THE FARMER

Chef Anumitra Ghosh Dastidar and writer Shalini Krishnan travelled around India for nearly three years to collect indigenous varieties of rice that were getting lost. The result was Edible Archives, a culinary project at the 2018 edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. In it, Ghosh Dastidar cooked delicious dishes using 25 to 30 varieties of indigenous rice for the visitors. We met the duo last December to shoot a video of the project. Ghosh Dastidar cooked for us a dish of Hetumari and Tulaipanji rice from West Bengal, accompanied with lentil fritters, cottage cheese, anchovies and fried mackerel. All the different elements in the dish worked beautifully. We polished it off so thoroughly that someone might joke that the mud plate in which we ate did not need to be cleaned afterwards.

While researching the project, it hit Ghosh Dastidar that the aroma of some of the rice varieties she had worked with had subtly changed over time. She spoke to farmers to find out whether it was just her imagination, and discovered the problem. The different varieties of rice were being grown near each other in the fields, and the unique characteristics of each were getting lost. Krishnan explains that when you grow two varieties of rice in adjoining fields, you must make sure that they do not have similar maturation and flowering times, because then, there might be cross-pollination, and the rice varieties will get mixed. “When you dilute the rice, the first thing you lose is the aroma,” says Ghosh Dastidar.

The problem is that, this kind of knowledge has not been codified. It has mostly been passed down orally. And now, it is getting lost. With the spread of industrial agriculture during the Green Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, farmers across India started giving up indigenous varieties of rice for the hybrid varieties which gave higher yields. “There were several lakhs of indigenous varieties,” says Krishnan. “We don’t know how many have gotten lost over time.”

This is not a problem that is just restricted to rice. Namita Gurudas runs AgroTIE, a seven-acre farm and training centre near Bengaluru started in May 2018 to teach farmers how to grow their produce in a scientific way, without the use of so many pesticides and herbicides. Her team visited hundreds of farmers across Karnataka to understand their problems. Currently, in order to train the farmers, they are training themselves with the help of Dutch and Indian experts. They just harvested their first crop of cucumbers.

“The farmers in Karnataka provide only the major nutrients to plants,” Priyanka, a member of Gurudas’s team, tells me. “But micro-nutrients are also important. The farmers we visited were not skilled in crop handling. They did not know how to differentiate between a pest attack and nutrition deficiency.”

Gurudas did not know what to do with the cucumbers, so she contacted a friend, who put her in touch with Chef Manu Chandra, chef partner, Olive Group of Restaurants. Chandra was enthusiastic about trying them out. “These cucumbers have a sweetness that others don’t have,” he told me, as I watched him whip up a cucumber salad using Gurudas’s cucumbers in the kitchen of Toast & Tonic, one of the Olive restaurants, in Bengaluru. “They have no bitterness. They also have a thinner skin and have more applications. You could, for example, cut them open and stuff them with crab meat and it would be a really healthy dish.”

The kitchen was small and functional, and Chandra had to politely ask me to move aside as he hunted for white wine vinegar, sesame oil and perilla seeds that he briskly mixed into the bowl of cucumbers cut into cubes. “This can become the base to which you can add prawns, raw tuna, smoked chicken….,” he said.

Chandra’s salad was surprisingly delicious, considering how simply and quickly it was made. I was slowly coming to realise that healthy food could be incredibly tasty as well. “Our farmers are in a bad shape,” he told me. “They have gotten into a trap in which to increase the yield they need to buy more fertilisers. You cannot propagate the seeds because that is how they are designed. Farmers need more money to produce more, but they are not able to do that, so they keep getting into debt. This is a vicious cycle that needs to break somewhere.”

THE CHEF

Using fresh, local produce, growing organic gardens, and changing menus seasonally are no longer anything new. But a few chefs in India are delving deeper into the concepts of sustainability and farm-to-table. They are focusing on traceability of their produce, making sure it is pesticide-free, increasing the connect with farmers and reducing food wastage. An especially important link in this chain is improving the soil quality of our farms and fields. We need to diversify from rice and wheat to other crops that use less water and are more nutrient-rich.

