Uddhav Thackeray did not have any inkling of what was to unfold when he logged onto an online meeting on June 15. The Maharashtra chief minister presided over the signing of deals with three Chinese firms—Great Wall Motor Company, Hengli Engineering and PMI Electro Mobility Solutions’ joint venture with Photon. The three agreements totalling around Rs5,000 crore of investment were part of Thackeray’s ambitious plan to reinvigorate the state’s Covid-19-ravaged economy. In a few hours, however, everything changed.

As the brutal killing of 20 Indian Army men in a skirmish in Galwan valley on the India-China Line of Actual Control (LAC) sent shockwaves across the country, popular sentiment rose up against Chinese products and businesses. Calls to boycott Chinese products began trending on social media and protest marches were taken out in many cities.

Some people in Gujarat threw out their made-in-China televisions and stomped on them, while traders in Delhi made a ‘Holi’ bonfire of Chinese products. The Uttar Pradesh government had to deploy policemen outside the factories of Chinese firms in Greater Noida and an apartment complex where some 100 Chinese nationals live. Chinese phone makers in India suddenly started highlighting their ‘Indian’ credentials, and startups with Chinese funding started referring to themselves as “proudly Indian”. In the frenzy, Thackeray’s dream projects did not stand a chance, and were put on hold.

The Centre also wasted no time. One of the first deals to be axed was the Indian Railways’ Rs471-crore signalling work on the Kanpur-DDU line awarded to Beijing National Railway Research. State-run telecom operators BSNL and MTNL were asked to drop Chinese vendors. E-commerce bidders have been asked to specify ‘country of origin’ while listing on the commerce ministry’s e-marketplace, with the provision likely to be extended to e-commerce sites like Amazon and Flipkart.

India had already fired the first shot back in April, when it stopped the automatic foreign direct investment (FDI) route for investment from neighbouring countries. The worry then was that Chinese investors may take over Indian firms weakened by the pandemic. It was followed in May by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call for ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ and ‘Vocal For Local’, which actually meant ‘stop depending on China and build self-reliance in manufacturing’.

Post Galwan, the gloves are off. New Delhi’s move, riding on the coattails of the backlash on the streets and in drawing rooms against China’s ‘aggression’, may no longer limit itself to piecemeal gestures. The department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) has asked industry bodies to submit lists of Chinese imports by Indian companies—the aim is to chart out an action plan to replace non-essential imports with local products where possible. Rules for government contracts, both Central and state, are also set to be tweaked based on quality and technical specifications so that Chinese companies do not become eligible. Further tightening of FDI rules to keep out future Chinese investments now appear likely. There is now an added urgency to take a re-look at India’s Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with countries like Thailand and Vietnam to plug the loophole of Chinese products taking this ‘third party’ route to enter India.

“Economic boycott has been used effectively by this government recently in the cases of Malaysia and Turkey. In both these cases, India had an upper hand,” said Divakar Vijayasarathy, managing partner of the business advisory firm DVS. But he advocates caution with China. “India is dependent on China for many critical supplies. Any large-scale attempt to boycott Chinese products would invite an export restriction of these critical products. Hence, economic warfare has to be meticulously planned and we should be prepared for a backlash.”

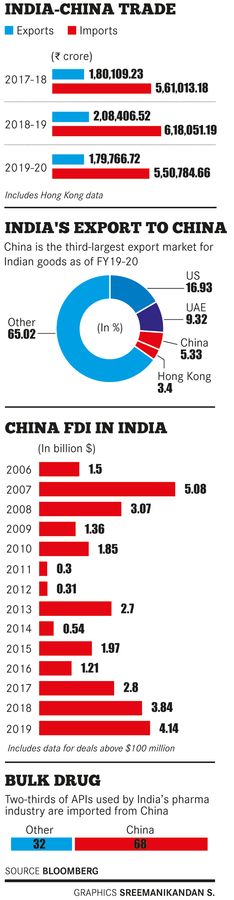

Breakups are never easy. According to Invest India, the national investment promotion and facilitation agency, India-China trade, which was worth just $2.8 billion in 2001, has grown 31 times to $87 billion in 2018-19. While India’s exports to China have grown 12 times to $16.8 billion during this period, imports from China have jumped 45 times, to $70.3 billion.

China is well entrenched in India’s startup and technology ecosystem. In fact, Chinese tech giants and venture capital funds are the primarily vehicle for investments in tech startups. Over the past five years, companies like Alibaba, Tencent, Didi Chuxing and Fosun International have invested an estimated $4 billion in Indian startups. Of the 30 Indian unicorns (startups valued at $1 billion or more), 18 are Chinese funded. Marquee names like Paytm, Oyo, MakeMyTrip, Delhivery and Byju’s have received funding from China.

A bigger presence are the many Chinese apps with huge followers in India. It is estimated that half of top app downloads (iOS and Android combined) in India in 2018 were those with Chinese investments, such as UC Browser, SHAREit, TikTok, and Vigo Video.

The thriving Indian pharmaceutical industry is heavily dependent on critical components from China. Over the past three years, 68 per cent of the active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) used in medicines in India were imported from China. These API supplies were hit hard as Chinese factories were forced to shut down by the Covid-19 pandemic in January and February. If the imports of API from China were to be crippled, it would have a huge impact on the $40 billion pharma industry, which is one of India’s largest exporters. “If China is taken off the equation immediately, the supply chain would be severely affected, with closures for a long time,” said Debabrata Chakravorty, president (global supply chain, sourcing & contract manufacturing) of the pharma major Lupin. “There are limited immediate alternatives globally, even at a higher cost.”

