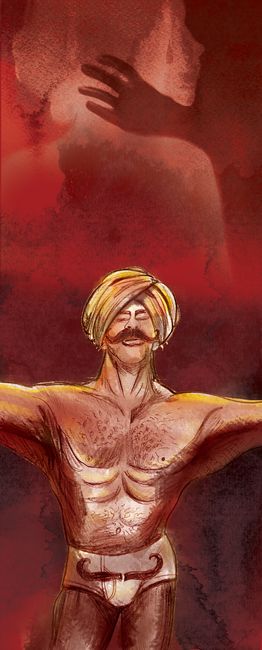

Dipu Raja Yadav knew he was a Very Important Person from the moment he was born. Being the only boy of six children, he was the ‘raja beta’ everyone had been praying for. In the stolen moments I got with his mother, she spoke of the desperate fasts she had kept for a son. So when Dipu was born “by the grace of god”, the midwife beat a brass thaali in ecstatic announcement. Savitri was finally the mother of a son. And, the village pandit was summoned for as lavish a pooja and feast as the family could afford.

Eighteen-or-so years after Dipu’s birth, I travelled to the border of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh to meet this man-child, out on bail for participating in a gang rape.

***

Let me give you some Rape 101: the dominant discourse about the cause of sexual and other forms of violence is that their perpetrators fail to acknowledge the humanity of others. This ‘other’ can be conceived of as another individual or group, or as the philosophical concept of ‘the other’ in relation to and different from ‘self’, which Simone de Beauvoir and others after have applied to the man-woman binary construct and sexual inequality.

Either way, the core idea behind this belief is that one can perpetrate crimes on others only because we do not see them as human, but as different from and less than human. We, therefore, talk about the ‘dehumanisation’ and ‘objectification’ of women—the denial of women’s autonomy, agency and humanity—as the cause of sexual violence.

“The thesis that viewing others as objects or animals enables our very worst conduct would seem to explain a great deal,” wrote Paul Bloom in his masterly article ‘Beastly’ on perpetrators of violence in The New Yorker. “Yet, there is reason to think that it is almost the opposite of the truth.” This school of thought—that much violence is because of, not in spite of, the recognition of the humanness of the victims—is worse. In Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, philosopher Dr Kate Manne proposed: “Often, it is not a sense of women’s humanity that is lacking. Her humanity is precisely the problem.”

Here, I offer a humble contribution to the discourse on violence: both ways of looking at victims, dehumanised or all-too-human, are causes of violence. It depends on the individual perpetrator’s agenda with that individual victim in that particular instance.

***

Psychologist Dr Nicholas Groth, in Men Who Rape: The Psychology of the Offender, said that in all rape, three components are present: power, anger and sexuality—their hierarchy and interrelationships vary. Here, too, I propose that all motives—for sex, power and anger—are causes of rape; and that it depends on the perpetrator’s agenda with that victim in that particular instance. For instance, in marital and relationship rape of the garden variety (that is, sans violence or anger), they dehumanise their victims for sexual fulfilment. When in doubt, he asserts his personal interests over hers. He is the entitled, superior human; she is denied the right to make an autonomous decision about participating in sex.

But the victims are seen as all-too human in cases of public gang-rape.

***

It was a regular “fun” evening for the boys, which started with Dipu hanging out and getting drunk with his older, history-sheeter cousin Arjun. However, this evening, unlike their other habitual outings, ended with a gang-rape and the subsequent police complaint that would alter the lives of the cousins and their two friends (and, primarily, the survivor and her family). The boys moved on to a gambling game, where they got more drunk. Some friends invited them to a local den, where they had some rustic food and drank even more. It was 10 or 11pm, and someone suggested they call it a night. Arjun said he had to collect money he was owed from a man called Pintu, who had been avoiding him. “We told him that if we go at this time, we would cause a fight. But he insisted,” said Dipu.

Pintu snuck out the back as soon as they arrived at his house. His wife, who used to be a dancer, opened the door and said her husband was not in. This enraged Arjun and, led by him, the four of them raped her at her doorstep. When Pintu reappeared, they beat him up, too. No one dared stop them.

Both factors that Dipu identified as causes of this gang rape—“a consequence of company” and because they were all drunk—have been well documented across the world.

***

The idea had been to punish Pintu through his wife’s gang-rape, the premise being that a family’s honour lies in the vaginas of its women. That ‘honour’ is seen as inseparable from the chastity of women holds true even when she exercises sexual agency. From a patriarchal perspective, rape is a crime against the ‘owner’ of the woman. It is a familial and societal shame.

In What We Talk About When We Talk About Rape, Sohaila Abdulali, a survivor of gang-rape in Mumbai, said of rapists who hurt the woman while the man watches helplessly (as had been the case with her): “The whole scenario is a toxic blend of machismo and cruelty, a neat way of pressing every button related to what it means to be male and female.... If you want power and control, and all the research says that is what much of rape is about, then, if you manage to rape a woman and bring a man to his knees at the same time, it must be a double victory.” Pintu’s punishment for delaying the return of around Rs5,000 to Arjun was the public gang rape of his wife.

