For want of a nail the shoe was lost,

For want of a shoe the horse was lost,

For want of a horse the knight was lost,

For want of a knight the battle was lost,

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

So a kingdom was lost—all for want of a nail.

The ancient rhyme rings true in South Block today. For want of a phone, 20 precious lives were lost.

For seven years, Indian and Chinese diplomats had been arguing over where to place a phone. Late last year they found a spot, but the ‘instrument’ has not yet been connected. It “is on the cards”, is what we heard last, in January, from Army chief General M.M. Naravane.

It is not an ordinary telephone, but a hotline between the armies of India and China. Had it been in place, perhaps the current military standoff in Ladakh could have been averted and the lives of 20-odd brave troopers of 16 Bihar, including its commander Colonel B. Santosh Babu, could have been saved.

The idea of a hotline, like the one between the military operations directorates of India and Pakistan, was agreed upon in the Sino-Indian border defence cooperation agreement of 2013, and reiterated during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Beijing visit in 2015. The Delhi-Islamabad line worked every Tuesday and on emergencies, and has averted several military mishaps on the line of control. However, the two sides could not decide where to place the China end. India wanted the line to run between the director general of military operations (DGMO) at the Army headquarters in Delhi and his counterpart in Beijing. But China wanted its end to be in Chengdu, at the headquarters of the People’s Liberation Army’s newly-formed western military command which looks after the entire border with India. Finally, India gave in. But before it could be installed, the Chinese moved into the Pangong lakeside and the Galwan valley in eastern Ladakh, with a never-before-made claim that the valley was theirs.

Now, many wonder whether hotline calls would be enough to sort out standoffs with the PLA, which has suddenly turned violent after four and half decades. “This changes the nature of the line of actual control [LAC] and the India-China relationship significantly,” said Jabin Jacob, associate professor of international relations, Shiv Nadar University. “For many years, Indian officials tried to downplay the seriousness of growing tensions along the LAC, saying there were protocols and agreements in place, and that there had been no casualties since 1975. The protocols were written at a time when infrastructure and technology were not as advanced as they are today.”

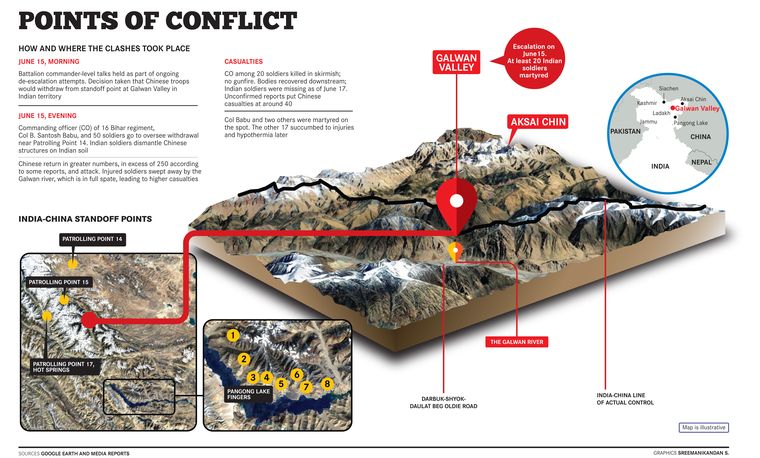

That China is no longer going by old protocols became clear on the evening of Monday, June 15, at Patrolling Point 14 in Galwan valley where Colonel Santosh Babu and his men were waiting, unarmed as per negotiated protocol, to ensure compliance of an agreement by which troops would disengage from patrolling points 14, 15 and 17 in Galwan valley and from Chushul and the north bank of Pangong lake. The Chinese troops in Galwan valley were to fall back 5km to the east, according to the disengagement plan agreed on June 6 between Lieutenant General Harinder Singh, commander of India’s Leh-based XIV Corps, and Major General Lin Liu, commander of China’s Xinjiang military district, at Chushul-Mondo border personnel meeting point. Around dusk, a group of Chinese soldiers armed with iron rods and construction tools (which they had brought for building structures in the intruded area) suddenly attacked Babu and his two aides who were standing at the front. As colleagues jumped to their rescue, they too were attacked, and soon it was a free-for-all. The brawl went on till midnight.