For that, we need to reverse the supply and demand chain, say some chefs. The farmer should be able to control the demand by supplying the restaurant with whatever is grown in that particular season, rather than the other way around. “What ideally needs to happen is the farmer telling the chef, ‘We have five kilos of padval (snake gourd). Can you use it?’ And the chef finding a way to incorporate it into the menu,” says Chef Thomas Zacharias, executive chef at The Bombay Canteen in Mumbai. Some time ago, a friend asked Zacharias whether he wanted to buy 200kg of black rice from a farm which had a glut of it. Although they used black rice in their sol kadhi ceviche, they did not need that much. So Zacharias came up with a black rice and coconut milk payasam which, he says, became so popular that it is still on the menu.

The Bombay Canteen’s philosophy is to celebrate India’s regional diversity using seasonal produce in a fun way. In the last four years, it has used 120 different vegetables in its dishes, excluding staples like cauliflowers and onions. Zacharias says that going indigenous was a choice he made and not one that was imposed on him. “The problem is that, as the demand for the [rarer] vegetables decreases over time, their diversity gets depleted,” he says.

Also read

I visited The Bombay Canteen with nine of my female cousins on a Friday night in May. We were a boisterous lot, and two gin cocktails down, we grew even more boisterous. The energy at the restaurant matched our own, and soon, it was brimming with customers, with many standing by the door waiting for tables. Almost everything we ordered—the barley and jowar salad, the kali mirch chicken, the Kejriwal toast, and the red snapper ceviche—was richly textured and exploded with flavour. Later, a cousin of mine, who dined out often, told me that Indian restaurants are now moving away from dishes drenched in masala. Chefs like Zacharias have chosen to highlight the flavour profile of each ingredient that they use in the dish, she said, giving the example of the ceviche, made of kokum sol kadhi and black rice murmura.

Many restaurants in India, like the ones in the ITC chain, have adopted sustainable practices to a certain extent. The European grill restaurant at the Grand Hyatt Kochi Bolgatty—Colony Clubhouse & Grill—has partnered with the World Wildlife Fund to help local fisheries get their certification for sustainability.

“Our dream is to have everything produced locally,” says Chef Hermann Grossbichler, executive chef at Grand Hyatt Kochi Bolgatty. “But that dream is not a reality yet because many of the producers are not aware of there being a great business opportunity here. We need the support of the grower and the farmer, and for them to think like us. We are swimming against the current in a world in which everything has gone commercial.”

One of the restaurants which has gone further than most in exploring the concept of sustainability is Masque, a fine-dining restaurant in Mumbai. Chef Prateek Sadhu, executive chef and co-owner of Masque, sources his produce from 40 to 50 farms all over India. He travels extensively through the Himalayan belt, spends time with farmers, comes back to the restaurant, ideates and creates. Although most restaurants in India do not do full justice to the farm-to-table concept, at Masque they have embraced it 100 per cent, he says. That is because there are no fixed menus there. They have a 10-course tasting menu depending on local availability and micro-seasons. In two and a half years, the restaurant has changed menus 44 times. “Restaurants which do a la carte and have 100 dishes on their menu cannot do full justice to farm-to-table,” says Sadhu. “We can. There are so many ingredients to play around with if you just look outside the box.”

According to him, if it was left to the customers, they would mostly order only the classics. Which is why they do not have menus. “At Masque we try to educate people about what they are eating, where it is coming from and why it is important. As chefs, we have the power to create demand.”

He makes an important point about the power of chefs. As Dan Barber points out in his book, The Third Plate, gourmet pizza became a staple at American supermarkets after Chef Wolfgang Puck reimagined it in the 1980s at his fine-dining restaurant, Spago, in Los Angeles, with smoked salmon replacing tomatoes, and crème fraiche replacing cheese. Barber compares a chef to a musical conductor. “One could say that a cuisine is to a chef what a musical score is to a conductor,” he says. “It offers the guidelines for the creation of something immediate—a concert, a meal—that will also ultimately be woven into the fabric of memory.”

But no conductor can make music attractive to a deaf audience. Just like no chef can make a sustainable menu attractive to a people who have no taste for it. Which brings us to the last link in the food chain: the consumer.

THE CONSUMER

An episode of the Netflix show, Cooked, about various cooking methods around the world, profiles a middle-income Indian family comprising the parents and two children—a boy and a girl. As the father comes home from work, the mother and the two children are sitting on a sofa, watching a cartoon channel. Have you cooked anything or should we order? He asks the mother. Order, she replies. “Should we eat KFC?” asks the boy. “Why not?” says the father. “We order food from outside three to four times a week,” he later tells an interviewer. “Right now, the kids are mostly interested in burgers, pizzas…. If it was up to them, they would order food every day.”

