When Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014, many in China saw him as a man of development who had, as Gujarat chief minister, travelled to their land looking for investment. Policymakers in China had then told their president, Xi Jinping, who had taken office in 2013: “This Indian prime minister is a resolute leader with remarkable charisma. Frugal, clean and effective on social media, he looks like a saint, combining tradition and modernity.” It seemed like a time for change, and Xi was keen on India joining his One Belt One Road project, now known as the Belt and Road Initiative. It sought to connect China with Europe by road and sea, and South Asia through a Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor. Though India declined to join the BRI, the friendship between Modi and Xi seemed unaffected. But now the two countries are in conflict, with their soldiers massacring each other in June, the bloodiest violence in more than four decades. Though all-powerful—he is the president of the country, the general secretary of the Communist Party, and the chairman of the Central Military Commission—Xi is not above criticism in China. His decisions are debated and questioned in the Politburo and the Central Committee. He is now under pressure, as it was he who had sold the BRI idea to the party. The onus is on him to make it a reality, and India’s resistance does not suit him.

While China grew massively in the past three decades, its western part remained mostly backward and inaccessible. This is the part that borders India. So, under Xi, China decided to connect the southwestern Yunnan province to the autonomous Xinjiang province in the northwest through roads and airports. In the past few years, Xinjiang has also seen rampant militarisation, worrying India. Modi has also been building roads in the northeast part of India, which borders China. This activity increased after Article 370 was revoked and Ladakh was made a Union territory last August. Most Indians, obsessed with the Pakistan border, did not notice that there were more than 400 transgressions by the People’s Liberation Army on the India-China border in 2017. They woke up only when the Doklam standoff happened that year. In this dispute, India objected to China building a road in Bhutan to further its BRI project. Confidence-building measures followed talks between the two armies. The Eastern Command monitored the measures in the northeast and the Northern Command monitored them in Ladakh. “[Regardless,] China is building huge physical infrastructure in Bhutan at the request of the people of Bhutan, who would like to come out of poverty,” a Chinese strategist told THE WEEK.

