The sun sears down as Vijay Singh surveys the bleak horizon. The past few days have been hot, a sharp contrast to the rains that inundated his farmland in Aneegarhi in western Uttar Pradesh just a week ago. The inconsistency of the weather, however, is just one of his many worries. “Things are just getting increasingly troublesome,” said Singh, who took up farming potatoes and wheat ten years ago. “The output is bad if the weather plays truant, and when the output is good, the market prices fall.”

And it is not just him. “The whole village is in trouble,” he said. “Some are selling their land to pay off their debts.” Singh, 35, is now planning to give up farming and move to a city to make a living, perhaps to Delhi NCR for an office job.

Jageshwar Sharma may not advise that, though. Son of a farmer from a village near Kanpur, Sharma, 22, moved a year ago to take up an assembly-line job through a contractor at a Samsung plant in Greater Noida. At the first whiff of a sales decline this summer, he lost his job. “A thousand of us were fired,” he said. “Being young and educated, I managed to find another job after a few months. But it has been tough for many others to get back on their feet.”

Cut across to Mumbai, you may think investment adviser Aarti Malhotra Chawla’s life is a world apart, but you will be surprised. “The chips are down, with unreasonable regulations and pressure from the government,” she said. “The wealth industry is taking home less and less each year. People are losing their jobs. They have loans to pay, children to bring up. There is a lot of pain on the street.”

HOW BAD IS IT?

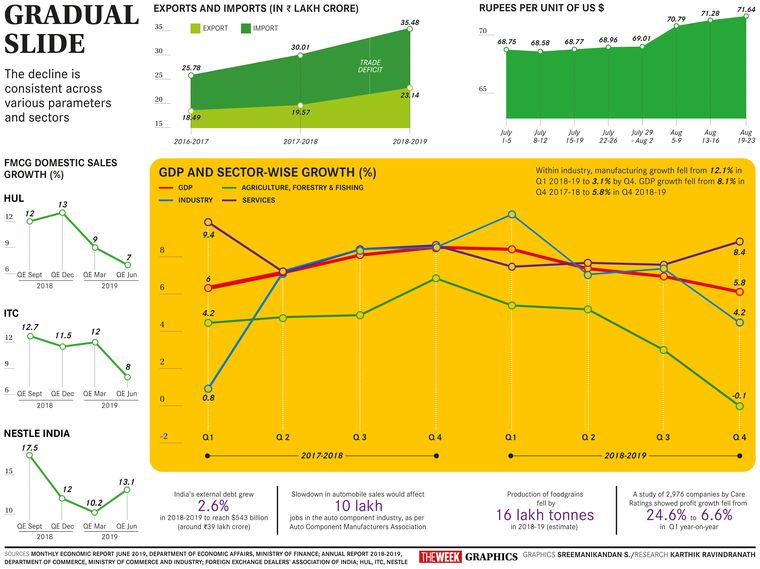

The despair is pretty much visible. Passenger car sales, arguably an indicator of how confident people are about their financial situation, fell by an alarming 36 per cent last month. For about a year now, all categories of vehicles have seen a steady slide in sales, prompting Rajan Wadhera, president of the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM), to bill it the “worst phase India’s auto industry has seen”.

“This is not good for the country, this is not good for jobs,” he said. About three lakh people, mainly in the auto ancillary and business side, have lost their jobs, and with production cuts on at leading players like Maruti Suzuki and Mahindra, there are alarmist projections of ten lakh more people in the sector losing jobs in the months to come. It is estimated that about 286 vehicle showrooms closed down in the past 18 months.

“Both automotive and tractor industries are going through one of the biggest slowdowns that we have seen in recent times; perhaps the last as bad a time was in 2001,” said Pawan Kumar Goenka, managing director of Mahindra & Mahindra. “Retail financing is in problem because of several factors—liquidity, interest rates and banks tightening the norms for financing as per guidelines has led to many customers not being able to avail financing. The overall GDP growth, delayed monsoon, rural spending, rural income, all these are also leading to negative sentiment.”

The auto industry maybe the most vocal, but it is not the only one affected by the slowdown. The real estate market, for instance, is yet to fully recover from the slump that started a few years ago—unsold houses in the top 30 cities rose to 1.28 million as of March this year. The real estate slump goes beyond just sales or pricing—it has a value effect on everything from bank cash flow to infrastructure spending. “Developers are finding it hard to repay their debt obligations because of high inventory and low sales,” said Rahul Grover, CEO of SECCPL, a Mumbai-based realty firm. “Slackened sentiment among property buyers is unlikely to pick up in the near future.”