This might be an over-simplification of the scenario in India, but it is still a matter of concern. According to a 2017 piece in The New York Times, big food corporations selling processed food are making giant inroads into developing countries like India. “As their growth slows in the wealthiest countries, multinational food companies like Nestlé, PepsiCo and General Mills have been aggressively expanding their presence in developing nations, unleashing a marketing juggernaut that is upending traditional diets from Brazil to Ghana to India,” states the article.

One part of the Cooked episode is shot in Nestle’s Research and Development Centre in Manesar, India. “Nestle spends $2 billion creating innovative products, meeting the changing landscape of our consumers,” says one of the researchers at the centre. “Around five billion noodle cakes are made per year in India alone. In the next 20 years, people will have less time to cook food. We are looking into the next generation….”

This transfer from fresh to industrial is worrisome. According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), the percentage of women in India who are overweight or obese has increased from 12.6 in 2005-2006 to 20.6 in 2015-2016. For men, the percentage has increased from 9.3 to 18.9. As per the research publication, Body Burden: Lifestyle Diseases, launched in 2017 by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Down To Earth, over 61 per cent of all deaths in India are due to lifestyle or non-communicable diseases.

To find a solution to this problem, we need to travel back to our past. Unlike countries like the US, India has a rich food history, with a nutrient-dense traditional diet. “According to me, India had the best diet in the world,” says Leena Mogre, celebrity fitness trainer and director, Leena Mogre’s Fitness. “It was rich in legumes, pulses, leafy vegetables and different kinds of millet. Before we ever heard of quinoa, we had amaranth, which is healthier.”

A few months ago, I visited Ziro Valley in Arunachal Pradesh, home to the Apatani tribe. Although modernity was slowly starting to trickle in, by and large, the Apatanis lived insulated from the rest of the world. The tribe is famous for its sustainable agricultural practices. They practise wet rice cultivation and pisciculture, and also grow millets on the raised bunds between fields. While other parts of the northeast are losing their forests because of the destructive slash-and-burn or jhum cultivation, Ziro Valley is fringed by dense forests. The Apatanis have maintained the fertility of their paddy fields, irrigated by an elaborate network of streamlets. In 2014, UNESCO recognised the valley’s high productivity by adding it to its tentative list of world heritage sites. If the Apatanis can teach us anything, it is that we must minimise our interference in the work of nature. In the tradition of our forefathers, to be truly sustainable, we need to let our land talk.

