Last week, when Congress leaders exhorted him to rethink his resignation as party president, Rahul Gandhi told them that he would have, if only they, too, had quit with him. Apparently, Rahul was miffed that most of his general secretaries had shied away from taking the blame for the rout in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

There was, however, one leader who had stepped down with Rahul—Jyotiraditya Scindia. The young general secretary had quit as the party in-charge of western Uttar Pradesh; the Congress had scored a duck there in the Lok Sabha elections.

But now, Scindia has gone one step further, quitting the party altogether.

When Scindia had given up his post along with Rahul, he wanted to be rewarded for his loyalty. Instead, over the months, he found himself being ignored, if not punished. It stung him, yet he stayed on for close to ten months.

But then, on the morning of March 10, the day his father, Madhavrao Scindia, would have turned 75, he drove to the Lok Kalyan Marg residence of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, where Home Minister Amit Shah was also present, and ended an 18-year association with the Congress.

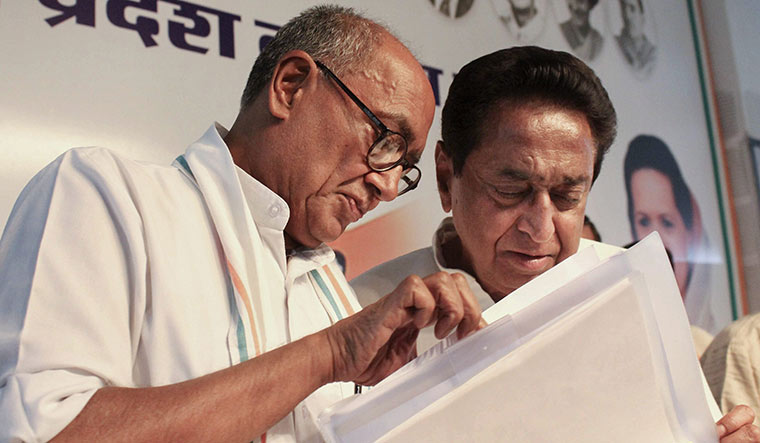

The seeds had been sown months ago. It was not just that Scindia felt shut out of the power dynamics in Madhya Pradesh, which is dominated by Chief Minister Kamal Nath and senior leader Digvijaya Singh. It was more a result of the breakdown of trust and the snapping of communication lines between him and Rahul.

It seems that Rahul did not like Scindia’s calls for an urgent settlement of the leadership issue, and his statement that the party should collectively decide on who its new president should be. Moreover, the fact that Scindia supported the abrogation of Article 370 and wanted the Congress to adopt a nuanced approach to hindutva did not go down well with Rahul.

Sources close to Scindia said that he did not get an audience with Rahul for months together; the last time he tried was five months ago, and then he gave up trying.

Critics say the party leadership failed to act in time to assuage Scindia. The problems began in December 2018, when he had expected to be named state unit president ahead of the assembly elections. He settled for the post of campaign committee chief. After the election win, which was in part due to the party doing well in the Chambal-Gwalior belt, where he holds sway, Scindia lost out on the chief minister’s post.

The biggest jolt, however, was his Lok Sabha election defeat in Guna, a family stronghold, at the hands of a former aide. Following this, he found himself being sidelined further.

The Scindia episode is indicative of the change in party dynamics after Rahul made way for mother Sonia to become party president. With the old guard calling the shots and with Rahul being “unresponsive”, Scindia, like several other young leaders, had found himself on the losing end.

“It was the duty of the Congress leadership to intervene in the matter and resolve it,” said former Mumbai Congress president Sanjay Nirupam. “However, there is a feeling that this kind of intervention is not taking place.”

Sources close to Scindia said that he was hurt at the manner in which the party high command had ignored his pleas. He had hoped to become state party president after Kamal Nath was made chief minister, and even warned that if he was not given the post, he could look for other options. It was in a bid to placate him that he was made party in-charge of western Uttar Pradesh prior to the Lok Sabha elections. In August, he was made chairman of the screening committee for the assembly elections in Maharashtra, but this proved to be far from placatory.

Scindia made his restlessness known as he intensified his visits to Gwalior from Delhi, taking the Shatabdi Express thrice a week and coming back by the evening train. He changed his Twitter profile in November, highlighting his passion for cricket and deleting the reference to the Congress. Last month, he even declared that he would hit the streets if the Kamal Nath government did not keep its manifesto promise of giving compensation to teachers.