But, why did the formations in the rear not send reinforcements? “Our posts were on the other side of the stream, and they were unaware of what was happening,” said an officer. “Even if they knew, it would have taken some time for them to cross the stream and reach the spot. On the other hand, the Chinese just have to roll down their troops. So, it was like an ambush.”

The initial reports suggested that 20 were killed—some in the scuffle, a few by hypothermia, and a few fell off the cliff. Their bodies were recovered downstream from the Shyok river, into which the Galwan stream flows. The injured could be taken to the 303 Field Hospital in Tangtse and the Army Hospital in Leh only by morning.

Many in the Army headquarters now feel that senior officers in the defence and external affairs ministries should have overseen the disengagement plans, instead of leaving things to the on-scene commanders, especially since the Chinese had shown signs of violence even earlier. On May 5, the commanding officer of 11 Mahar was badly beaten up during a skirmish.

The Chinese have been making the intrusions unarmed. The pattern had been to send unarmed building parties into Indian territory or disputed territory and set up tents and other infrastructure. These intrusions were all supported by heavily armed formations which would be positioned on Chinese territory, but within clear view of the Indian formations and posts. Thus, the Chinese had moved a brigade-size force close to the LAC. India’s response had been to protest the intrusions and deploy forces mirroring the Chinese formations.

Intelligence analysts believe that India’s handling of the situation was far from coordinated. From the beginning, there was very little involvement of the foreign office. When two major-general level and eight rounds of lower-level meetings failed to defuse the tension, India asked for talks at corps commander level, which was unprecedented. The five-hour meeting, held on June 6 between Lt Gen Harinder Singh and Maj Gen Lin Liu, led to an understanding that both sides would de-induct forces from Patrolling Point 14 in Galwan valley to Patrolling Point 17, along with gradual de-escalation in depth areas. However, there was no conclusion to the talks over the Pangong lake intrusion, and, therefore, another corps commanders meeting was being planned when all hell broke loose in Galwan valley.

Senior Army officials say that while the LAC is neither delineated nor demarcated, the local formation commanders are clear about the ground alignment. “Our troops, wherever deployed, dominate each bit of it by patrolling and aerial surveillance,” said an officer at the headquarters who had served on the LAC. “Of course there are challenges of weather and terrain. We also have a reasonably good idea where Chinese perception of LAC runs on ground because we all observe them patrolling up to certain areas. This mutual understanding about LAC alignment on ground coupled with respect for protocols and agreements of 1993, 1996, 2005, 2012 and 2013 enabled peace and tranquillity so far.”

But the problem is that, as Jacob pointed out, “the subsequent updates to these protocols also predate the current phase of aggressive Chinese nationalism and assertiveness under Xi Jinping”. In fact, Xi’s China is not just reiterating old claims over territory, but also making new claims. What surprised India was that China had never made a political claim over Galwan, though it had coveted it militarily. Realising that it could dominate the entire neighbourhood from atop the hills around the valley, the Army occupied them in 1961. In the 1962 war, the Chinese dislodged the Indians, but unilaterally retreated after the war, realising that they could not maintain the post. India had reoccupied the heights and the valley but had been finding it hard to maintain them.

The completion of the road from Durbuk to Daulat Beg Oldie (near the LAC) and the building of a bridge across the Shyok have now changed the tactical picture. India can now maintain the Galwan heights and the neighbourhood of the LAC easily, by sending military supplies up the road. China worries that a well-supplied Indian Army may next be tempted to roll into Aksai Chin over which India has a claim.

Indeed, South Block had always known that building of the border roads and bridges would unnerve China. As External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, then as foreign secretary, told a parliamentary standing committee in October 2017, “as we build our border infrastructure, there will be a little bit of action-reaction where they are concerned”.

