FOR THE PAST three months, Home Minister Amit Shah has been reading reams of Parliamentary documents and meeting a stream of visitors at his office in Parliament House. Ever since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office for the second time in May, Shah’s office has been the centre-stage of activity.

But of late, somewhat strangely, Shah has been a regular in Parliament after 5pm. He would wrap up his work in North Block and host meetings, often after sunset, in a small room inside the Parliament building that could hold a dozen people at a time.

Eventually, on the morning of August 5, Shah took the bull by the horns. He told Parliament that the government was revoking provisions of Article 370 of the Constitution, which granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir, and also bifurcating the state into two Union territories—Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh. The latter would not have a legislature.

The decision had been 72 years in the making. Shah had, at a meeting days before the announcement, apparently said, “We are not a government for five or ten years. We are the Indian government and we are responsible to the people of this country; not from today, but from 1947. We are answerable to them for all the rights and wrongs and we will correct them.”

In Parliament, he said that only a few families had gained from Article 370 and not the people of Jammu and Kashmir. He also blamed the article for the deaths in the state due to militancy—more than 45,000 since 1989—and said it was creating doubts over the state’s relations with India. “We are rectifying a historical blunder,” he said.

No such “historical blunder” has been rectified overnight. And the correction of this one dates back to 2015, when the BJP formed its first-ever coalition government in Jammu and Kashmir with the Peoples Democratic Party. Some senior BJP leaders were against the alliance, but they did not know of Shah’s plan. His trusted team in Jammu and Kashmir—BJP general secretary Ram Madhav, state party president Ravinder Raina and state party general secretary in-charge of organisation Ashok Kaul—was the architect of the alliance. They felt that the formation of a coalition would help the BJP enter the politics of the state by engaging with people at the grassroots level. It would also give them a chance to discredit the Hurriyat, they thought, and expose mainstream political parties such as the National Conference, which had been running dynasties for decades without benefitting the citizens.

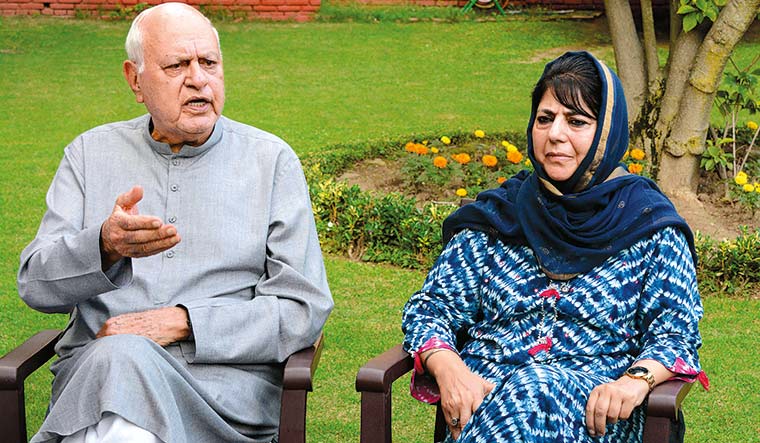

And on June 19, 2018, it was under Shah’s watch that the BJP ended its “unnatural alliance” with Mehbooba Mufti’s PDP. Though the party got brickbats for failing to govern smoothly, BJP insiders said that this was the first time Shah’s Kashmir strategy had tasted success.

Around the same time, the spike in militancy prompted the Centre to break the Ramzan ceasefire and flush out terrorists in Kashmir. More troops were sent to the valley and, for the first time, the National Security Guard was deployed as part of the security grid in Kashmir, ostensibly for training purposes.

Politically, the BJP used the opportunity to blame Mehbooba’s “Kashmir-centric approach”, which it said was made worse by corruption and unilateral decision-making. This, the BJP said, was preventing Central benefits from trickling down.

While the BJP-PDP alliance lasted, the RSS made inroads, gained more access in the valley and engaged with the people there. So, when the alliance finally ended, Ram Madhav had earned credibility in Kashmir. And in the following months, he decided to explore alternative Muslim leadership by engaging with PDP-NC rebels.

The subsequent imposition of president’s rule on June 20, 2018, opened the doors for a slew of appointments that would later become the armoury for the government’s final plan to announce the removal of Article 370. Among them was B.V.R. Subrahmanyam, who was handpicked and sent to Jammu and Kashmir as chief secretary. The Chhattisgarh cadre officer had served in the offices of both Manmohan Singh and Modi, and was an expert in internal security matters. Concurrently, anti-Naxal expert K. Vijay Kumar and former Jammu and Kashmir chief secretary B.B. Vyas were named advisers to Governor N.N. Vohra.

At this juncture, the president appointed Satya Pal Malik, a former BJP MP, as Jammu and Kashmir governor. This was a message to the mainstream politicians that change was round the corner. Instead of a bureaucrat, who tends to follow status quo, a seasoned politician had been chosen.

But this was not all. In October 2018, Malik, for the first time, set up an anti-corruption bureau in the state. The first crackdown was on the 80-year-old J&K Bank, which was plagued by charges of corruption, and eventually led to a notice being sent to Mehbooba, on August 4, asking her to explain her position regarding some appointments in the bank. Incidentally, she had been busy cobbling up support from mainstream political parties to safeguard the state’s special status.