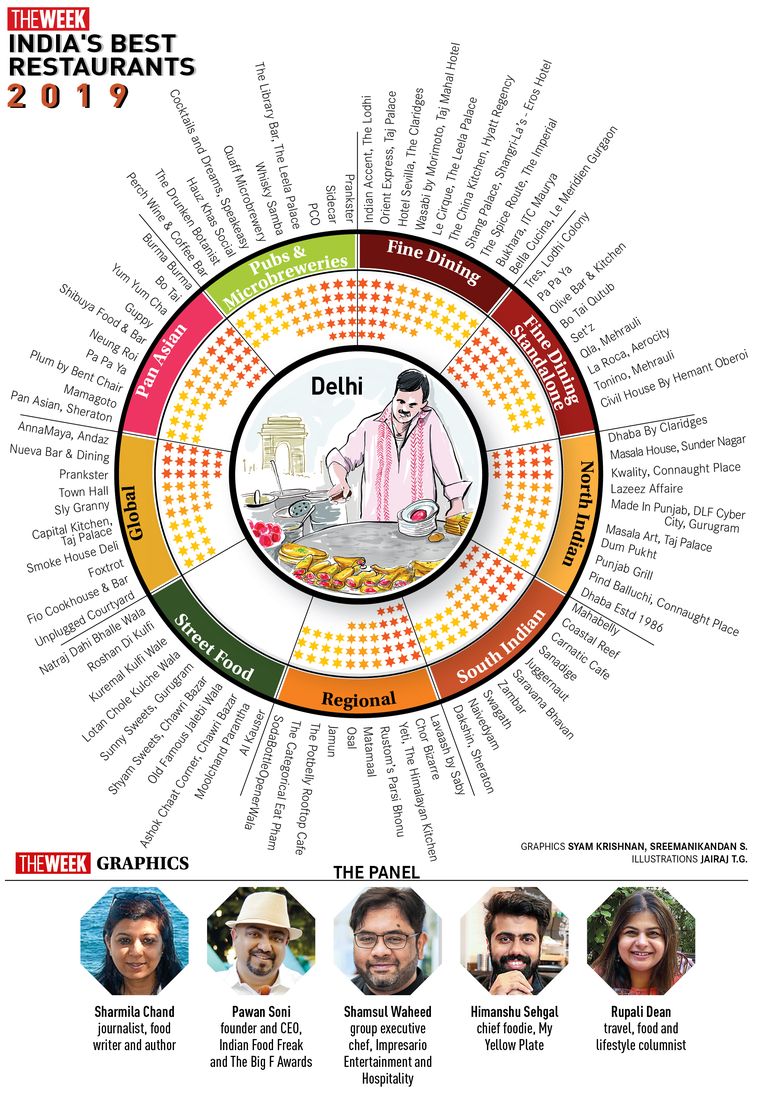

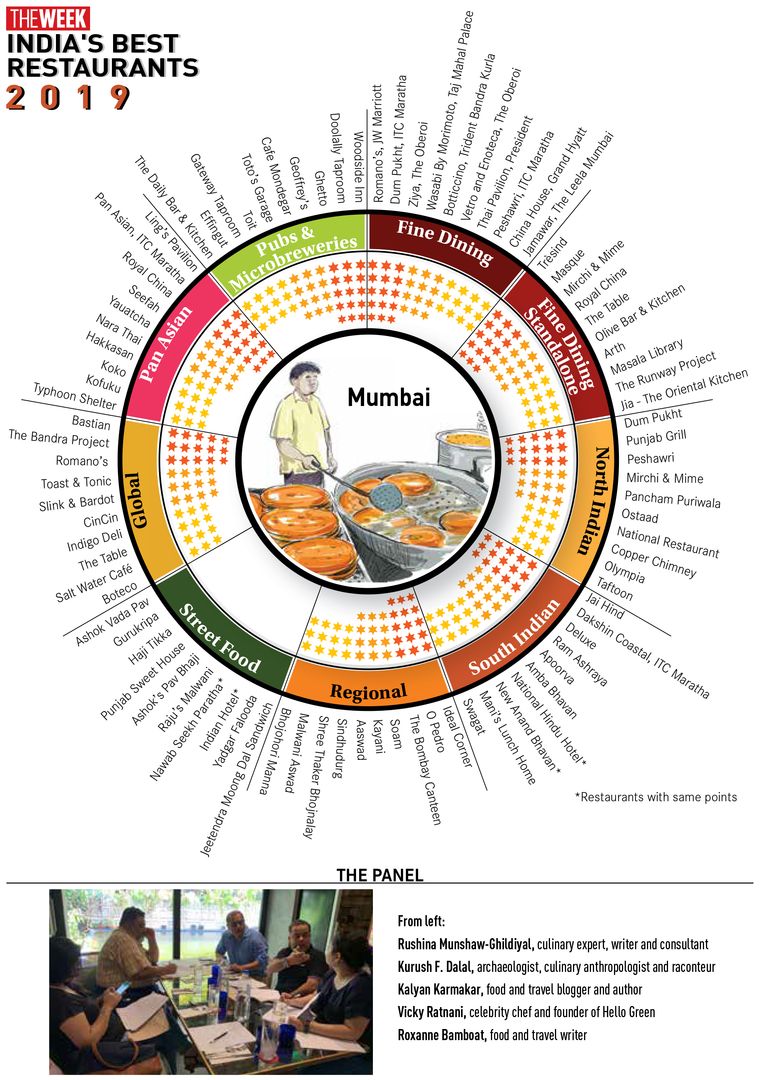

BEST RESTAURANTS 2019

Methodology

THE WEEK correspondents held panel discussions with food experts to rate the best restaurants in seven cities—Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kochi.

The best restaurants for several categories such as fine dining, north Indian, south Indian and global food were selected and ranked by the experts comprising chefs, restaurateurs, food critics, food entrepreneurs, food writers and bloggers, and food enthusiasts. (List of experts given with city-wise graphics.)

Street food is not ranked because the cuisine is vastly different, even within a city. THE WEEK’s Culine Scale was applied to all other categories—five stars for the top 30 per cent, four stars for the next 30 per cent and three stars for the last 40 per cent.