December 29, 1971, 5am

It is the second last day of the first shooting schedule of my first film, Sonal. We are in Bombay, at Papa’s official residence on Little Gibbs Road. As I rush out, I bump into him, as he is off to catch a flight to Trivandrum (en route to Thumba). I give him a kiss, and say, “See you tomorrow night.” We have a date—he, Amma and I—to be together and dance at the Ahmedabad Gymkhana on New Year’s Eve. Amma is in Bombay, too, and we are all slated to fly to Ahmedabad on the morning of the 31st. I suddenly remember that he had his annual medical check up the previous day. “What did the doctors say? Is the blood pressure under control?” I ask. “Don’t fuss Malli. I am fine.” He sticks his tongue out at me. I roll my eyes, give him another hug.

December 30, 1971, 11am

We are in the middle of a shoot in a studio in Andheri. At the end of a take, an assistant comes and whispers in the ear of my director, Prabhat Mukerjee. He leaves the set. In a few moments, he is back and walks up to me. “Come, Mallika. I am taking you home. Amma is unwell,” he says. Amma, unwell? I search his face. He averts his eyes. My heart sinks. We take a taxi. He looks out of the window and periodically says, “Don’t worry.” My world is collapsing inside me. Is she dead? Has there been an accident?

We enter the compound. It is filled with cars. The lobby is full of people in white. People avoid my eyes but make way for me. Some look at me with tears in their eyes. The elevator ride to the top floor is interminable. I am shaking. I want to scream. The door is open. Papa’s secretary is at the door and says, “Come to Amma.” I look at him, puzzled.

Amma sits on their bed, her back turned to the door, her head in her hands. A close friend holds her. She looks distraught, not ill. I walk slowly up to her. She looks up. Her face is streaked with tears. “Papa has gone.” I can not fathom it. Gone, where? “Darling, papa has gone,” she repeats. My mind races. Accident. It has to be. He was fine. I checked only yesterday. “Accident?” I ask, in a whisper. She shakes her head. “No, in his sleep.” My world crashes.

***

There are three events that stand out in my mind from the 17 years I could spend with Papa. Three events that have defined me and who I am.

It is my first day in a Montessori school. We are seated in a circle drawing a face. I draw the ears in the wrong place and the boy next to me says, laughingly, “What an ass you are.” I am very upset and tell Papa, crying that I will not go back to that school. Papa laughingly picks me up and puts me in his lap. “Malli, who are you?” he asks. “I am a girl,” I respond through sobs. He laughs and says, “Malli, you know that you are a girl. He does not know the difference between a girl and an ass. You should feel sorry for him.” Learning: Do not let stupid comments or criticism upset you. They come from ignorance or malice.

Also read

- Chandrayaan-2: Hope dims for Vikram lander as lunar day ends

- Moon mission would be successful on 'Ekadashi' day, claims Hindutva leader

- Chinese netizens praise Chandrayaan-2, ask scientists not to lose hope

- ISRO locates Vikram lander intact, but tilted on lunar surface

- Location of lander proves orbiter functioning well: Expert

- Chandrayaan-2: Vikram traced, but re-establishing communication 'less probable'

I am 12. My school has many new students. Gujarati kids are being sent to boarding schools in India from Uganda and Kenya, as Asians flee Idi Amin. Two boys in my class, several years older, have a fight about whose girlfriend I am. One knifes the other; the injured boy has to go to the hospital to get stitches. My aunt, the principal, calls Papa in the false belief that there can be no smoke without fire.

Papa is amused that the boyfriend business has started so early. I am furious at the injustice of it all. “It is not fair to blame me,” I say. “I don’t even know them well. I had nothing to do with this.” Papa sits me down that evening. “Malli, I didn’t think this discussion would happen this early, but we might as well have it,” he says. “In society, there are two kinds of people. There are those that unquestioningly follow what others do, what society does. And then there are those who question things, who search for their own truth, make their own rules, and do what they think is right. Amma and I are like that. You must decide what you want to be. If you decide to follow your own truth and stand up against society and people, they will always try and abuse you and hurl stones at you. Each of us must choose.” I went away and it gnaws at me for a few days. “Papa, I need to live with what I believe is true,” I tell him. Learning: Standing up for what we believe is true, taking on society for what we think is wrong or unjust, is stormy and thorny. Do it only if you are willing to be stoned.

I am 16. Papa has been away. I am running down the stairs in our home when he runs up. We meet at the landing. I see that he is deeply upset. I ask why. “They offered me a bribe to get India to sign an agreement with them. What do they think I am?” he asks, pain, hurt and disbelief in his eyes. Learning: No matter what your own ethics are, people will think you have a price, that nothing is beyond being bought. They are wrong.

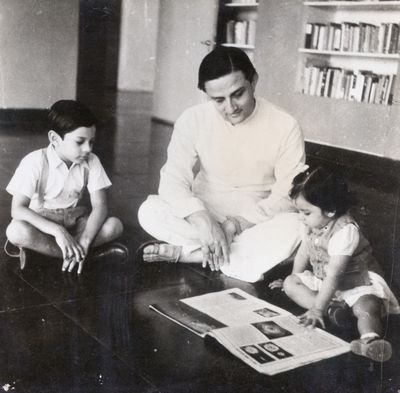

I miss him. I believe that a lot could have been different for this nation had he lived. But he lives in his institutions and the people he inspired, and continues to inspire; and in us, his children, and in our endeavours and dreams.

—Mallika Sarabhai is a classical dancer and actor, and daughter of Vikram Sarabhai.