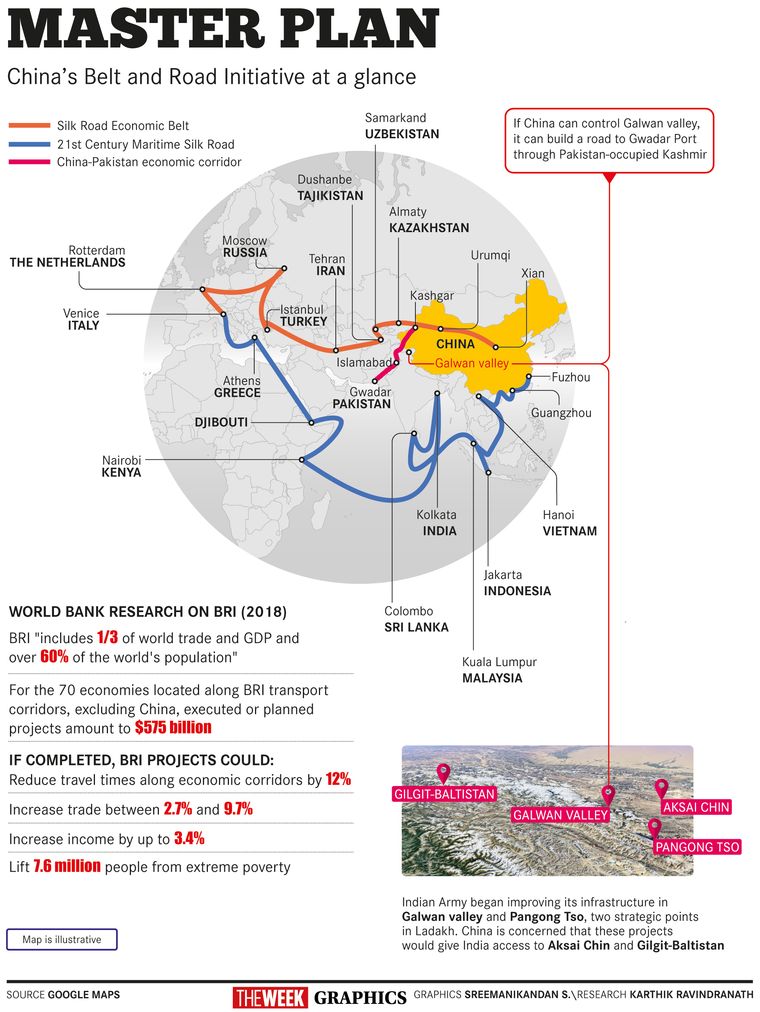

As China built up Xinjiang, the Indian Army started building roads in the Galwan valley and near Pangong Tso, two strategic points in Ladakh. China sees it as India’s effort to gain access to Aksai Chin and Gilgit-Baltistan. The Chinese were also angered by statements of Indian politicians, including a cabinet minister, that India would take back Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Aksai Chin. The Chinese State Council, the country’s highest administrative authority, seem to have taken these statements at face value. Responding to THE WEEK, it called the Modi government the “aggressor” and accused India of trying to repeat another Doklam in Ladakh. “It is the result of New Delhi’s miscalculation and the new ‘forward policy’ of the BJP government,” Li Xiaojun, information director at the State Council, told THE WEEK. “New Delhi is clear where the LAC is and it has ordered the soldiers to take wrong steps into the Chinese fields, like it did in Doklam.” Apparently, the statements by Indian leaders irked China so much that Xi asked the PLA to take full control of the Galwan valley and Pangong Tso, which China says were “unmarked and disputed”. “China tried to take control of the Galwan valley because that would enable it to create a parallel CPEC (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) road through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir,” said Major General K.K. Ganguly, a veteran who fought in the three wars between 1962 and 1971. He said Xi had been sidelined internationally because of the Covid-19 pandemic and had received threats of an investigation into the outbreak. “He asked for India’s help (to open up India for Chinese companies) and our prime minister turned a blind eye,” said Ganguly. “The prime minister also checked Chinese investment in sectors that are now open to domestic players only. As a result, China [executed] an inhuman massacre at the border.”

The current dispute is not confined to Ladakh. The two armies also fought at the Naku-La sector in north Sikkim in May. Apparently, China wanted not only to redraw the Ladakh border but also to revoke its recognition of Sikkim as Indian territory. “If the Chinese were shouting that Sikkim is not Indian territory, then too, we have a problem,” said Jabin Thomas Jacob, associate professor, department of international relations and governance studies, Shiv Nadar University. “[China] had officially accepted that Sikkim was Indian territory in 2003.” He said the Chinese were determined, unlike during Doklam, to set a new status quo. “This time, the transgressions are of a different nature for two reasons. First, they intruded in Galwan, across an alignment of the LAC that was previously not disputed. Second, they are preventing Indians from patrolling up to our perception of the LAC at Finger 8 at Pangong Tso and have blocked us at Finger 4, which is their perception of the LAC. In both instances, this is a change of the status quo. Why now? Why not now? It was always in the cards post-Doklam.” Jacob agreed that the clashes reflected China’s desperation to implement the BRI. “China would do whatever it takes to implement the BRI successfully,” he said.

In May, when scuffles started in Ladakh, the State Council told THE WEEK: “[The issue] is a nonstarter here. We are busy with parliament proceedings (Hong Kong-related legislation). Nobody cares and India plays it up too much.” Apparently, unlike during Doklam, Xi did not lay the groundwork for diplomatic dialogue this time. He left it to the military to resolve the matter. As a result, Modi’s Doklam team, led by National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, has been missing from the headlines. Li said the recent meetings at the joint secretary and military levels were a big sacrifice on China’s part. “Compromise means give and take,” he said. “No winner and loser. But India just overlooked the compromise we made.” The talks failed and clashes began. On June 16, India lost 20 soldiers; a week later China admitted that it had lost less than 20 soldiers.

India had about 10,000 troops against China’s 7,000 in Ladakh. But China flew in 10,000 more from Wuhan before the corps commander-level talks on June 6. Indian Army sources said China even brought fighter planes to Xinjiang airstrips. “[It was] tragic and unfortunate. It was an unexpected loss of precious lives [on both sides],” said Li. He said India had broken the resolution agreed upon on June 6; it did not stop the construction of roads and tried to obstruct China miles away. “India should stop living in a dream on border issues,” he said. “China would never retreat 20km only to find India taking them all and edging forward.” “It was almost impossible for China to convince the Indian authorities and people about the intricacies of [the] border,” the State Council said to THE WEEK in a statement. “But we tried to do that impossible work thanks to our strong leadership. But India broke its word in the end.” The State Council alleged that a section of the Indian media had “instigated the government”. Calling the border situation “very dangerous”, it said, “We would like to see political and military leaders in India as well as the Indian media stop adding fuel to the fire. Both sides should strictly observe the political documents [agreed to] in the past on border tranquillity in letter and spirit.” Asked to comment on foreign ministry spokesperson Anurag Srivastava’s statement that China’s claim on the Galwan valley was untenable and exaggerated, Li said: “Mr Srivastava used similar terms like our side. But his LAC is not our LAC. His fruit might mean mango, but ours might mean apple. This kind of difference can only be solved through words and pens, instead of fists and stones.” A Chinese official alleged that the Indian soldiers had thrown the first punch in both Sikkim and Ladakh. “Seeing the brutality of the Indian force, we had to retaliate,” said the official. “It was unfortunate, but the instigation was clearly from the Indian side.”