The crisis in the non-banking finance sector has had an impact on the residential real estate sector. Loans to builders by shadow banks slumped to Rs27,000 crore last year from Rs52,000 crore in 2017-18. “The Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act created a shock in this segment as NBFCs that were giving term loans to the developers stopped financing,” said T.V. Mohandas Pai, chairman of Manipal Global Education and former director of Infosys. “Since there was no money to fund projects it led to the collapse of the sector.”

According to credit rating agency ICRA, more than half of the luxury houses constructed in Mumbai remain unsold. The value of unsold houses in central Mumbai, where several marquee projects have come up in the past few years, is around Rs45,000 crore. The number of active builders in nine major cities is said to have halved to 1,745 in 2017-18 from 3,538 in 2011-12. “The softening in the real estate sector is almost 10 years old,” said Sanjay Dutt, MD and CEO of Tata Housing. “NCR was the first market to go down, that was around the global financial slowdown. After five-six years, Mumbai had excessive supply. When NCR and Mumbai become stressed, the rest of the country goes into a coma, because 65 per cent of the lending in debt is in these two markets. So, the lenders become nervous.”

The story gets repeated across segments. The growth in the fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector, which encompasses everything from biscuits to packaged food to soft drinks and toiletries, dropped to 10 per cent in April-June 2019, declining for the third quarter in a row and indicating that people, especially in the rural areas, are spending less, or rather, have less money to spend. “We can feel the slowdown in discretionary expenditure from the middle class,” said Ravi Saxena, managing director of WonderChef, a home and kitchen products company. “Cash has indeed come down.”

A warning last week by biscuits maker Parle Products that it might have to slash thousands of jobs owing to falling demand suggests that people are even thinking twice before buying a pack of biscuits. Parle’s main rival, Britannia, also noted that the market slowdown was worrying. “We are one-third of the market and we have gained almost 1.3 share points, and we have grown only 6 per cent. So, obviously, the market is growing slower than that,” said Varun Berry, managing director of Britannia, in a conference call with investors.

“(There is) a little bit of decrease,” admitted the government’s chief economic adviser K. Subramanian. “We in India tend to oscillate between irrational exuberance and excessive pessimism. Some sectors are not doing well, but there are other sectors that are doing very well, as well. We have to be careful to look at the aggregates, not just at anecdotes.”

The aggregates are not comforting, either. India’s overall growth decreased to 5.8 per cent in the January to March period this year, with fears that the rate for April to June (to be announced this week) could be worse. And the decline is evident in almost every index of economic activity—corporate investments have been falling, rural income (essentially means what farmers make) growth declined from 27 per cent in 2014 to less than 5 per cent last year and exports and imports both declined by around 9 per cent in June. Even in the automobile industry’s much publicised sob stories, the devil is in the details. The steepest drops are for vans (decline of 45 per cent) and goods carriers (decline of 41 per cent), both crucial as they signal a drop in the economic activity. The growth in the volume of goods freighted by Indian Railways fell from 6 per cent last year to 2 per cent this year.

Inflation also fell from 10 per cent a few years ago to just 1 per cent last month. This may appear to be good news since it could mean a drop in prices. But, persisting low inflation, as it has been for the past two years, means there is weak demand and low consumer interest. From crops not getting good prices leading to rural areas in turmoil to a slump in manufacturing and corporate investments leading to job cuts and reduction in spending in urban areas, India seems to be trapped in a vicious cycle.

WHAT HAPPENED?

Even if one goes by the ‘cyclical’ theory of the economy rising and falling at regular intervals, the human (read government) element also needs to be factored in. The Narendra Modi government’s attempts at fundamental structural corrections over the past few years, ostensibly to clean up the system, have had a direct fallout on the economy. The question is, will the prescribed medicine have the desired curative effect, or is it just a bitter pill causing too many side-effects?

“If we trace back, the slowdown has also been contributed by the rural economy, with farmer incomes dropping and rural wages not growing, leading to a decrease in overall spending,” said Ranen Banerjee, leader (public finance and economy), at the consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. According to Bojja Dasaratha Rami Reddy, general secretary of the Consortium of Indian Farmers Association, demonetisation affected farmers a lot. “At the time of selling produce and investing in fresh cultivation, farmers ended up with no cash,” he said. Coupled with the vagaries of weather and crop failures that regularly happen, the stage was set for a decrease in consumption across rural India.