Here, it is apparent that the survivor was seen as fully human, and power assertion and anger were the perpetrators’ primary motivations. It is the same when rape is used as a tool of politics, war and civil conflict, deployed against countries and communities—as it was during Partition and the Gujarat riots. Called ‘genocidal rape’, it can also be seen in the Kathua gang-rape case—apparently, the perpetrators wanted to distress and displace the eight-year-old girl’s nomadic community through her prolonged disappearance and the ultimate discovery of her brutalised body. But, through all these instances, there is no denying the sexual pleasure derived by the perpetrators. The police charge-sheet reveals that one of the accused in the Kathua case, policeman Deepak Khajuria, told another to wait “as he wanted to rape the girl before she is killed”.

***

Rapes by strangers are no more than five or six per cent of the total number of rapes; gang-rapes by strangers are even less frequent; and stranger gang-rapes with murders are rarer still. Although stranger gang-rapes and murders are not the norm—marital, relationship and acquaintance rapes are—this is the type of rape that gets our attention, from the Delhi gang-rape to the recent Telangana and Unnao cases. This is problematic, because episodic news coverage and selective outrage is part of the problem. It muddies the water when it comes to the idea of rape and consent. It takes a law and order approach to solving the rape crisis in India. It has a caste-religion/class angle to rape by strangers—the ‘Shakti Kapoor’ idea of rapists, ‘the other’ loutish men lurking in bushes, waiting for ‘good’ Savarna women to come along. But I digress.

Gang-rape by strangers happens, of course. An incisive report published in 2018—‘Women’s Safety in the National Capital Territory of India’—proposed ‘migrant anxiety’ as a reason for increasing incidents of gang rapes and groups engaging in violence against women in public spheres of Delhi. Migrants feel “othered” by insiders; further “[u]nemployment in the city creates a sense of isolation and powerlessness… exacerbated by constant exposure to an unattainable lifestyle.”

“The nature of public rape is changing,” observed Dr Abhijit Das of the NGO MenEngage Alliance. India has been deeply hierarchical for millennia, and most rapes tend to follow class lines, top-down—men targeting women of their class or lower—except when the power dynamic is occasionally subverted. Explains why, when a friend was molested in public by a man not of our milieu, her friends caught him and demanded: “Teri aukaad kaise hui[How dare you touch a woman above your class]?”

Top-down gender violence continues as it always has. These are some leads I did not pursue, shared by a cop I spoke to over a couple of years: the son of a taxi driver became a doctor in Mumbai, and also married a doctor. When the couple visited his village in Uttar Pradesh, a Thakur and his sons tied the wife to a tree and raped her in front of her husband because they “could not handle a poor taxi driver’s son being an MBBS”. Despite being reassured by her husband, the woman jumped from the train near Igatpuri and died. Another: in order to usurp a poor farmer’s land, a powerful landowner got five-six men to gang-rape the farmer’s wife and two daughters. The family left the village.

But public rape now includes another dimension—lower-class men targeting upper-class women. “The poor, uprooted, rural man, exponentially disempowered in the city, is lashing out at those he thinks are the reason for the problem,” said Das. This type of rape carries elements of genocidal rape—asserting power, instilling fear, expressing anger and, of course, sex. These perpetrators also fit the ‘Anger Rapist’ category as defined by Groth. For them, the rape experience is one of “conscious anger and rage, and he expresses his fury both physically and verbally. His aim is to hurt and debase his victim, and he expresses his contempt for her through abusive and profane language.... Sex becomes his weapon, and rape constitutes the ultimate expression of his anger”. And we seem to be breeding mobs of them.

***

Aside from the rage resulting from migration and money issues, the report on women’s safety in Delhi also listed the clash of cultures as a major reason for the city’s problem of gang-rapes by strangers. Migrants are unable to distinguish the public roles of city women from that of rural women. “A decent girl would not roam around at 9 o’clock at night…. Housework and housekeeping is for girls, not roaming in discos and bars at night,” said Mukesh Singh, a perpetrator in the Delhi gang-rape, in India’s Daughter. These migrants bring ideas and norms of what is accepted and acceptable in the hinterland to the urbanised, modern world—where patriarchy and misogyny in thought, word and deed collide with women’s empowerment. They experience a clash of cultures and clothes, not to mention the porn they are watching and the accompanying urges—all the while being in extreme close proximity to women as tailors, guards and drivers.

***

There are no quick or easy answers to the rape crisis unfurling in India today. The solutions are hard work. They include, but are not limited to, introducing comprehensive sexuality education; reducing economic inequality; changing the police and legal systems; and revolutionising social structures. But the solutions do not, by any stretch of imagination, include the police murdering rape accused in their custody.

Kaushal is author of the forthcoming book Why Indian Men Rape.