Mohammad Sanaullah is free, for now. But his mind is not without fear, and his head is not held high.

The 51-year-old had been a fearless and proud soldier for 30 years. He had joined the Army’s Corps of Electronic and Mechanical Engineers in 1987, and served with distinction in Jammu and Kashmir, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur. He was attached to the Rashtriya Rifles for six years, before he retired in 2017 with the rank of honorary lieutenant.

Sanaullah’s world came crashing down on May 28 this year, when the foreigners’ tribunal declared him a Bangladeshi and sent him to a detention camp in Goalpara district. The welcome at the camp was humiliating. He was lodged in a mosquito-infested room with 55 others, and was tortured, starved and forced to relieve himself openly.

News of his detention created a huge uproar. The police said it was only following rules and guidelines, and that a case against Sanaullah had been registered at the Boko police station in Kamrup district in 2008. The case was transferred to the Guwahati bench of the foreigners’ tribunal two years later, and the tribunal’s verdict was based on a report submitted by the border branch of the Assam Police.

The public outcry saw Sanaullah case being taken up by the Gauhati High Court. Supreme Court lawyer Indira Jaising flew to Guwahati to help his team of lawyers. Led by advocate Syed Burhanur Rahman, the lawyers worked for free to secure him bail.

“The situation of most people who have been accused of being Bangladeshis is pathetic,” said Rahman. “They are very poor. How could we charge them?”

Sanaullah was granted bail on condition that he remain in Guwahati. The ordeal has so upset him that he now fears going out and meeting strangers. “Only 25 per cent of my objective has been met; 75 per cent is still pending,” he said when THE WEEK met him in Guwahati. “I have no reason to celebrate. In the eyes of the law, I am a foreigner. The onus is on me to prove that I am an Indian. It is a pity that I have to prove this at this stage.”

The police had earlier told journalists that Sanaullah’s arrest was a “mistake”, but his lawyers say it would not help his cause. “The police did not say so in court,” said Rahman. “In fact, they stood by their report. What the officers say outside is immaterial, unless they say the same in court.”

Senior police officers told THE WEEK that the case against Sanaullah will not be withdrawn. Though he lives in an apartment in Guwahati, his documents show he is a resident of Kalahikash village near Boko, a town in Assam’s Kamrup district. “According to his documents, his sister was born seven years after her mother’s death. False documents were produced, and the police had no choice but to suspect him. The tribunal upheld [the suspicion],” said an officer.

Interestingly, when he was declared as a foreigner, Sanaullah was employed as a sub-inspector in the Assam Police Border Organisation, which is tasked with detecting and detaining suspected foreigners in the state. He was discharged from his duties a day after the tribunal declared him a non-citizen.

“He was a very able and efficient officer,” Bhaskar Jyoti Mahanta, special director-general of police (border), told THE WEEK. “In fact, he himself referred many cases to the foreigners’ tribunal. He did his work honestly. Now, so far his case is concerned, we cannot interfere because it is a matter between him and the tribunal.”

Sanaullah will be back in the detention camp if the tribunal’s verdict is upheld by the High Court and the Supreme Court. According to the tribunal, he had entered Assam by crossing the porous India-Bangladesh border some time after March 25, 1971—the cutoff date for citizenship claims as per the 1985 Assam Accord.

On May 28 this year, an unsuspecting Sanaullah was summoned to the office of the superintendent of the border police at Amingaon in Kamrup. He was interrogated and taken into custody late in the evening.

Insiders say officers of the department were unhappy with the way his case was handled. Sanaullah apparently reacted angrily when he was asked to prove his citizenship, and said he would contest the charges against him in court. That resulted in his immediate transfer to the detention camp.

When THE WEEK met him at his relative’s house in Guwahati, Sanaullah appeared shaken and hurt. His lawyers and well-wishers in the police had asked him not to talk to journalists. “I hang my head in shame,” he said. “Please excuse me; I cannot talk. I cannot reconcile myself to the charge that I was a Bangladeshi who worked in the Indian Army.”