“The most crucial factor that is reinforcing is that rural wage growth is now barely expanding,” said Soumya Kanti Ghosh, group chief economic adviser at State Bank of India. Hindustan Unilever, India’s largest consumer goods maker, registered a volume growth of 5 per cent in the April-June quarter, less than half of what it did in the same quarter a year ago. Srinivas Phatak, chief financial officer of HUL, attributed the drop to the slowing rural sales. He said rural markets, which were growing at 1.3 times the urban markets, are now growing at par.

If demonetisation crippled rural India, GST came as a body blow to small and medium businesses across the country. “GST is a great thing from a long-term perspective, but in the short term it is stressing out businesses as money is getting stuck and inventories are getting piled up,” said Pankaj Dubey, managing director of Polaris India, which sells the premium motorcycle Indian in India.

THE GOOD NEWS

The silver lining amid all the doom and gloom is that not all areas are as badly affected. Rajiv Bajaj, managing director of Bajaj Auto, even pooh-poohed the ‘fear mongering’ by his fellow industrialists, saying the current scenario cannot be called a ‘crisis’. Maruti Suzuki chairman R.C. Bhargava also put up a brave front, calling the slowdown ‘transient’ as monsoon was good and rural demand should pick up by Diwali, setting the cycle in motion again. India Cements managing director N. Srinivasan even announced last week that the cement industry was entering a ‘golden period’, piggybacking on demand not just in housing projects, but also in infrastructure projects. And, mobile phone sales have been going through the roof. “Smartphone shipments reached a record in the second quarter, with the premium segment growing 33 per cent annually,” said Varun Mishra, analyst at Counterpoint Research.

According to economist Omkar Goswami, there is no recession, “Stop using this term so loosely,” he said. “Gains from liberalisation reforms, which gave us 9 per cent-plus growth, are coming to an end. Time has come for fundamental second generation reforms.”

That may already be happening, if you go by Subramanian. “There is a structural correction,” he said. “If you look at the pre-2014 period, there were [unhealthy habits] like meagre equity, borrowing debt from subsidiary, putting up shares as collateral, just the way in which businesses were being done. We are still undergoing the overhang of it, but we are in the process of reducing and eliminating some of these bad habits. Like, for example, the introduction of the Bankruptcy Code. It has reduced NPAs by Rs3 lakh crore. There is this process of bringing in good habits which is going on, so it makes me sanguine to say that this structural slowdown will actually lead us to better times.”

