In his epic poem Raghuvamsa, Kalidasa conjures up an enchanting image of the Sahyadri, describing the mountain as “a comely young maiden”. A young boy in Pune read the poem many times over 15 centuries later and fell hopelessly in love with the comely young maiden. He would stand on the terrace of his house, gazing at her for hours as she, clothed in majesty, lay stretched across the horizon. The boy in love, Madhav Gadgil, was barely ten years old then.

“I fell in love with that beautiful image in my first reading itself,” said Gadgil, 77. “My love for her has only grown stronger.” It is a lasting love that has shaped his entire being.

Dressed in a wrinkled light blue Payyannur khadi kurta and dhoti, Gadgil was seated in the study of his book-filled fifth-floor apartment in Pune. Tall and slim, he had a calm demeanour, though one could sense an argumentative mind beneath his peaceful countenance.

His study table faced the Sahyadri, and a cool breeze wafted through the open windows. Numerous awards and citations lay scattered around in the room, not given much importance. A copper water jug and steel glass stood on a coffee table. On a corner table stood a statue of Bal Gangadhar Tilak, whom British colonists had called “the father of the Indian unrest”. An unframed Madhubani painting and a Picasso print hung on the walls. Tall wooden bookshelves were stacked with books of multiple genres.

The Sahyadri is better known as the Western Ghats, but Gadgil prefers the former name. “While Sahyadri evokes lots of feelings and connects you with one’s collective cultural past, Western Ghats is a plain and mundane name given by the British,” said Gadgil.

Born in 1942, he was deeply influenced by his father, the famous sociologist and economist Dhananjay Ramchandra Gadgil. A Cantabrigian, the senior Gadgil was a famed institution-builder, but a firebrand who boldly criticised Mahatma Gandhi on policy matters in 1946. And when it was time for his son’s upanayana (thread ceremony), the senior Gadgil refused to conduct it. “We are not Brahmins,” he declared.

The son breathed in that spirit of being different. On a visit to the Gadgils’ home, the economist Wassily Leonteif asked 12-year-old Gadgil what he wanted to do in his life. “I want to become a biologist,” Gadgil said. Leontief quipped: “Wonderful! Never do what your father does, especially if your father is any good at what he does.”

Gadgil’s teachers, peers and family friends were dismayed when the brilliant student, who had topped the board exams, opted for biology at Fergusson College, Pune. Even his teachers at Fergusson advised against it, considering poor career prospects, but he had the whole-hearted support of his father. “My father always encouraged me to follow my heart without any misgivings whatsoever,” said Gadgil.

What was his mother like? “My mother [Pramila] was a simple soul,” he said. “Though she was a deeply spiritual and religious person, she never allied with the wrong practices in Hinduism. She was also very involved with women’s rights issues.”

He fondly recalled his neighbour, the sociologist Iravati Karve, who instilled in him a love for fieldwork. “As a child, I was fascinated by the material she brought from her fieldwork,” he said. He was only nine years old when he had gone on his first field trip with Karve to Kodagu district in Karnataka, where she had a month-long research assignment. “My school principal refused to allow me a month’s leave but my father told me to go.” His father nurtured his love for the outdoors and introduced him to bird-watching at a young age.

Though his primary interest was science, Gadgil enjoyed reading all sorts of books. “My father had a huge library,” he said. “Sanskrit poetry and Maratha history were his favourite topics.” Through school and college, Gadgil was a keen athlete. “I was a champion high jumper,” he said, with a chuckle.

After studying biology for his bachelor’s degree, Gadgil took a master’s degree in zoology from Bombay University, and then did his PhD in ecology at Harvard University. He had loving company at Harvard; his newlywed wife, Sulochana, a Pune girl, too was at Harvard for a PhD in mathematics.

Was it a love marriage? “Well, it was love from my side, at least,” said Gadgil, with a laugh. “Our photos had appeared jointly in a university magazine as we had topped our respective courses. I showed the photo to my mother, as she had been insisting I get married before leaving for the US, fearing I may end up marrying a firangi [foreigner]. But I was too shy to propose to her.”

Asked about the proposal, Sulochana said: “I didn’t remember him, particularly. When the proposal came, however, I was only too happy to agree as the Gadgils were known as the nicest and most progressive family in Pune.” Three months after their wedding, they left for the US.

