating. After lunch (he likes rice and dal), he reads holy texts, meditates and sometimes watches television for news. He takes a light snack, mostly tea and a biscuit, at 4.30pm. He winds up the day by sunset, and sleeps for nine hours. “The best form of rest for him,” quipped an aide.

The Dalai Lama says that while he may have got his physical form from Tibet, his spiritual consciousness was Indian. “I consider myself a son of India,” he told THE WEEK. “My way of thinking has been shaped by the works of the masters of the historical Nalanda university, which I have studied since childhood.”

He also talks about India to those seeking spiritual solace, such as Simran Mittal, a student from Himachal Pradesh, who broke down when she asked him what the purpose of her life was. The Dalai Lama held both her hands and said: “As a young Indian, you should feel proud that India is the only nation that can combine modern education that brings physical comfort, and ancient knowledge on how to tackle destructive emotions and keep peace of mind. It is the only country that talks of ahimsa (nonviolence) and karuna (compassion) in the 21st century. India can make significant contributions to world peace through inner peace. I sometimes feel I am more Indian than western-educated Indians.”

Then he laughed. The Dalai Lama laughs a lot and giggles like a child. His eyes twinkle all the time. But when he speaks, he does not break eye contact till he has completed what he is saying.

Indeed, ahimsa is the greatest article of his faith. In 1950, after China’s invasion of Tibet, the Dalai Lama was called upon to assume full political power. In 1959, after the brutal suppression of the Tibetan national uprising in Lhasa by Chinese troops, the Dalai Lama sensed a threat to his life and, at the age of 24, fled to India with a retinue of soldiers and cabinet ministers. The one lakh Tibetan refugees who followed him are today expressing gratitude to India for showing compassion and large-heartedness.

As we moved on from the temple, we found the Tibetan Children’s Village tucked in a corner in Dharamshala. We saw children in uniform drinking water from a tap installed in a crevice in a green hill. They smiled and waved at us. Atop the hill was the dormitory where neatly kept bunk beds, and the care of a foster mother provide them a home away from home. “One of the critical needs of that time was to provide care for the many children who had been orphaned or separated from their families while fleeing Tibet,” said Tsultrim Dorjee, director of TCV in Dharamshala. “The first batch arrived from the road-construction camps in Jammu; they were ill and malnourished. His Holiness proposed that a centre for destitute children be established and, with the help of the government, the Tibetan Children’s Village was born. Today, it is a thriving educational community with several branches in India, extending from Ladakh in the north to Bylakuppe in the south. It has more than 16,000 children under its care.”

Not only children, but women from the trans-Himalayan region, too, have made India their home. Nangsa Chodon, who takes care of the Dolma Ling Nunnery in Sidhbari and is the director of the Tibetan Nuns Project, recalled with pain the protests against Chinese rule by monks and nuns in Tibet in 1987. The situation was so heart-wrenching that they started fleeing to India, which had by then helped the Dalai Lama settle and had given land to the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), of which he was the temporal and spiritual head. After some years, he transferred the temporal power to a prime minister elected by the Tibetan community in exile.

Nangsa, who worked in the Tibetan government as education secretary before retirement, said that while the monks who came into India settled in monasteries, the nuns had no place to go. “His Holiness sensed this and told his sister, who was president of the Tibetan Women’s Association, to do something,” said Nangsa. “They soon rented a small office and started enrolling all the nuns coming into exile. Today, Dolma Ling Nunnery has around 250 nuns, and has become a full-fledged educational institution teaching English, maths and science, and helping the nuns obtain doctorates in philosophy and so on.”

Today, not only is the institution of the Dalai Lama deeply entrenched in Mcleodganj and Dharamshala, there is integration of the Tibetan people into Indian culture and ethos.

“His approach towards Buddhism is very rational, which is relevant in the 21st century,” Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu told THE WEEK. “He is an embodiment of compassion and we revere him as the living Buddha. His teachings have shaped me as a person.”

The Nalanda masters would be happy.

But, where is the Tibetan freedom struggle today? “When I was a young child, my grandmother used to tell me stories of snow mountains and yaks and I was thrilled,” said Tenzin Tsundue, poet and activist who is at the forefront of the Tibetan freedom struggle today. “Then she told me I came from that land and at that time I did not believe her. All I saw then was brick and mortar, and the sweat and heat of the refugee camp in Karnataka.”