THE STIMULUS

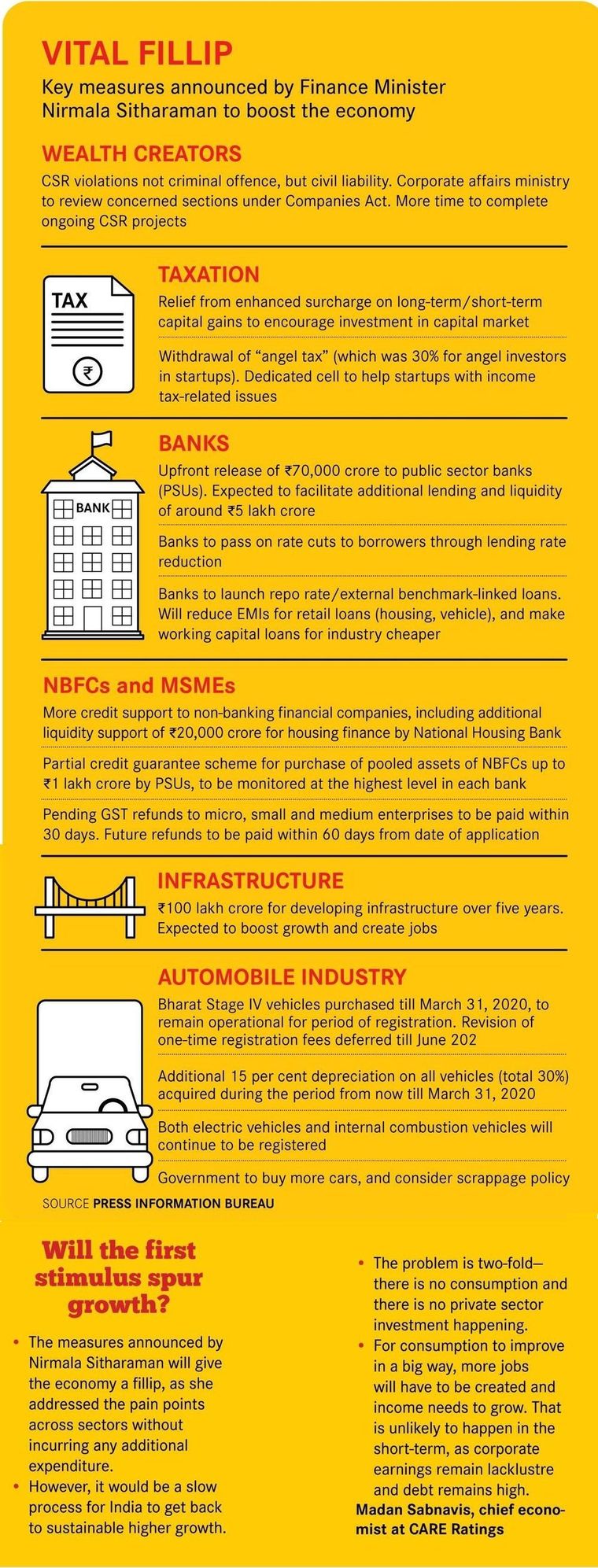

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s stimulus package announced on August 23 could be the beginning of the journey Subramanian mentioned. Again, five days later, the government said it was taking steps to relax norms for foreign direct investment in several sectors. Once the dust settles around the chaos, the many structural reforms set off and the hopes of a more efficiently regulated and smoothly functioning system bears fruit, it could perhaps all be well worth it.

To boost automobile sales, the government is delaying the proposed increase in registration fee till June 2020 and lifting a ban on purchase of new vehicles by government departments. Also, the BS-IV vehicles registered till March 31, 2020, will be allowed to be used for the entire registration period. “These measures will provide the immediate relief that the industry was seeking,” said Venu Srinivasan, chairman of TVS Motor Company. “The promptness of this government’s response is reassuring for not just industry, but for the common man as well, because it is putting liquidity into the market and easing the squeeze on the small and medium sector.”

The finance minister announced booster shots to lift other ailing sectors as well. Housing finance companies will be provided an additional liquidity support of Rs20,000 crore by the National Housing Bank; state-owned banks will be recapitalised up-front to the tune of Rs70,000 crore; and banks will effect timely passage of interest rate cuts to borrowers and link their loan products to repo rates or other external benchmarks. Also, all GST refunds to micro, small and medium enterprises will be paid within 30 days and all GST refunds will be paid within 60 days of filing applications.

Importantly, a proposal announced in the budget to levy a higher surcharge on capital gains on transfer of equity shares, applicable to both foreign and domestic investors, was reversed. There had been a sustained selling by foreign institutional investors post the budget and this announcement has helped calm their nerves.

Sitharaman’s stimulus was different from what was done in 2008, at the height of the global meltdown—no tax holidays, tax deferments or pure financial incentives. The measures would improve liquidity, assure tax payers of fair treatment and help some sectors boost sales. And the markets cheered.

While the recapitalisation of public sector banks would open up the funding channel for NBFCs, linking of loans to repo rates should help consumers avail home loans at cheaper rates, said Niranjan Hiranandani, president, National Real Estate Development Council. “This rejig of the spending model by the government is a clear intent to stoke demand and ease bank credit, which had hit across the industry acutely,” he said.

Under Shaktikanta Das, who took charge as the governor of Reserve Bank of India in December 2018, the monetary policy committee has cut the benchmark repo rate by 1.10 per cent (110 base points). However, rates transmission by banks has been slow. Between April and June, banks reduced their interest rates by 29 bps, even as the RBI had cut repo rate by 75 bps. Following a further 35 bps rate cut in August, several banks reduced interest rates further and some have now started linking their lending rates to the repo rate. “The liquidity easing and repo rate cuts by the RBI will have a positive impact on domestic demand, but with a lag,” said Sonal Varma, chief India economist at Nomura Securities.

