On April 1, Kanishk Sable, 23, along with his mother and 70-year-old grandmother, was taken to Mumbai’s Kasturba Hospital for a 24-hour-observation, after his father, Namdev Sable, had tested positive for Covid-19. “It was a nightmare,” he says, recounting the moments over the phone. “First the shock following dad’s positive test result, and then, the fear of social exclusion. It was harrowing.”

Kanishk’s biggest fear was catching the infection from other suspected cases while they were inside the hospital, even if they did not actually carry the coronavirus from home. “Those 24 hours were the longest hours of our life,” he says. “We were 25 in all, all suspected for Covid-19, lying down in the same large hall. Our beds were at a distance of no more than one foot from each other. As we waited for our test results, we were offered tea and biscuits, and bland and flavourless meals comprising dal, rice, a dry-cooked vegetable and roti. All were sharing the same washroom, and people were getting together in a circle and chatting away.”

While Kanishk and his grandmother came out clean, his mother, Jayashree, tested positive.

Both his parents were taken to SevenHills Hospital for the treatment. “My parents got a fantastic treatment at SevenHills, where they had their own isolation rooms,” he says. “They were provided desserts, too, with meals. They spent most of their time resting and sleeping, and now they are back with us.”

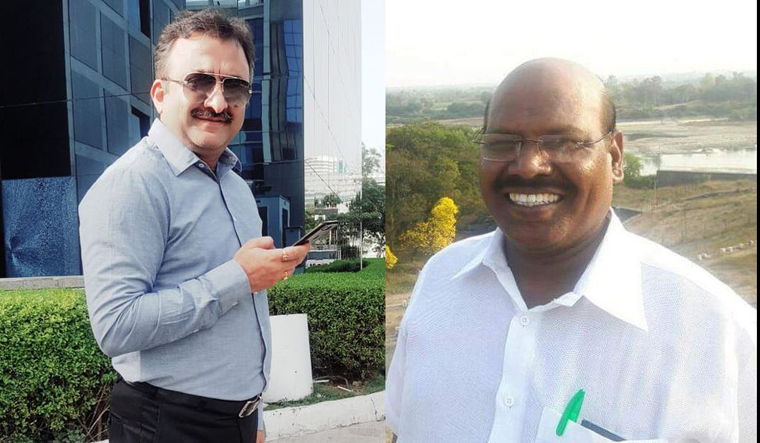

Meanwhile, Rohit Datta, who unwittingly became Delhi’s first Covid-19 positive case, spent 14 days of isolation washing his clothes, listening to spiritual music, connecting with friends and family over video calls and watching birds from the window of his room at Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital. “The loneliness combined with the feeling of guilt for putting others through inconvenience fills you up, and you get so emotionally overwhelmed that it starts to take a toll on the body,” explains Datta, who has recovered and is now back to managing his technical textile export business in Delhi.

The period of 14-day isolation which is a mandatory requirement for patients of Covid-19 can be torturous for many, and can lead to infrequent moments of nervous breakdowns even after the recovery, say experts. “With so much free time to ponder over things, it depends on what you do during that time and what your basic personality is like,” says Dr Sagar Mundada, a psychiatrist based in Mumbai.

The emotional distress is further exacerbated when the facilities for isolation are below par. “The public hospitals are overloaded and under-staffed, and isolation wards are not clean. Hygiene is a big issue during a pandemic,” says Kamayani Bali Mahabal, a health and human rights activist. “According to experiences of some in isolation ward, most of the public hospital staff are supportive, but they are constrained by the infrastructure of the hospital. This can potentially create a risk if the disease spreads rapidly, since medical staff will have to waste their time in managing people and dealing with infrastructural woes. In a private hospital, treatment in a general ward can cost you almost 011,000 a day; in an intensive care unit, it will cost approximately 050,000. For those who are positive, treatment might take 15 days. This adds up to an exorbitant 07.5 lakh per person in a super-specialty hospital. Hence, only those who are insured or are rich can access these.”

For Venkat Raghav, the first Covid-19 patient to recover from Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Chest Diseases, Bengaluru, it was relieving to know that he was Covid-positive, because he could at last attribute the restlessness and uneasiness that he was feeling to something. He had been feeling uneasy since his return from the United States in early March. In a YouTube video he posted recently, he lucidly describes his experience of being under isolation: “The facility was being developed to house a patient like me,” he says. “Windows were always open and the bed was creaking. [There was an air-conditioner, and the room] temperature was under 20 degrees Celsius, making it too chilly for me. The food was quite spicy. But in the next few days I was moved to a larger bed facility, which had a fan and where I could shut the windows if I wanted to. My fever would go up to 102 degrees [Fahrenheit] in early morning, and would be a constant 100 degrees [Fahrenheit] through the day. I was provided south Indian breakfast upon my request, and I was given antibiotics to prevent secondary infection. Because of jetlag, my sleep pattern was messed up. I was sleeping through the day and was completely awake at night. There were also days when I slept hungry even when I had fever. It took exactly two weeks for the fever to subside. The doctors really helped me navigate through this successfully.”

Another Covid-positive patient, Tomy Philip (name changed), was treated with erythromycin, Tamiflu and chloroquine in the isolation intensive care unit of Mumbai’s Fortis Hospital. Even after being discharged, he had been asked to continue home quarantine. He is strictly following the instructions. The family’s 1-BHK apartment has two separate toilets; Philip’s wife and son limit themselves to the living room and try to maintain as much distance as possible from Philip. The latter does feel the pinch at times, as if he is being “punished for a crime” he did not intentionally commit. “I get the food in the bedroom and do not go out at all,” he says. “This, of course, feels like I have been imprisoned, but then this, too, shall pass. The [officials of] Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation keep coming to check on me. Last time they stamped my hand before leaving. They have now locked down the entire building. Nobody is allowed to go out or come in. And, I feel as if I am responsible for all of this, but I am steeling myself against these thoughts.”