Like most Bengalis, he loves classical music, and preferred kurtas to shirts during his college days. He was a brilliant student, who stood first in most examinations. And he can cook a sumptuous meal.

Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee has been described as a jack of all trades by those close to him in Kolkata. But the economist, who has written seven books and can talk at length about various issues, would steadfastly avoid personal questions. “Let it remain within me,” he would say.

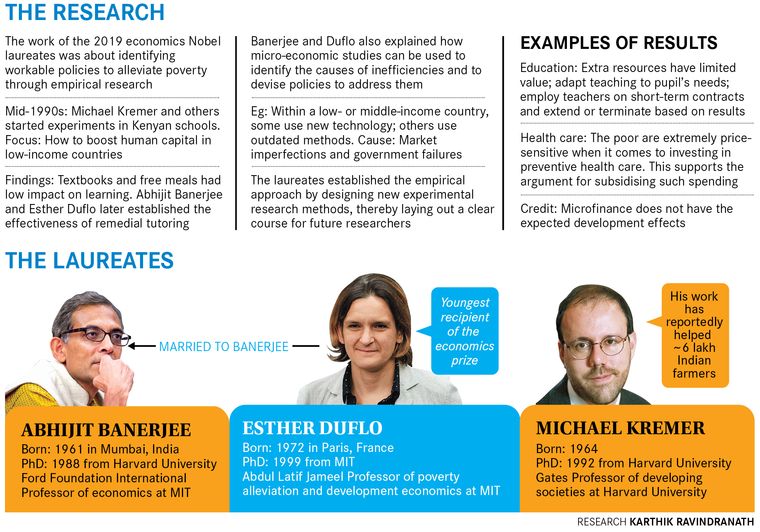

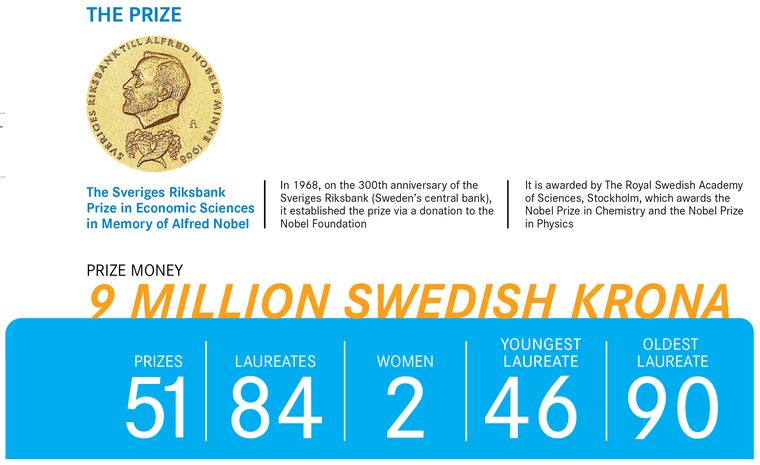

That might not be possible any longer, as Banerjee became the most talked-about man in India on October 14, when the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that he, along with Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer, were the recipients of the 2019 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. The Banerjee residence in the posh Ballygunge Circular Road in south Kolkata has become a favourite spot of the locals. And Banerjee’s mother, Nirmala, has been felicitated for his achievements.

Banerjee, who is the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, lives in Boston, and he is dealing with fame in his own way. “I am extremely busy all of a sudden,” he told THE WEEK. “I do not know how to manage all this.” What Banerjee knows quite well and he seldom refrains from talking about are the troubles in the Indian economy. “It needs immediate attention,” he said.

Banerjee’s father, Dipak, was a contemporary of economist Amartya Sen and was head of the department of economics at Presidency College, Kolkata. Banerjee went to Presidency in the late 1970s, and his father inspired him to study economics. “Almost all the time he scored the highest in the college,” said Abhijit Pathak, a chartered accountant in Kolkata, who was Banerjee’s batch-mate.

At that time, Presidency’s economics department was among the finest in the world. Banerjee, along with Sen and some other illustrious former students, is part of the mentor group formed by the West Bengal government to revive the prestigious institution.

Many blame the Naxal movement in the 1970s for the decline of Kolkata’s grand old institutions. A generation, which would have been the cream today, was lost to the movement. Banerjee is an exception. Perhaps he is the first Bengali academic icon in the post-Naxal era. Maybe that is why he is a talking point in the state, and a reminder of Bengal’s golden period.

Banerjee is a voracious reader. Though he studied economics, he was equally brilliant in mathematics and statistics. He enjoyed literature and was a film buff who loved watching Charlie Chaplin movies or Hollywood thrillers. He was born in Mumbai in 1961; his mother, who is also an economist, is a Marathi. The Banerjees moved to Kolkata when Dipak joined Presidency College.

After Presidency, Banerjee went to Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi. He had cleared the entrance tests of both JNU and Delhi University, but his parents chose JNU because of the excellent faculty. “After 1983 he became a non-resident Bengali,” said Nirmala. “Perhaps he learned cooking then to address his needs.”

After his master’s, Banerjee went to Harvard University for his PhD in 1983. He had taught at Harvard and Princeton University before joining MIT. While at MIT he married Arundhati Tuli Banerjee, whom he had met at South Point School in Kolkata. The marriage did not last long. Their son, Kabir, died in 2016.

Banerjee started his research on poverty in 1995. People did not pay much attention. But he took his study so seriously that many even joked about him looking into everything so closely and spending heavily on the mammoth exercise called randomised experimental work. A decade later, however, the number of volunteers significantly went up and Banerjee had two associates—Duflo and Kremer. He married Duflo, a French-American economist, in 2015. They have two children.

The Nobel committee said that the impact of the work done by the trio could be seen on around five million children in India. Dipankar Dasgupta, former professor at the Indian Statistical Institute who has known Banerjee from his college days, said never before in the history of development economics had such mammoth studies been done. “The experimentation was done mainly in India and in countries afflicted by various problems related to poverty,” he said. “It could be health, it could be education or it could be any other social issue people are faced with. He observed the development closely and showed how help could change the economic scenario.”

Dasgupta said the experimentation was one of the most interesting parts of development economics. “Like in medicine or in psychology tests certain drugs are applied and changes are noticed in patients, he applied the mechanism to cure poverty,” he said. “The idea is to find the potency of certain policies.”

For Nirmala, Banerjee is still a child who grew up fast. “How could I claim him as only my son? He is the son of the nation today,” she said.

Has she gone through the works of her son?

“Not all. Yes, I am also a student of economics, but he learned mathematics more than I did. Certain works by him require higher knowledge of mathematics, which I lacked. But yes, I would love to hear from him,” she said.

It seems everybody is keen to hear from him, and eagerly waiting for his arrival. There will be felicitations and state honours. And the literature books lining the shelves of the little room on Ballygunge Circular Road will be dusted down. So will be the collection of classical music—both Indian and western.