Sanaullah said his wife, Sanima Begum, also lives in shame. “She goes out and often stays in our village,” he said. “No one hurls abuses at us, but many look at us suspiciously.”

Sanaullah has two daughters and a son. Sahanaj, the elder daughter, is married and Helmina is a nursing student. Son Sahid is a physiotherapist in Guwahati. According to the police, the names of Sanaullah’s children vary across documents, and none figured in the draft of the National Register of Citizens published last year. Sanima Begum made the list since her father was a documented citizen, unlike Sanaullah’s father. But the children were excluded because they had used Sanaullah’s legacy data—a set of documents that proves that one’s ancestors were residents of Assam before 1971.

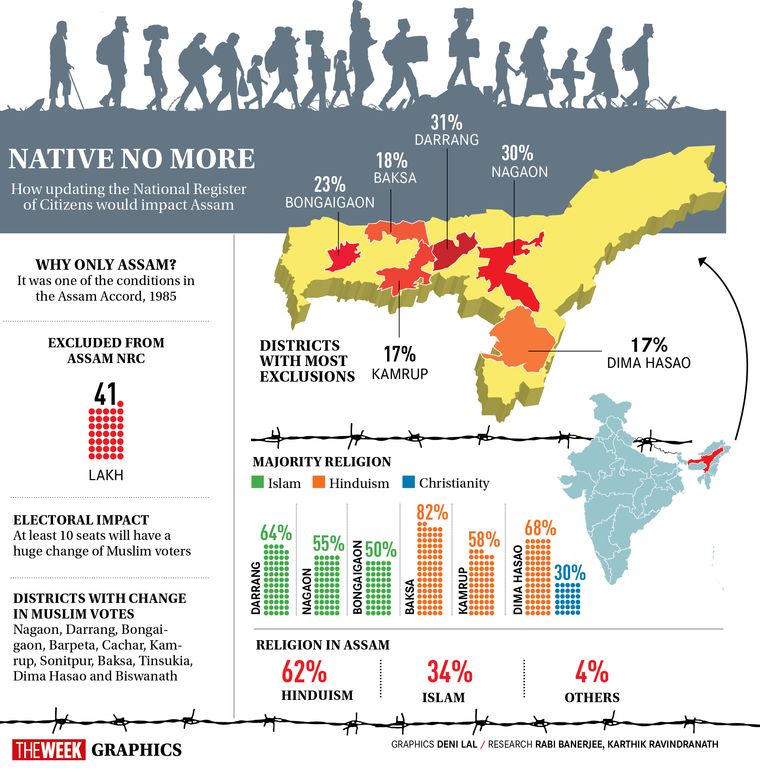

More than 40 lakh residents did not figure in the draft NRC published last year. On June 26 this year, more than one lakh more names were dropped from the list, taking the total number of persons declared ineligible for citizenship to more than 41 lakh. Around 900 people are now lodged in detention centres in the state.

“It means the exercise would never end, and that there could be many more branded as Bangladeshis and deported. What is happening in Assam is horrific,” said Akram Hussein, state coordinator of the Association for Citizen’s Rights, which fights the cases of people who have been excluded.

Interestingly, Sanaullah is not the only Army veteran to be branded Bangladeshi. In 2017, the border police declared that his cousin Ajmal Haque was a foreigner. A retired subedar, Ajmal sought the Army’s help.

“I got their immense support,” he said. “They gave me all old certificates and documents, which I produced before the police. The support of the Eastern Command was huge and the border police was forced to drop my case.”

Sanaullah was staying in Ajmal’s house when THE WEEK met him. According to Ajmal, Sanaullah’s decision to take the legal route was a mistake. “He should have sought help from the Army. But he made the mistake of taking the help of a lawyer and prolonging the case, which landed him in this crisis,” he said.

