ONE DAY IN the late 1990s, when engineer K. Vaitheeswaran was browsing the web, he noticed an advertisement for books. He clicked on the ad and landed on a website called Amazon.com. Astonished by the business opportunities offered by the internet, he quit his job at Wipro and started India’s first e-commerce company in 1999, along with five others. From a single room with a desktop computer at the Newsbridge Business Centre in Bengaluru, the six intrepid entrepreneurs launched Fabmart—an online platform to sell music cassettes.

From writing content and collecting payments to packing and shipping items and handling refunds, the Fabmart founders had to learn everything from scratch. Many of the problems were solved with jugaad ideas. Signing up music labels, for example, was a herculean task as no one knew of Fabmart or understood its concept. Unable to get the metadata of songs, the entrepreneurs bought just the cassette covers from the label. Similarly, to copy the content on to Excel sheets, they rented a marriage hall, spread bed sheets on the floor and hired interns to scan the cassette covers and enter the data. “Things are infinitely more convenient today,” writes Vaitheeswaran in his book, Failing to Succeed: The Story of India’s First E-Commerce Company. “E-commerce companies get well-structured and formatted metadata from book publishers and music or movie companies which they upload in bulk on the website at the click of a button.”

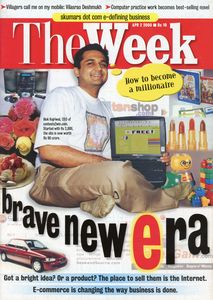

Fabmart was one of the companies THE WEEK had profiled in 2000 in its cover story Brave New Era (April 2, 2000), about how e-commerce was changing the way business was being done. By then, e-commerce had started flourishing in the country. Things peaked when Sify acquired Indiaworld from Rajesh Jain for Rs499 crore. After that, internet companies started mushrooming everywhere. On an average, one new website claiming itself to be the ‘first’ to offer some new service or product was coming up every day in the big cities. “Dedicated retail online stores offer the A to Z of business to consumer (B2C) products, from automobiles to zippers,” stated THE WEEK. Some of the popular portals included Jaldi for shopping, Snehaquest for matrimonials, Dhadkan for music and Automart India for second-hand vehicles.

None of these portals were, however, destined to last long. The dot-com boom and bust of 2000 took place at record speed when Nasdaq touched incredible highs on March 10, 2000, creating, as Vaitheeswaran writes in his book, “thousands of paper billionaires and millionaires”. A month later, on April 14, Wall Street experienced its biggest single-day fall, triggering the dot-com bust. Fabmart, which later became Indiaplaza, was one of the startups that lasted the longest, surviving 9/11 and the global economic meltdown. But it had to shut shop in 2013 when it ran out of working capital, out-funded by companies like Flipkart and Snapdeal.

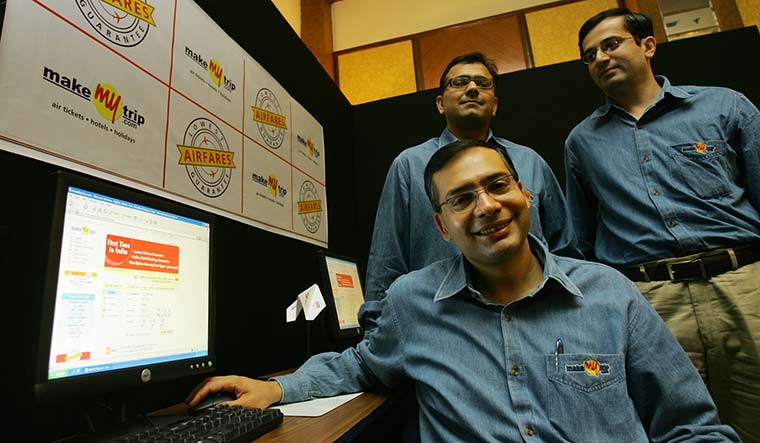

Interestingly, one of the few online companies from 2000 that continues to perform well today is MakeMyTrip, whose founder and CEO Deep Kalra was bitten by the dot-com bug in 1999. “I was convinced that the internet would change everything we were doing,” he says. “And then, solving real world problems through the internet became my raison d’etre.” His was one of the last companies to get funding before the dot-com bust. Afterwards, eVentures, the company’s first investors, wanted an exit. Kalra had two options—either return the money or buy the company back. With the help of friends and family, he managed to buy back MakeMyTrip. But within six months of the launch, Kalra realised that Indians were using the platform to search for travel options but not to book them because they were wary of online cash transactions. Immediately, he realigned his strategy to focus only on inbound travellers—mainly NRIs living in the US. “We also discontinued marketing within India—and in hindsight, it was one of the smartest decisions we took as a company,” he says. “This approach worked well. We hit our numbers and were ready for the next million.”

After the 2000 frenzy, the second-wave of e-commerce happened post-2009, when it was easier to get access to the internet and smartphones were getting popular. The industry became flush with investor funding. Post-2014, according to a 2018 report by the management consulting company Redseer, e-commerce entered the ‘acceleration phase’. There was some consolidation and players started targeting profits. “In 2015, the industry was scattered with many players like Snapdeal and Shopclues, which constituted the larger share in the market, while Amazon’s onset left other players to lose their market share,” states the report.

Things have changed drastically since the launch of Fabmart, when its co-founders would order one music cassette a day so that there would not be a single day without any sales on their website. E-commerce transactions have increased from $100 million in 2000 to around $32 billion in 2018. From one million people with internet access in 2000, the number has increased to over 450 million today. In 2000, Fabmart made an average of 30 sales a day. Today, Flipkart makes almost one million shipments a day.

Despite the rapid growth of e-commerce over the last 20 years, online shopping still represents only 2.9 per cent of total Indian retail sales, according to a 2019 J.P. Morgan report. But the market has huge potential and companies like Amazon and Flipkart are on a focused mission to exploit it. According to Amit Agarwal, country head of Amazon India, India is at a unique turning point. In the next five years, the country will grow to be a $1 trillion digital economy powered by the world’s largest and youngest mobile internet base. Millions of small and medium businesses will embrace technology and become digital entrepreneurs. “Our approach in India is centred on empowering the unique and large base of small and medium businesses to serve customers,” he says. “Over 5.5 lakh sellers offer more than 200 million products on Amazon.in, reaching customers in 100 per cent of India’s pin codes, and millions of products are eligible for next-day guaranteed delivery.”

Rajneesh Kumar, chief corporate affairs officer at Flipkart, says that the next 500 million users who will come online are going to be very different from the current base. He believes that tier-II and smaller cities are going to contribute 85 per cent of new users, with women and youth forming a key segment in future. Also, there is going to be an explosive growth in users wanting to access the internet in their native languages. Almost 30 per cent of all searches in India are already voice-based, and this figure is expected to go up with an increasing number of users uncomfortable with typing. These users are likely to be not so affluent with less access to credit. “We are investing heavily in technology to solve these [issues], be it by making the e-commerce experience available in native languages, solving for shopping through voice or [offering] different payment constructs to help the next half a billion people get access to credit,” he says.

Further ahead, the future of e-commerce might lie in predictive analysis, feels Vaitheeswaran. “E-commerce companies will offer shoppers products which they are likely to buy in future and attempt delivery before they order,” he told THE WEEK. Sounds too far-fetched? Considering his first idea turned into a multi-million dollar industry in India, perhaps we better sit up and take note. Especially as Amazon got a patent in 2013 for “anticipatory shipping”.

E-COMMERCE TRANSACTIONS

2000 - $100 million

2018 - $32 billion

INDIANS WITH INTERNET ACCESS

2000 - 1 million

2019 - Over 450 million