Tsundue, 45, lives in a dilapidated old British bungalow in Dharamshala, which has become the nerve centre of the freedom struggle. It is from here that the Tibetans across the world join him for discussions, seminars and protests. Tsundue’s parents were construction workers in Mandi in Himachal Pradesh, like most Tibetans who came as refugees to India. “We will not give up,” said Tsundue, who has been to many Indian jails, as well as two Chinese ones in Tibet. “As long as we do not give up, there is always hope. No matter how big or powerful your enemy is. I am inspired by Bhagat Singh and [Mahatma] Gandhiji. If we throw out the Chinese by way of violence and instal the Tibetan flag, then we have stopped being Tibetan.”

Tsundue reminded us that Tibetans were “warriors” who killed people, occupied countries and extended their empire right into the heart of China. “China’s old capital Changán, which is now called Xián, used to be an occupied country under the Tibetan emperor. At the height of the Tibetan empire building, they gave freedom to China and the Chinese said they were happy in China and the Tibetans were happy in Tibet. By then Buddhism had come to Tibet. We started understanding that victory could only happen if you gain victory over your anger, hatred and greed. That made us Tibetan. The danger posed by China is because it is bringing double the population of Tibet, twelve million Chinese, in the place where there are only six million Tibetans. So there is a danger of physically decimating us just as Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi. The spirit of Gandhi lives even today, but the person died and could not continue the work. So we can always praise the spirit of the Tibetan people, but what if you are physically killed? That is the danger we are fighting.”

And that is why Karma Gelek Yuthok, the minister of the department of religion and culture under the CTA, is a worried man. “Although Tibet is now with China, they fail to think that Tibet is theirs,” he told THE WEEK. “Since 2008, the Chinese government has stopped the inflow of people from Tibet to China. What is happening now in Tibetan monastic centres is impossible to believe. They are removing the photos of the traditional masters and putting up pictures of the Chinese leaders and those coming there to worship are forced to worship those pictures. These monastic centres are becoming just like military camps. There was a tradition of schoolchildren spending some time in the monasteries. Now they have restricted even that. They seem to be determined to finish Tibetan Buddhism, which is very sad.”

But there is a ray of hope. The Buddhism preached by the Dalai Lama is becoming a way of life for many people across continents. While the Tibetan population may be on a decline in schools and monasteries, about 60 per cent of the students in several monastic institutions across the country are Indians from the border region—from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh—and others from the trans-Himalayan region. They are inheriting the Tibetan culture.”

Also read

- Dalai Lama's office reacts to China's statement; hits out at Beijing's propaganda machine

- US lawmakers Michael McCaul, Nancy Pelosi scheduled to visit India next week to meet Dalai Lama

- OPINION: Buddhism as soft power and the gift of the Dalai Lama’s presence

- OPINION: Campaign against Dalai Lama has deeply hurt Tibetans' sentiments

- 'Often teases people': Dalai Lama issues apology to boy, his family after kissing video goes viral

Another ray of hope comes from the Indian government. The Dalai Lama described the India-Tibet relationship as one of a guru and a chela (follower), and it might be time the guru does something for the chela once again. At a time when Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his team of security czars led by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval are firming up the Tibet policy for the second term of the BJP government, CTA president Lobsang Sangay, in an interview with THE WEEK, made an appeal to the Indian government to make Tibet a core issue.

The Dalai Lama also reminded India why it could trust Tibet. “Tibetan people have showed India that they have kept its tradition safe, especially at the time when British rulers neglected it. So, we have showed India that we are not only the chela, but the most trusted and reliable chela.”

China, on the other hand, continues to distrust him. An official who was part of a delegation from Beijing to New Delhi last week told THE WEEK that the Dalai Lama cannot hide his agenda as a separatist. He also insisted that his reincarnation would be cleared by the Chinese government. He added that the Dalai Lama had expressed his desire to go back to his homeland several times, but it would have to be done through negotiations between the Chinese government and the Dalai Lama. “There have been many rounds. But he should give up separatist activities first,” he said. The Dalai Lama, for his part, said that Chinese communism would not last long.

What began as an independence struggle has evolved into a middle-way approach for stability and coexistence between the people of Tibet and China. And the Dalai Lama is firm on prioritising restoration of “real freedom” through ahimsa and karuna above everything else, even over the human desire to return to his homeland. “Let them (China) say I am a separatist,” he said. “I will be happy to live in India for the rest of my life.”