From a statistical point of view, India’s education system resembles a powerful centrifuge—its churn so vicious that a sizeable number of students are ejected at every level of learning.

Here are some figures: Of 19 crore children who take elementary lessons every year, only six crore make it to secondary and senior-secondary levels. Around 2.5 crore become undergraduates, of whom only 39 lakh enrol for postgraduate courses, and less than two lakh pursue MPhil or PhD.

The imbalances are so big that only the cream of India—social and economical, not necessarily intellectual—survive the centrifuge. Case in point: Less than 4 per cent among the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes are graduates, which is far lower than the national average.

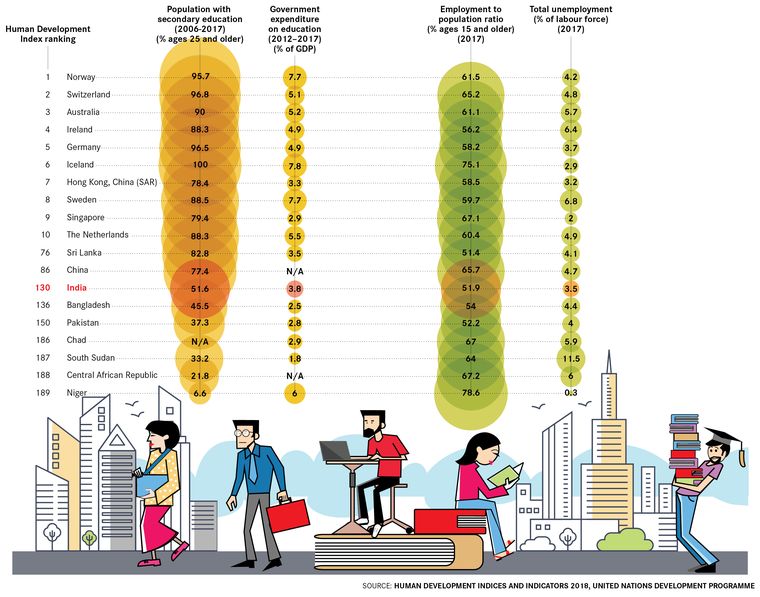

Surely, this is not how public education ought to work. In western European and North American nations, 75 to 80 per cent of the population has at least some secondary education. Even in middle-income countries like China, Sri Lanka, South Africa and the Philippines, the number is higher than 70 per cent. In India, it is 51.6 per cent.

India does not spend much on educating its people. For every Rs100 that the government spends to run the country, the education sector gets less than Rs4. That pittance is meant to fund more than 15 lakh schools, around 40,000 colleges and nearly 12,000 other institutes of learning.

Also read

- Indices: Where India stands in global rankings

- India's demography: All's not well

- Climate change performance index: India rank 11

- Poverty index: India rank 49

- Health care: India needs more doctors

- Human rights a messy issue in India

- Liveability index: No Indian city in top 100

- Gender Gap: Unhealthy to be a woman in India

Compare this to what Thomas Babington Macaulay was paid to introduce English education in India. The value of the monetary compensation he got for his four-year India stint translates to 43.5 million pounds in 2019—approximately Rs375 crore, which is half the annual budget of IIT Bombay.

All is not gloom and doom, though. India’s education system is still the third largest in the world, after that of the US and China. By 2030, according to Ernst & Young, one in every four graduates in the world will be a product of the Indian higher education system. Two decades ago, there were no Indian universities in the global top 200; now there are 23. Open online courses offered by Indian institutes and universities educate 60 per cent of the world’s student population.

India is also among the top five countries in the world in cited research output. There is a caveat, though. Plagiarism and research misconduct among Indian scientists have become so rampant that there is now a dedicated Wikipedia page for it. In 2012, C.N.R. Rao, one of the world’s foremost chemists and a Bharat Ratna, issued a public apology for inadvertently copying the work of other chemists in a research paper co-authored by him. It was not his fault alone; Indian academia has no effective peer-review process that could have spotted the gaffe.

Perhaps, it is time for India to recalibrate that centrifuge.