Interestingly, when the BJP allied with the PDP, the Centre also drew up a plan to choke the flow of funds to separatists. In January 2018, the NIA filed a charge-sheet against Jamaat-ud-Dawa chief Hafiz Saeed and also named Syed Salahuddin in it. The NIA named 10 others, including several separatist leaders. Sources in the home ministry said the idea was to not just discredit the anti-national forces, but to also stop them from using money power to engineer fake protests, stone pelting and attacks on security forces.

The arrested Hurriyat leaders were not kept in a Srinagar or Jammu prison, but in far-flung jails in Haryana and around Delhi citing concerns about their security. Notably, this crackdown on separatists and the discrediting of the mainstream parties created a large vacuum for the Modi government to fill.

But, as the Lok Sabha elections were around the corner, Shah and his strategists decided that it was not the right time to remove Article 370.

Interestingly, it was another set of elections, the panchayat polls in Jammu and Kashmir last November, that played a major role in building support for the abrogation of Article 370. Shah’s emphasis on the panchayati system was part of a larger strategy to empower people at the grassroots level. “It was a step in the right direction,” said former home secretary G.K. Pillai, who had told the previous UPA government several times to decentralise power in the state.

So, when Shah told Parliament that Article 370 was an obstacle to empowering citizens of Jammu and Kashmir, his words found resonance among the 4,000 sarpanchs who had been elected in the panchayat polls.

Though Shah was leading from the front, the Centre’s Kashmir strategy had several other important people in the loop, including Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and National Security Adviser Ajit Doval. There was also a battery of trusted lieutenants who had quietly burnt the midnight oil for this day. Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad and Attorney General K.K. Venugopal had mentored the legal team of Law and Justice Secretary Alok Srivastava and Additional Secretary Law (Home) R.S. Verma to legally thrash out the minutest details of the presidential notification needed for the revocation of Article 370. In North Block, Home Secretary Rajiv Gauba and Gyanesh Kumar, the additional secretary in-charge of the Kashmir division, were tasked with coordinating with the state administration and the Central forces to make the bureaucratic process smooth and to maintain law and order. “If the elections are held in an atmosphere of fearlessness and freedom, the beneficiaries will find their political agenda coming to an end,” Jitendra Singh, minister of state in the prime minister’s office, told THE WEEK. “Therefore, sometimes, one tends to believe that these Kashmir-centric politicians are themselves not keen that militancy should come to an end. The people of Kashmir, particularly the youth, want to make the best use of the opportunities made available by the Modi government. Sometimes, it seems the aspiration of Kashmiri youth is stronger compared with their peers in other parts of the country. Which is evident in the past few years, [where we have had] toppers in civil services from the most terror-struck districts of Kashmir.”

In the past, Kashmir has been the baby of the ministries of defence and external affairs, or the cabinet secretariat and the PMO, with each speaking in a different voice. This time, however, was different. “It is for the first time in many years that the home ministry became the centre point for all issues related to Kashmir,” said R.K. Srivastava, former additional secretary handling the Kashmir division. “It is half the problem solved because all decisions rest in one place and the home minister is the right person for it.”

On the security front, the two new intelligence chiefs—Samant Goel, who heads the Research and Analysis Wing, and Arvind Kumar, director of the Intelligence Bureau—became the eyes and ears of Modi and Shah, while Doval volunteered to camp in Jammu and Kashmir to personally oversee all possible national and international ramifications of the move. To beat the intense rumour-mongering across the country and on social media, the BJP sent its MPs on a two-day training workshop on social media. The idea was to camouflage the parliamentary preparation, quipped a party source who recalled Modi sitting among the leaders during the workshop.

But then, on August 2, US President Donald Trump irked India by once again offering to mediate on the Kashmir issue. And, two days later, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan said the time had come to take up the offer. The Centre had to play its trump card soon. Shah chaired a high-level meeting with the home secretary, the IB and R&AW chiefs and Doval on August 4 in the Parliament complex. He was ready for the announcement the following morning.

The last task was to get the numbers in the Rajya Sabha. Four BJP leaders—Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, Railways Minister Piyush Goyal, BJP general secretary and Rajya Sabha MP Bhupender Yadav, and Parliamentary Affairs Minister Pralhad Joshi—played a key role in reaching out to various political parties. They had earlier successfully tested the Rajya Sabha strategy by getting two contentious bills (RTI and triple talaq) passed. Compared with that, Article 370 seemed like a cakewalk.

This was because most non-BJP parties knew that the sentiment outside Jammu and Kashmir was overwhelmingly for the abrogation of Article 370. They favoured the bill lest they be branded “anti-nationals”. And lo and behold, the bill was passed. The Lok Sabha passed it the following day.

“The environment was such that it seemed that any legislation brought by the government after that would get cleared that day,” said an MP on the condition of anonymity.

For Shah, the “integration” of Kashmir into India marks a full circle. In February 2016, he had gone all out against the students of Jawaharlal Nehru University who had allegedly chanted slogans for the freedom of Kashmir. From that point on, the BJP tweaked its strategy to bring in muscular nationalism. It painted everyone who supported the JNU students as anti-nationals.

And now, with the removal of the special status, Shah has taken away the azaadi slogan. At least for now.