The scrapping of Article 370 of the Constitution and the reiteration of India’s claims made by politicians in Parliament over the Chinese-held Aksai Chin and the Pakistan-held regions of Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan also are believed to have provoked China into military action. As much was clear from the tweet made by Wang Xianfeng, the press officer in the Chinese embassy in Islamabad: “India’s actions of unilaterally changing the status quo of Kashmir and continuing to exacerbate regional tensions have posed a challenge to the sovereignty of China and Pakistan and made the India-Pakistan relations and China-India relations more complex.” The tweet was later deleted. All the same, as an Indian diplomat admitted, “the cumulative effect is that now China, too, has been drawn into the Kashmir dispute”.

As much is clear also from the Chinese move to bring in a new political factor into the LAC situation. It has now, for the first time, made a political claim over the Galwan valley, which it had occupied only for military purposes in 1962 and subsequently vacated. But in the May 5 intrusion, the PLA crossed its own claim line and made a political claim over territory up to the Galwan-Shyok confluence.

Now what? Naturally, the largest loss of life on the China frontier in half a century has put a question mark on whether India has the capability and the will. Comparisons will be made with Indira Gandhi’s robust response to the intrusion in Nathu La in 1967. “The response shattered the myth of Chinese invincibility,” said an officer. “We didn’t concede an inch then, and also gave them a bloody nose.” Then there was the Sumdorong Chu incident during Rajiv Gandhi’s reign when India showed signs of aggression and nearly went to war. The show of force led to Rajiv being invited to Beijing and the famous minute-long handshake with Deng Xiaoping.

Modi will have to live up not only to his combative reputation, but also to his two predecessors who had called the Chinese bluff even when they were militarily weaker. Right now, there is absolute caution reigning in the political circles. Unlike in the case of any incident involving Pakistan, which leads to political leaders and ministry spokesmen getting competitively outraged, there has been complete silence from the establishment. Finally, at a video meeting with chief ministers to discuss the Covid-19 situation, Modi assured “the nation that the sacrifice of our jawans will not be in vain,” and then called for an all-party meeting, which was another rare move on his part.

Lt Gen D.S. Hooda, former northern Army commander who supervised the 2016 surgical strike against Pakistan, however, ruled out similar action against China. “It can’t be something off the table,” he said. “We also must have plans to enter in some of their territory. We have the capability to strike.”

The recent accretions to the battle order, especially with the induction of tanks and armoured fighting vehicles, are signs of the Army’s enhanced self-confidence to hold against China in Ladakh where it had a disadvantage till recently. There are now three infantry brigades in eastern Ladakh, and a mechanised infantry battalion (equipped with armoured vehicles) and an armoured brigade with more than 100 recently inducted tanks. Since most machines behave oddly in the cold heights where air is thinner, new firing drills and protocols have been evolved and were proven in the exercises last September-October. The capability was announced, rather boldly, with the release of photos of the then northern Army commander Lt Gen Ranbir Singh sitting atop a T-90 tank and watching the exercises.

All the same, currently the attempt on the border is to defuse the situation. With passions running high in the battalions that were involved in the clash, they are “likely to be replaced so as to prevent any untoward actions,” said an officer. Though the opposition has been restrained, public anger could be simmering. “Public tempers can complicate matters for policy makers,” said Harsh Pant, head of Observer Research Foundation’s strategic studies programme, explaining why India should try for a “de-escalation quickly”.

However, the loss of life would remain a slap on the Modi government’s face unless it is avenged, especially since the Army has been contending that it has the capacity to stand up to the Chinese. “The Indian Army is not a pushover,” said Lt Gen Anil Ahuja, who had commanded the 5 Mountain Division in Tawang and the 4 Corps which holds against China. “On the nearly 4,000km long boundary with China, there are places where we can give them a befitting response. Letting China off the hook this time would contribute to upsetting the regional balance of power perception.”

Coupled with that is the perception that India’s neighbourhood policy is in a shambles. With even puny Nepal, which had been beholden to India for two centuries since the Anglo-Gorkha wars of the early 19th century, cocking a cartographic snook, perhaps it is time to follow what Teddy Roosevelt said a century ago: “Speak softly and carry a big stick.”

With Mandira Nayar and Namrata Biji Ahuja