China and India are the fastest growing large economies in the world, but they have taken different routes to the ultimate goal of economic prosperity. China is propelled by manufacturing (the world’s factory) and India by services (the world’s back office).

Since the industrial revolution, no big economy has developed without undergoing industrialisation. Those that still remain poor have negligible industrial production. India has a good manufacturing base, but not worthy of the size of a $3 trillion economy. And there is an enormous trade deficit in goods. Though India has a trade surplus in services, it covers just 20 per cent of the trade deficit in goods.

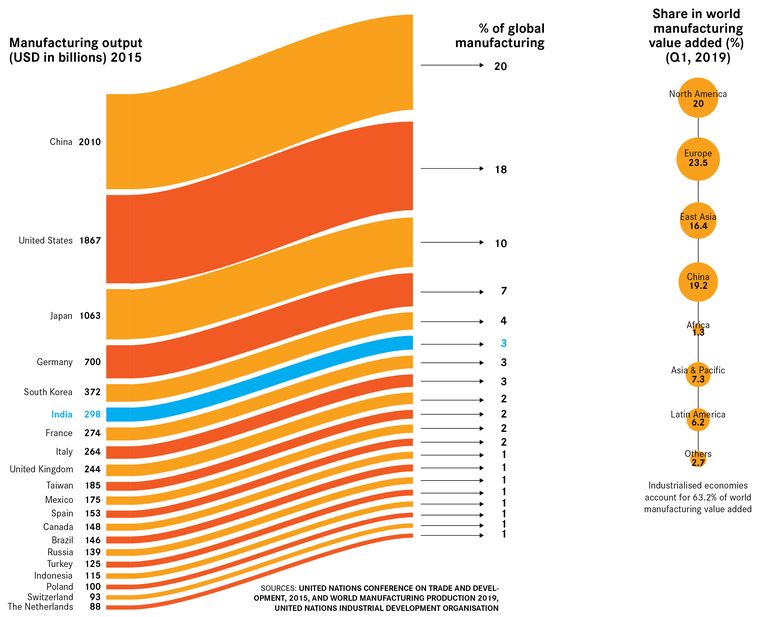

That is a shame for a country which had a thriving industrial manufacturing economy in the 18th century. During the Mughal regime, India produced about a quarter of the world’s industrial output, which was more than what the entire Europe produced at that time. India currently accounts for about 3 per cent of the global manufacturing output, while China’s contribution is around 20 per cent.

The share of manufacturing in the world’s economies has been shrinking in the past four decades, prompting some developing economies to consider skipping the industrialisation phase. India, probably, has made the strongest case for this with an economy riding on the back of services-led growth. It worked for India because of the huge employment generation in the information technology and business process outsourcing sectors.

The catch, however, is that services’ contribution to international trade has been stuck at 20 per cent since the 1990s. That is why Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to make in India. But clarion calls seldom lead to substantial change in the country, and Modi’s initiatives so far have not been good enough to emulate what China has been doing in the past three decades.

Services currently account for more than 50 per cent of India’s economy. But they do not provide the scale and type of employment required to employ the masses—the uneducated and the unskilled. Manufacturing provides such jobs. The National Manufacturing Policy instituted by the government in 2011 was aimed at raising manufacturing’s contribution to a quarter of the GDP by 2025. Currently it accounts for just 16 per cent.

A revival in manufacturing can go a long way in fixing India’s unemployment problem. But that will need massive investment, both domestic and foreign, and policies that will make such investments easier. In fact, it is no longer a matter of choice—we have to make stuff and sell them if we want to do better.