The stimulus is clearly a mixed bag. “I am not terribly optimistic, but I am not pessimistic, either,” said Christopher C. Doyle, who runs the company The Growth Catalysts, which has been working with SMEs. “Growth is not just about external demand and the business environment, it is also about building organisational capabilities—technical, human, financial systems and processes. There is a huge problem for the MSMEs on this front.” A stimulus, he said, should include an agency to guide them.

While the promised unleashing of credit may help, industry, trade and corporates were also expecting a rejig in the tax structure, said Doyle. For mid-size companies (Rs250 crore to Rs400 crore) the corporate tax rate is 25 per cent. Adding surcharge and cess, the effective tax rate is around 29 per cent. A new buyback tax of 20 per cent will take the effective tax rate to around 50 per cent. For smaller companies (less than Rs250 crore), the buyback rate does not apply, since they are usually not listed. But their average effective tax rate including surcharge and cess is around 30 per cent.

“The problem in India is that the tax rates remain high,” said Adi Godrej, chairman, Godrej Group. “Former finance minister Arun Jaitley had promised to lower corporate tax to 25 per cent. It has been done so for a few companies. The corporate tax should be reduced for all companies. There is a wrong impression in some sections of the bureaucracy that higher tax will lead to higher collections. Rather, it is lower tax rates that will lead to higher tax collection. Some products that are in the higher GST bracket could be shifted to the lower bracket. Once prices come down, consumption will go up. Once economy picks up, job creation will happen.”

In an attempt to further boost investment, the government on August 28 announced that it would permit 100 per cent FDI under automatic route in sale and mining of coal, 100 per cent FDI under automatic route in contract manufacturing, 26 per cent FDI under government route in digital media and some relaxation in local-sourcing norms for single brand retail trade.

CYCLICAL ISSUES VS STRUCTURAL ISSUES

Even as the steps taken by the government will ease the cyclical slowdown, there will be a lot of structural changes that it will have to initiate to ensure strong economic growth over the long term.

The slowdown has had a direct impact on corporate earnings, which have been weak for some time now. A study of the April-June quarter earnings of 2,976 companies by credit ratings agency CARE reveals that aggregate profit after tax grew just 6.6 per cent. It was 24.6 per cent in the same period a year ago. There was double-digit contraction in net sales across companies manufacturing passenger cars, trucks, aluminium products, and electrical equipment. Similarly, 24 industries, including those in rubber, power, oil exploration, hotels, restaurants, refineries, metals, steel and fertilisers saw net profit decline in the first quarter.

“The current slowdown is a combination of cyclical and structural issues and will take time to fade away,” said Amnish Aggarwal, head of research at Prabhudas Lilladher. “The latest announcements show the intent of the government to remove some of these irritants and structural issues, which will go a long way in preventing incremental damage.”

The government has set sights on making India a $5 trillion economy by 2024. But, that will be a challenge, given that the global growth is slowing down and the trade war between the US and China escalating. “For India to become a $5 trillion economy, one should keep global growth in context,” said Varma of Nomura. “Growth in world trade will be lower due to protectionist policies. If India is to grow faster, then it must increase its market share in exports. At the same time, there will have to be more focus on boosting domestic demand, focusing on infrastructure spending and increasing manufacturing on-shore.”

The Confederation of Indian Industry says a focused export strategy must be devised and domestic manufacturing of the identified products should be aggressively promoted. “A targeted export strategy that identifies and boosts the right products is imperative for achieving double digit export growth,” said Chandrajit Banerjee, director general of CII. “An export strategy assumes greater significance given a rapidly changing global trade landscape, shifting of global value chains and new free trade agreements, including mega trade agreements.”

Despite the slew of measures, given the weakening global growth, stress in the shadow banking sector and weak rural consumption, India’s economy may not see a huge pickup this year. In fact, Moody’s Investors Service has cut the GDP growth forecast for 2019 to 6.2 per cent from 6.8 per cent. “While not heavily exposed to external pressures, India’s economy remains sluggish on account of a combination of factors, including weak hiring, financial distress among rural households, and tighter financing conditions due to stress among non-bank financial institutions,” it said.

So will it be a dark Diwali? While some believe it is too early for a turnaround, many are still hopeful that the only way is up. Puneet Chhatwal, CEO of the Indian Hotels Company, perhaps, sums it up best. “The less bad is the new good,” he said. “Eventually, everything will be alright.”

with Abhinav Singh