“Sulochana was a tremendous asset,” said Gadgil. “I breezed through the maths classes only because of her.” He frequently had bouts of self-doubt, however. “Harvard was full of bright students from across the world, so I was not sure of where I stood,” he said. “But one day in the elevator, I met Ed Wilson, a pioneer in ecology, and he complimented me on my excellent performance. From that moment onwards, I never doubted myself again.”

Gadgil was among the first generation of biologists to use computers, and he won the IBM Fellowship to the Harvard Computing Centre. The late sixties, he said, was an exciting time, with the Vietnam War and hippies catalysing lively intellectual debates on campus. After completing their courses, Gadgil received job offers from both Harvard and Princeton University, while Sulochana received an offer from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The couple, however, decided to return to India. “Both of us were absolutely certain that we wanted to live in our country,” said Gadgil. Sulochana concurred. “I told him if we were going to stay on in the US, we would not have children,” said Sulochana. “He was happy, as both of us were on the same page.”

Tuning in to the conversation, their daughter, Gauri, quipped: “Many scientists get a temporary assignment in the US simply to have their kids there. Ours must be the only parents who wanted to come back to India to have kids.” Gauri is a journalist, while her younger brother, Siddhartha, is a professor at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru.

After they returned to Pune in 1971, Gadgil got a job at the Maharashtra Association for the Cultivation of Science, and Sulochana, at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology. Gadgil had little to do at his workplace since the laboratory facilities there were elementary. So he made plenty of field visits to his favourite place, the Sahyadri.

Two years later, the couple joined the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru. “It was the best place to be, for any committed scientist in India,” said Gadgil. “We had a great team, led by eminent theoretical physicist George Sudarshan, and there were endless debates on evolutionary biology.”

But the call of the Sahyadri was too strong, and he soon found reason to return. Gadgil spearheaded the first census of south India’s wild elephant population and began an investigation into the social behaviour of tame elephants at the forest camp. “Wild elephants roamed this great forest, and I very quickly learnt Kannada when my tribal guide shouted “ane bantu” [elephants are coming] and we had to run for our lives.” Once, he spent an entire night up a tree, while a wild elephant hung around below.

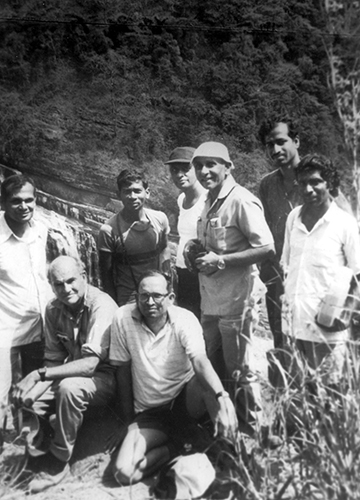

In 1980, the government’s department of environment asked Gadgil and scientist Kailash Malhotra to study the major environmental problems facing India. They travelled the length and breadth of the country; the Western Ghats, the Himalayas, the Thar desert, central Indian forests and the farmlands of the Deccan. They then presented a report that for the first time provided a masterly overview of the various forms of environmental degradation in contemporary India.

Observing elephants had piqued Gadgil’s interest in another area, the study of bamboo. “I was fascinated by the life cycle of the bamboo, so when the Karnataka government asked me to look into the concerns of basket weavers, who were worried about the overexploitation of bamboo by the paper industry, I jumped at the opportunity,” said Gadgil.

“I gradually learnt that forest managers told many tall tales and knew little of what was going on in the complex ecosystems,” he said. “Also, I learnt the harsh truth that industrialists were in the business of making money, not paper. They did not care if bamboo stocks were decimated forever. While these people looted the environment, the local people, who cared for the ecosystem, were beaten up. That really affected me.” This realisation added an activist dimension to his academic persona.

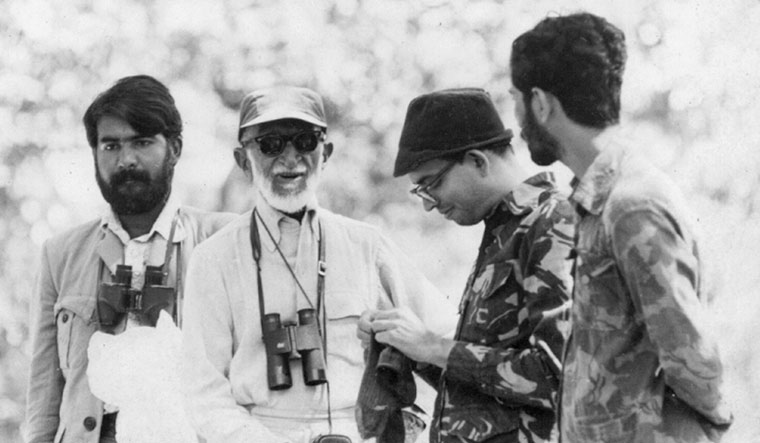

Around the same time, he also worked with the ornithologist Salim Ali, and was part of an advisory committee constituted by prime minister Indira Gandhi on environmental issues.

