India spends a lot to keep the British hale and hearty.

According to the World Health Organization, Indian-trained doctors constitute 9 per cent of all registered doctors in the UK and form the largest group of foreign-trained doctors. There are more than 50,000 Indian doctors serving half the UK population, according to an association of Indian-origin doctors in Britain.

Two years ago, the WHO said that “over 100,000 doctors trained in India were employed overseas, with the higher proportion of these (around half) working in the US, followed by the UK, Canada and Australia”. In Australia, one in five doctors is Indian; in Canada, one in 10.

So, how many doctors does India have?

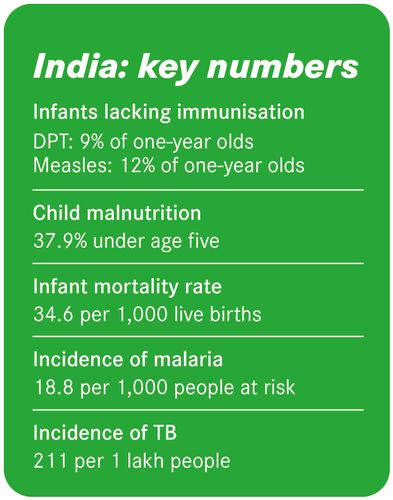

We need around 20 lakh to keep the population in the pink, but we only have around half the number. India produces around 30,000 medical graduates every year, which means that we will not be able to close the gap in 40 years.

The bigger problem is that many of these graduates—often the best of the lot—go abroad for further studies and never return. Consider what happened at AIIMS in Delhi from 1989 to 2000. Of 428 medical students who graduated from the institute in this period, as many as 241 went abroad. More than 60 per cent of graduates from Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh emigrated.

The most disquieting detail is that only seven of 25 graduates who won multiple awards for excellence now practise in India. Apparently, medical graduates from the reserved category are more inclined to work in India than general-category graduates. More than 70 per cent of dalits and tribals who graduated from AIIMS in this period still work in India.

All these figures are from a study published by the WHO in 2008. The brain drain has only worsened since then. In 2011, Union health minister Ghulam Nabi Azad told Parliament that more than 3,000 Indian doctors had migrated overseas in the preceding three years. There was a 40 per cent increase in the period from 2015 to 2017, when more than 5,000 doctors left India.

The panacea for all this is the recently passed National Medical Commission Bill, says the Union government. The proposed National Medical Commission will replace the 86-year-old Medical Council of India, which currently oversees medical education in India. Doctors say the most significant new change is section 32 of the new legislation, which allows 3.5 lakh unqualified medical practitioners to practise modern medicine.

The infusion of these new ‘doctors’ is supposed to bridge the yawning demand-supply gap in India’s health care system. Never mind that most of them may not know the first thing about diagnosis and prognosis.

A sick plan, you say? Yes indeed.