Your Baba was a kind and loving man, who would not hurt a fly. The king was wicked, so he arrested Baba. But do you know what happened then?”

That was how the story would begin. “The wicked king caught and jailed your Baba,” the mother would tell her son, “and made him push the heavy stone chakki (millstones) round and round. Baba did that for many hours, and sat down. And then there was magic, the chakki would continue going round and round, on its own. The jailor was stunned and called the king, who was so stunned that he released your Baba.”

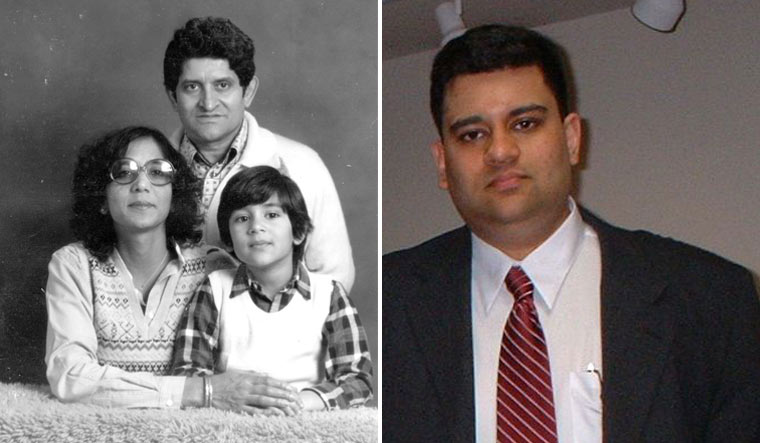

Baba Vikramaditya Bedi, a 16th generation descendant of Guru Nanak, grew up on stories like these. His mother, Chaya Rani Bedi, would also show him portraits of Baba Nanak at their plush US home.

The New York-born Vikramaditya, now 45, sports no turban and has no beard. “The Five Ks came from the 10th Guru,” he says. “My great-grandfather Baba Shib Dayal Bedi would relax these rules in our family, as he believed the five Ks were only for a time of war.”

When Vikramaditya was about four, the giani at their gurdwara pointed to him and told the people he was a descendant of Guru Nanak Dev. “I did not understand what that meant,” he says. “I asked my father, and then began my learning about Nanak Dev, by way of stories my father would tell me.”

Growing up in the US, in the thick of racism and diversity, learning about Guru Nanak was a profound experience for the boy. “Religion was more about learning and accepting differences and understanding what is common to all,” he says.

Though people in the US are curious when they hear of Vikramaditya’s lineage, he says they “[do not] generally understand how advanced his (Guru Nanak’s) thinking was, [and] that he was trying to create a more tolerant world.”

Vikramaditya, a business adviser and writer, is an only child and bonds with his cousins across the world through the religion.

In the 1980s, his father, Dina Nath Bedi, a professor of computer science at The City University of New York, would have Diwali get-togethers for the Americans. “But there was limited understanding of Indian history,” says Vikramaditya.

His father had grown up in their ancestral home in Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, but went to the US for higher studies in 1957. “[Later,] he did a joint venture to establish computer training in India,” says Vikramaditya. “He was appointed by Indira Gandhi to the science and advisory commission of India, along with M.N. Dastur.”

Though he has never lived in Saharanpur, Vikramaditya remembers the Uttar Pradesh town fondly. “In our ancestral home, there are murals that are over 150 years old,” he says. The descendant intends to launch an outreach programme in India to mark 550 years of Guru Nanak, in November, and make it an annual event.

Like all descendants of Guru Nanak today, Vikramaditya traces his lineage to him through the guru’s son, Baba Lakhmi Chand. The guru’s other son, Sri Chand, was an ascetic who never married.

The descendants prefix “Baba” to their name to indicate their lineage. Apparently, during the rule of Mughal emperor Akbar, who was a follower of Guru Nanak’s teachings, “Baba” simply meant descendants of the guru. In Dera Baba Nanak, a region in Punjab settled by Baba Dharam Chand (Guru Nanak’s grandson) as a home for the Bedi clan, they are referred to as ‘Guru Ansh’ (having a part of the Guru) and Babas, out of respect.