It is a similar case with the automobile industry. According to credit ratings agency ICRA, China accounts for 27 per cent of India’s auto component imports. India also imported capital goods worth around $12.78 billion and electronics worth $18 billion from China from March 2019 to February 2020.

“There is a trade relationship that has developed over the last 20-40 years between China and the rest of the world,” said Amit Bhandari, a fellow at geopolitical think tank Gateway House. “If something has developed over such a long period, you cannot unwind it in one week, two weeks or even a year. It is a long-term process.”

Chinese companies have cumulatively invested more than 06 lakh crore in India, spawning 1.87 lakh jobs in the last two decades or so. They have been scaling up in recent years on the value chain. Besides telecom and software, Chinese companies in sunrise sectors like electric vehicles and renewable energy have been setting up major projects in India.

Almost half of the consumer durables imported into India are Chinese. About 40 per cent of leather products come from China. While that shirt or trouser you are wearing may be made in India or Bangladesh, chances are that the buttons and zippers came from China.

The reason everywhere is the same. The cost. For instance, half of the smart TVs in India are Chinese. The alternatives, those from Japan or Korea, could cost 20 to 45 per cent more. The pandemic also, ironically, helped the Chinese cause. “It has reduced the purchasing power of the Indian public as they have less money in hand,” said Anusree Paul, trade economist & associate professor, School of Management, BML Munjal University. “Indian companies are not equipped to substitute China’s cheaper products.”

Everyone, however, agrees that India should focus on developing the domestic industry, which would help it naturally compete. “Currently, 40 per cent of India’s imports are products like electronic items and medical instruments. And almost 50 per cent of imports from China are either in capital goods or intermediary goods, which form crucial supplies to the domestic industry. What can be done is to reduce low-grade imports from China and produce such items domestically,” said Mohit Singla, chairman of the Trade Promotion Council of India.

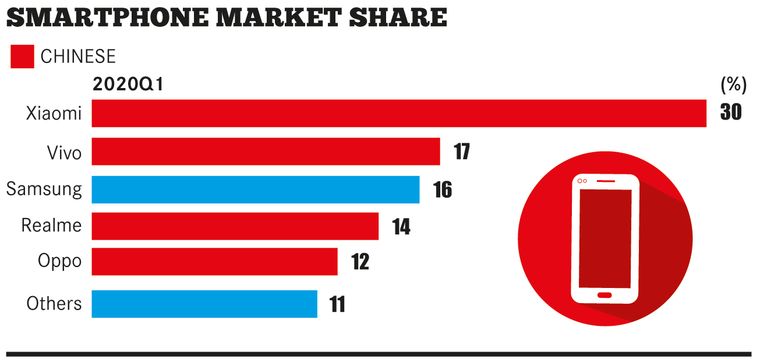

Indian brands account for just one per cent of the booming domestic mobile phone market. “A person does not go to the market and look for products made in China. Instead, he looks for high quality products that are affordable. Chinese products have cracked that equation,” said brand expert Harish Bijoor.

That is why consumers giving up Chinese products en masse is an unlikely scenario. “Chinese products are value-for-money and they have made their mark in India,” said Prachir Singh, senior research analyst with the telecom consultancy Counterpoint Research. He does not see much merit in the campaign against Chinese companies. “Components from China and other parts of the world are assembled in Indian factories that employ thousands of Indians to bring out a Chinese brand mobile phone. How can you label it Chinese in this globalised environment? Like it or not, they are delivering value to the Indian GDP as well,” he said.

Let alone its logicality in a post-global world, any attempt by the Indian tiger to leap out of the dragon’s chokehold may not be practical or sensible. “India still does not have adequate infrastructure and alternative investment prospects to substitute China,” said Paul. “So India is going to be affected more if it takes any stringent decision based on the present bellicose sentiments.”

So, what is the way out?

Sankar Chakraborti, CEO of Acuite Ratings, said India could afford to reduce the dependency on China in a phased manner. “We believe that Indian industry has the wherewithal to safeguard its interests,” he said. According to Acuite, without any significant additional investments, the domestic manufacturing sector can substitute 25 per cent of the total imports from some specified sectors in the first phase, thereby reducing $8.4 billion in trade deficit in a year. “With a strategic intent and highly calibrated approach from both the government and industry, the Indian economy can see a new narrative that can not only reduce its trade deficit but also kickstart a cycle of fresh private sector investments,” said Chakraborti.

The government seems to have a plan. Prime Minister Modi met key ministers like Piyush Goyal and Nitin Gadkari a week ago along with officials. Presentations were made on how to improve India’s ease of doing business and ramp up manufacturing and exports. An interesting idea that gained traction was making states compete with each other to attract investment.

Another meeting of ministers with industry captains took inputs on how to reduce turnaround time at ports and how infrastructure can be improved in the countryside, a crucial determinant in making India an attractive hub for manufacturing. Among the non-fiscal measures being discussed are labour, ease of doing business and coordinating the efforts of the Centre and states in a bid to attract more investment. The writing on the wall for the Indian tiger is clear—crouch, crawl and create your own space in the long run, but it will be hard to ignore the dragon in the room right now.