Sanaullah and Ajmal’s cases date back to 2008, but they had not kept track of the progress. It was only after the cases were handed over to the foreigners’ tribunal, in 2017, that they were notified. Ajmal was notified just after he retired from the Army. “What helped me was that I was posted in Guwahati just before my retirement,” he said. “My retirement papers were cleared from here. So I was able to take help from the Army.”

Sanaullah had also hung up his Army boots by the time he came to know that his case had reached the foreigners’ tribunal. His decision to take legal aid, perhaps, harmed his case because he had failed to inform senior officers of the border police of his plan to litigate against the department. Ajmal said he was also unaware of Sanaullah’s case initially.

According to documents accessed by THE WEEK, the case against Sanaullah was registered on May 23, 2008, when he was posted in Manipur. Sanaullah allegedly told the police then that he was born in Dhaka district in Bangladesh and was not formally educated. According to the report, he admitted that the documents he possessed did not have the real names of his wife and three children. He also allegedly told the police that he was a labourer who did not own land. The transcript of his statement to the police bears a thumb impression, which Sanaullah says is not his own. “If I could become an Army officer, why would I use my thumb impression?” he asked.

The border police had produced statements of three witnesses—Amjad Ali, Kurban Ali and Subhan Ali—to support its finding that Sanaullah was a Bangladeshi. But all three witnesses deny giving such a statement. “The report is completely bogus,” Amjad Ali, a businessman at Kalahikash, told THE WEEK. “Neither was I called by the police and nor did I willingly go to the police station to say Sanaullah is a Bangladeshi.”

Amjad said Sanaullah was the pride of their village. “He is a very upright man and a brave soldier who fought for India in Kashmir,” he said. “We are proud that Kalahikash produced two Armymen—Sanaullah and his cousin Ajmal.”

Amjad and another witness, Subhan Ali, have lodged a complaint against the investigating officer in Sanaullah’s case. “This is how they are labelling several lakhs of Indians as Bangladeshis,” said Subhan, 70. “Our village is proud to have a brave soldier like Sanaullah, who served in the Kargil war.”

Sanaullah, however, told THE WEEK that he had not participated in the Kargil war. “When Kargil broke out, I was posted out of Kashmir to Hyderabad. But it is true that I served in Kashmir thrice in six years—before and after the Kargil war,” he said.

He said it would have been better had he been killed by militants in Kashmir or Manipur. “I would then have got the respect that I am not getting today. Many would have shed tears seeing my dead body. But see where I am today; I have lost my honour,” he said.

Will the public support for Sanaullah result in him getting a permanent reprieve? “It is very difficult, but not impossible,” said Rahman. “One can go to a higher court against the tribunal’s order, but that would be a writ petition and no appeal would be granted. Even the Supreme Court has refused to entertain an appeal. In the writ petition, the higher court will not accept new evidence. Only the evidence that was taken up by the tribunal will be reexamined. If mistakes are found, there is a provision to send the case back to the tribunal.”

Rahman said it would be a legal disaster if the Supreme Court did not step in and make provision for hearing a large number of appeals. “Thousands of courts have been created in Assam to hear the cases related to people who would be declared foreigners,” he said. “But all such cases will be writ petitions. Under Article 226 of the Constitution, [new] factual evidence in writ petitions is not investigated by High Courts and the Supreme Court.”

Sources in the Assam government told THE WEEK that many serving and retired Armymen are in the list of suspects being tried by the foreigners’ tribunal. “There are personnel from the Army, the central armed police forces and even the Assam Police. But such cases are not numerous,” said a police officer.

Ajmal Haque said there were plenty of instances where the border police had made a mockery of procedures. “The investigating officers would not even get out of their offices to meet the accused,” he said. “Their intention is to drive out the Bengali-speaking Hindus and Muslims from Assam. While the Central government has given a lollipop in the form of Citizenship (Amendment) Bill to silence Hindus, Muslims find themselves without any representation in the administration. We are living in the dark completely.”