Guru Nanak was a big-time traveller, and his descendants have a global presence and outlook. In terms of work, they occupy important positions in all fields, especially in the military.

Retired Major R.S. Bedi, a 15th generation descendant of Guru Nanak, says three 14th generation Bedis served in the British-Indian Army during WW II, and were taken prisoners of war by the Japanese forces in Singapore. One 13th generation family member, Risaldar Dalip Singh Bedi, was even awarded the Jangi Inam, a gallantry award, by the British government.

The family is so steeped in military history that Baba Prithpal Singh, a 14th generation descendant, apparently gave references of six brothers, five cousins and three uncles when he applied for a job in the military.

Given their family history, the Bedis, who live in the national capital region, have not found it hard to teach the next generation about their lineage. “Everyone in our Bedi family has a family tree that is prominently displayed,” says the retired major. “We also have documents of our ancestors, and the children grow up knowing their connect, all the way back to Guru Nanak Dev.”

The bearded and turbaned Bedi, 69, along with his two younger brothers, runs an international freight and logistics business.

World over, there are about one lakh Bedis who trace their roots to Guru Nanak. And apart from Dera Baba Nanak, some descendants also live in Una, Himachal Pradesh. Before partition, some families had moved to Kallar near Rawalpindi, where there is still a Bedi Mahal. There is also a Bedian village, and the oft-used road from Lahore to this village is called the Bedian Road. A canal crossing this village is called the Ravi Bedian canal.

The legacy every Bedi inherits, says the former Army man, is the message of Ik, or oneness. “It is a beautiful message by the great Guru that Ik, oneness, pervades and interpenetrates every part of the universe and also extends beyond space and time,” he says.

The Bedi Foundation, set up by Baba Prithpal Singh Bedi, is involved in the education of young girls and slum children, langar seva, sanitation and cleanliness projects, and assistance to the needy for medical expenses.

Major Bedi continues to make the trip to Dera Baba Nanak almost as if it were a pilgrimage. A visit to the Chetram family, living in Amishaian Galli there, is all any Bedi has to do to trace his lineage. For generations, this family has been the keeper of the Bedi family tree. Written in Gurmukhi script, it is up to date till the 17th generation. Major Bedi says there may be some toddlers of the 18th and 19th generation elsewhere in the world. They will possibly become part of the record in the near future—the 550th anniversary in November will see many Bedis from all over congregate at Dera Baba Nanak.

Proud of the lineage though they are, the Guru Nanak descendants do not see him as a hero of the family, but as the guru of the universe. And all of them have the same reason to do so—Guru Nanak Dev did not name either of his sons as his successor. Says Vikramaditya, “While realising that he is our ancestor, we do know he experienced a divine awakening. Until such a thing happens to us, he shall remain in a league of his own.”

Guru Nanak’s other son, Baba Sri Chand, also lives on in the lives of the descendants. At all their weddings, the Bedi boy is dressed like an Udasi sant, like Baba Sri Chand, in the presence of a mahant (priest) from an Udasi akhara. Only later does he wear the clothes of a groom. This is a custom exclusive to the Bedis.

The descendants of Guru Nanak, like everyone else, have political views, but have kept away from politics—be it national, Akali or separatist. Dina Nath Bedi did go to Kartarpur in 1945. But his son Vikramaditya, who was invited to visit Kartarpur, says he will go only when India-Pakistan relations normalise.

The Bedis wonder how their forefather would have reacted to the world as it exists today. He would be appalled to see the loss of oneness, the absence of inclusivity and the divisive forces that are splitting the world, says Bedi. Vikramaditya says he would find the world has become more humane in certain aspects, such as health care and technology. But he would be disappointed with the history of the past 400 years, the world wars, the atomic capacity and the violence.

Like there has been no living guru after Guru Gobind Singh, there has never been another Nanak in Guru Nanak’s family, out of respect for the first Guru.