Ironically, India and China were planning to celebrate 70 years of their diplomatic relationship in 2020. Modi and Xi discussed it when they met last year and decided to choose a suitable time for the celebration. In fact, they planned to visit each other as a mark of gratitude. “The face-off is a slap to both leaders,” said Li. “It should have been avoided or [should] at least be resolved without further escalation. Otherwise, the 70th [anniversary] events would turn out to be useless and emotions on both sides [would be] damaged beyond [repair].” The recent clashes have also drawn attention to other parts of the India-China border, especially in Arunachal Pradesh, which China sees as part of South Tibet. Major General Ganguly said it was a matter of time before there was a flare-up on the eastern border.

“China is an expansionist force,” he said. “Look what it has done in the South China Sea. I am sure it would create a complex situation in Arunachal Pradesh. But I am sure the people of Arunachal Pradesh would checkmate it.”

Only two dozen of 400 border transgressions in 2018 were in Arunachal Pradesh; the majority were on the northern border, said Army sources. So, is the Arunachal Pradesh issue settled? “No, I do not think so,” said Jacob. “Such transgressions and face-offs also happen in Arunachal. It is only a matter of time before something serious happens there, too.” Li said the boundary dispute was a colonial legacy; British India had annexed thousands of kilometres of Chinese territory. “Independent India happily inherited the map, invaded Tawang in 1950 and seized South Tibet,” he said. “The Johnson Line and others were only dreamed lines. The ground reality and historical reality were quite different. Aksai Chin was never under British India’s rule. The Indian people should know this. They should also know the internal report on the 1962 border war.” The report is classified in India, but sources said it talked about how India was politically “defeated by China”, which led to military backtracking. However, the situation has changed a lot in the past six decades and India has strengthened the Arunachal Pradesh border with huge military build-up. It has also influenced the people of Arunachal Pradesh culturally, trying to instil in them a feeling of Indianness. And perhaps China realises that Arunachal Pradesh is not a desert, like many parts in Ladakh, and it would be difficult to be similarly aggressive there. In fact, Li said, “For the Chinese, it would be better to accept the reality that it is almost impossible to take back each inch of its former territories, namely some parts of South Tibet.” However, by positioning itself in Ladakh firmly, China has challenged India’s position in South Asia. Even India’s friends, such as Bangladesh, could be left with no option but to accept the Belt and Road Initiative, even if they face the possibility of being debt-trapped. “At the moment, it does not look like the Chinese are going to withdraw from Pangong Tso,” said Jacob. “They have achieved what they wanted. They seem to think they have the strength to change the status quo and get away with it.” The Modi government would either have to retaliate on the border or defeat China diplomatically on the international stage. India has begun to consolidate the border with more troops, arms and ammunition, and fighter jets. Major General Ganguly, however, said, “India would have to [consider] all other avenues apart from military options. The entire world economy [has gone] haywire after Covid-19. The Chinese economy is not that hurt. A war would make things complex. India must think how, by aligning with world powers, it could cause major harm to the Chinese economy and further isolate it from the world.” Prime Minister Modi is at a crossroads. With Covid-19 spreading faster, experts said, it would be prudent not to choose military options. As for reaching out to other nations, some analysts felt Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has partnered with China for the BRI, could be a better option than US president Donald Trump, who is already in a verbal war with China. A Russian intervention could hold the Chinese army back with no further bloodshed. Modi, they said, was unlikely to cede an inch on the BRI in exchange for withdrawal of Chinese troops. Li finds India’s objections ridiculous. “China advocates the five principles of peaceful coexistence, good neighbourly relationships, [and] win-win cooperation. The top priority is to eradicate abject poverty and build a comparatively well-defined society (through BRI).” Modi would, of course, love to eradicate poverty, just not the Chinese way.

As David Chang, an industrialist in Shanghai, said, “From 2019 to 2020, within a mere eight months, the Sino-Indian relationship has gone from holding hands to fist fights. The Asian century, which is centred on cooperation between the two most populous countries, is now entering an unpleasant new normal.”