Satara in western Maharashtra was once the seat of the Marathas. They fought and won many a battle here. The fort of Pratapgarh, where Maratha king Shivaji Bhosale outsmarted the mighty Bijapur general Afzal Khan, is not too far from here. The entire nation is now marvelling at how another Maratha strongman, Nationalist Congress Party supremo Sharad Pawar, outsmarted the formidable BJP. But, very few know that the battle began at a public meeting in Satara.

Pawar, 79, was speaking to a large crowd at an election rally on October 19 when the skies opened. Even as younger leaders ran for cover, he did not move. “The rain god has blessed the NCP, and with the blessings Satara will create a miracle in the polls,” he told the crowd. It was a powerful image, and it showed that he would not give up without a fight.

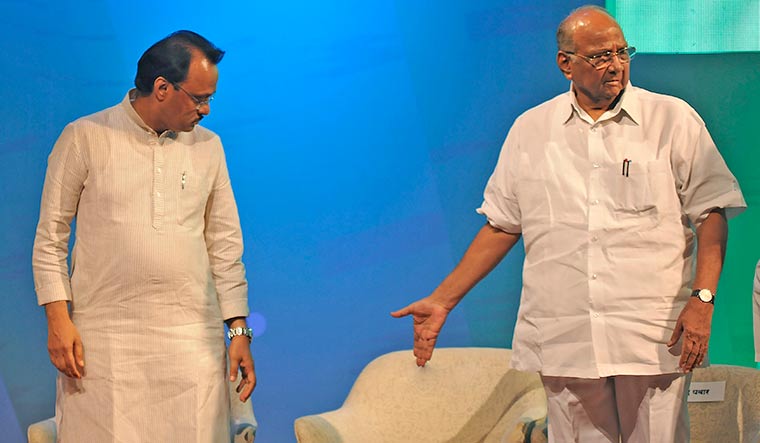

Ahead of the polls, the NCP had seen an exodus of leaders to the BJP and the Shiv Sena. Pawar was unfazed, and was at his combative best throughout the campaigning. There was high political drama when the Enforcement Directorate filed a money laundering case against him and his nephew, Ajit, along with some other politicians, in the Maharashtra State Cooperative Bank scam. The case re-energised the party and a strong message was sent across the state that Pawar was being defamed.

Pawar’s fighting spirit got the NCP 54 seats and its ally Congress 44 in the assembly elections. Even when the talks between the BJP and the Shiv Sena on government formation turned bitter, he remained cautious and reiterated his decision to sit in the opposition. But when the Shiv Sena cut ties with the BJP and said its doors were open, Pawar responded. He met Congress president Sonia Gandhi in Delhi, exploring the possibility of an alliance.

When the governor invited the NCP to form the government, after the BJP and the Sena had failed to do so, Pawar sent a letter stating that his party was not in a position to do it. The letter was sent hours before the deadline given by the governor, and the Sena and the Congress were not happy about it. Pawar had rightly anticipated that the governor would impose President’s rule for six months and that would give him ample time to cobble together a coalition. He then opened a channel with Sena leader Sanjay Raut and convinced the saffron party that a common minimum programme would have to be worked out.

As the talks went on, Ajit demanded that the NCP should ask for the chief minister’s post for two and a half years. Pawar, however, ruled out the demand. One theory is that Pawar did not want his nephew to become the chief minister because of the ED case against him and the investigation into the irrigation scam. And, he could not have offered it to anyone in the party other than Ajit.

In 2004, when the NCP won more seats than the ally Congress, Ajit wanted an NCP leader to become the chief minister. But, Pawar settled for some key ministries. In 2009, there was a demand that Ajit be made the deputy chief minister. Pawar, however, let Chhagan Bhujbal retain the post, since the Congress had continued with Ashok Chavan as the chief minister. Ajit’s wish was fulfilled in 2010, when the Congress replaced Ashok Chavan with Prithviraj Chavan. Ajit, however, resigned soon amid a tussle with the chief minister over irrigation issues, a move that angered uncle Pawar.

In the meantime, the graph of Pawar’s daughter Supriya Sule was on the rise. In 2006, Pawar called her back from Singapore, where she and husband, Sadanand, had settled in. Pawar vacated his Baramati Lok Sabha seat for her in 2009 and contested from Madha.

When the Congress-NCP alliance lost the assembly elections in 2014 and the Shiv Sena and the BJP could not reach an agreement on the post of the chief minister, Pawar offered to support a BJP government from the outside. He had said on several occasions that no one was untouchable in politics.

Of late, Ajit has been upset that while no stone was left unturned to ensure Supriya’s reelection from Baramati in the Lok Sabha elections a few months ago, the same was not done for his son, Parth, who lost from Maval. Later, the selection of Amol Kolhe, who had come to the party from the Shiv Sena in March, to lead the NCP’s Shiv Swarajya Yatra across the state also miffed him.

Ajit’s decision to join hands with the BJP was not taken overnight. In a meeting of the party’s core committee on November 17 in Pune, he and a few supporters argued that it would be better for the NCP to support the BJP. But it was opposed by leaders like Jayant Patil, Jitendra Awhad and Dilip Walse Patil. And Pawar decided to go with the Shiv Sena, which was considered the lesser of the two evils.

Ajit lost his father, Anantrao, early, and had to drop out of college to take care of the family. The people of Baramati still remember seeing him on his farm and at the local agriculture produce market committee. He became the chairman of Pune District Cooperative Bank and the Lok Sabha member from Baramati in 1991. He vacated the seat for his uncle two years later, when Pawar became defence minister in the P.V. Narasimha Rao government. He became a legislator in 1993. When the NCP was formed in 1999, it was Ajit who convinced many young leaders to rally behind Pawar. He became a minister in the Congress-NCP government in 1999.

This time, however, Ajit could not convince many to stay with him. Even the close aides who had backed his decision to join hands with the BJP returned to the Pawar camp in a day. Ajit’s maternal cousin Jagdish Kadam is a trustee of Deccan Education Society, which runs many colleges in Pune and is closely associated with the RSS. This connection is said to have come to play in his decision to go with the BJP.

The turf war between Ajit and Supriya has been brewing for some time. An able administrator, Ajit has for long been seen as Pawar’s successor. But Supriya’s rise had made him uncomfortable. It might be the reason he took the extreme step. Now that everybody has kissed and made up, Ajit might just lie low and bide his time.