Then came the last straw—Scindia wanted a nomination to the Rajya Sabha, but he was reportedly turned down. As was his plea to meet Sonia. It seems that Kamal Nath and Digvijaya, who have better traction with the high command and with the senior leaders who form Sonia’s team, were able to convince her that Scindia’s demands were disproportionate to his achievements. He could not do much damage to the party, they said.

But, unbeknownst to them, Scindia had been in touch with the BJP for more than a year. In January 2019, he had raised eyebrows by calling on former chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan in Bhopal. He had then called it a courtesy visit.

Said Congress general secretary P.L. Punia: “It is unfortunate that a person whom the party gave so much has joined the BJP. There should be introspection on the reasons for such a big leader leaving. It is not a sudden development.”

Rajya Sabha member B.K. Hariprasad, however, criticised Scindia, saying that he, as general secretary in charge of Madhya Pradesh, had offered Scindia the post of state party president in 2010, but the latter declined. “He wanted to be made PCC chief just a year before the polls (2013),” said Hariprasad. “He wanted to continue as minister. Such conditions were not acceptable.”

Though it is debatable whether Scindia was reasonable in his demands, the party is bound to feel the impact of his departure. While it marks the likely demise of the Kamal Nath government in Madhya Pradesh, one of the few states where the Congress is in power, the optics of the exit are also damaging. Scindia was the flag-bearer of his father’s legacy. A four-time Lok Sabha member, he was known to be close to the Gandhis. In fact, before he lost the Lok Sabha election, he was Rahul’s fiercest supporter in the lower house, aggressively shielding him from the barbs hurled from the BJP benches.

According to a young party leader, who recently quit as a state unit president, Scindia’s exit tells the story of the problems in the party. The young leaders, he said, were finding themselves at a grave disadvantage in the tussle with the old guard.

“Jyotiraditya finally took a decision,” he said on condition of anonymity. “Had he spoken out for me when I faced problems in my state, I would not have had to leave. I fear that many other young leaders are likely to follow suit.”

Scindia’s cousin and former Tripura Congress president Pradyot Deb Barman was more outspoken on the issue. “I love Rahul Gandhi,” he said. “But he really left us to fend for ourselves. We were in the party because of him, and he just became unresponsive to our issues after he resigned as party president. I wanted to speak to him, but he changed his number. He has changed his number three times. How does one get in touch with him?”

Another young leader and former Union minister said there were others in the party who felt the same way as Scindia did. These circumstances, he said, might force them to look beyond the party.

In Rajasthan, for instance, Deputy Chief Minister Sachin Pilot, who doubles as state unit president, has had frequent run-ins with Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot. It was under Pilot’s stewardship that the party had won the assembly elections in 2018, but the party high command picked the more experienced Gehlot for the top job, making Pilot feel cheated.

Gehlot, however, seems to be far better placed in terms of his support base and numbers than Kamal Nath, and the BJP would have to undertake a far more challenging project to pose a threat to his government.

Interestingly, Gehlot, who faces a challenge from the restive Pilot, had choice words for Scindia. “The Congress gave him so much for 18 years,” he said. “And when the occasion arose, he proved to be a rank opportunist.”

Other leaders identified with team Rahul, such as Milind Deora and Jitin Prasada, have been striking discordant notes. If Deora lavished praise on the AAP government’s handling of its revenues, Prasada backed the idea of a law on population control, which the BJP is allegedly planning. Nirupam has strongly criticised the old guard for targeting leaders brought in by Rahul, while Navjot Singh Sidhu, who was backed by Rahul and Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, has been at loggerheads with Chief Minister Amarinder Singh.

Haryana leader Kuldeep Bishnoi—who tweeted that the leadership should have done more to convince Scindia to stay, and that many other leaders across the country were feeling alienated—is engaged in a tussle with Jat strongman Bhupinder Singh Hooda. Bishnoi, former Haryana chief minister Bhajan Lal’s son, apparently feels let down that the Congress did not support him when investigating agencies moved against him for alleged tax evasion. Bishnoi, it is learnt, wants his kin to get the lone Rajya Sabha seat that the Congress can win from the state.

Majority of the younger leaders in the party have been tight-lipped on Scindia’s move, adding credence to the view that they could also be weighing their options. “Rahul Gandhi should come back as party president as soon as possible, and take full command of the situation,” said Nirupam. “This is essential for the young leaders in the party getting due recognition.”

Following Scindia’s exit, Rahul replugged his old tweet announcing the nomination of Kamal Nath as chief minister. Quoting Leo Tolstoy, he had said, “The two most powerful warriors are patience and time.”

However, with many like Scindia fast running out of patience, it seems the time to act might have been yesterday.