Through his work, he realised how unscientific and irrational was the manner in which development projects were often cleared in India. “While on a committee to assess the environmental impact of a hydroelectric project on the Bedthi river in Uttara Kannada district in Karnataka, I went on a field trip with an engineer from Rajasthan,” recalled Gadgil. “I noticed that a large bloodstain was slowly spreading across his spotless white shirt and quickly realised that a leech at the project site must have bitten him. When I drew his attention to the blood, the poor man got the shock of his life. Coming from dry Rajasthan, he had no idea what a leech was. When I told him that such creatures thrive in tropical rain forests, he was aghast at my foolish notion that such forests were worth saving.”

Has he ever regretted returning to India after his stint in the US? “Yes, once,” he said. “During the Emergency. I am strongly democratic, and authoritarianism is something I will never tolerate. Thankfully, the Emergency ended in two years.”

The door bell rang, jolting us back to the present. “It must be the doctor who has come to check my blood pressure,” he said. “I am an old man, you know.”

Gadgil still looks fit and healthy, however. All those hills he climbed on the Sahyadri have kept him so. He goes for long walks and is always ready for a trek. He practises yoga and eats sensibly, ragi and fish being his favourite food. “I like everything about fish,” he said. “Even fish pickle.”

He said that his surname and the tag of being an environmentalist had some disadvantages when it came to food. “People assume that I am a vegetarian and always book me a vegetarian meal when travelling,” he said. “So while all my friends get sumptuous non-vegetarian meals, I am fed some grass and paneer.”

Does he believe in God? “My father was an atheist; I think I am also an atheist, though not the aggressive type,” he said. “I am yet to see a justification for believing in divine design, I suppose.”

When my eyes darted to the images of the goddess Saraswati on his writing table, he said: “I have no issues with gods.” He then smiled and pointed to an image of the god Ganesha in a corner. “If I have a soft corner for one god, in particular, it is for the Buddha. I consider him to be the greatest son of our country. He himself was an atheist.”

Gadgil narrated an incident that had influenced his attitude towards religion. “When I was 12 years old, I went on a trek to the Sahyadri along with a friend. It was summer and we were very thirsty. We found a temple on a hilltop that had a well. When we requested the priest for water, he asked us if we were Brahmins. My friend belonged to the mali [gardener] caste. I replied that neither of us was Brahmin. Hence, we were refused water. That day, I decided not to have anything to do with a religion that stops someone from giving water to a thirsty 12-year-old boy.”

Gauri said that the only advice her father gave her when she was of marriageable age was not to marry within the caste. Gadgil’s son in-law, Kiran Shah, later thanked him for this advice. “I am a biologist and I know the advantages of cross-breeding,” said Gadgil, with a laugh. His son, Siddhartha, too, probably received the same advice; his wife, Ulka, is from Bengal. She is an engineer.

Gadgil has been called a Gandhian, a communist and a socialist. “I have huge respect for Gandhiji, but I also felt that he was inconsistent on many issues, and that he was anti-science and technology,” he said. Does he identify as a communist or socialist? “I strongly believe in human equality,” said Gadgil. “If that makes one a communist, then I am one. But I strongly disagree with the authoritarian nature of communist parties. As I mentioned, I am deeply democratic. So I will not fit into the communist bracket either.” After a moment’s silence, he said: “It’s better if you call me a humanist, or maybe an incurable optimist.”

On the balcony adjacent to his study, there were numerous pots of tulsi plants; only tulsi and nothing else. In a corner, lay a statue of the Buddha in bhoomisparsha mudra, where the fingers almost touch the ground. “I connect most with the Buddha,” he said. “In this particular posture, which is my favourite, by pointing to the earth, the Buddha is indicating that his enlightenment comes not from any divine sources, but from Mother Earth.” The statue was custom-made by a sculptor in Karnataka.

Currently, Gadgil is preparing to write a book about the events that unfolded after the submission of the 2011 Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel report (Box on Page 32). “After that, I may write my autobiography as many people are urging me write it,” he said. What might its title be? He replied: “How about, In Love with Life?”